Dorchester's Blue Hill Avenue

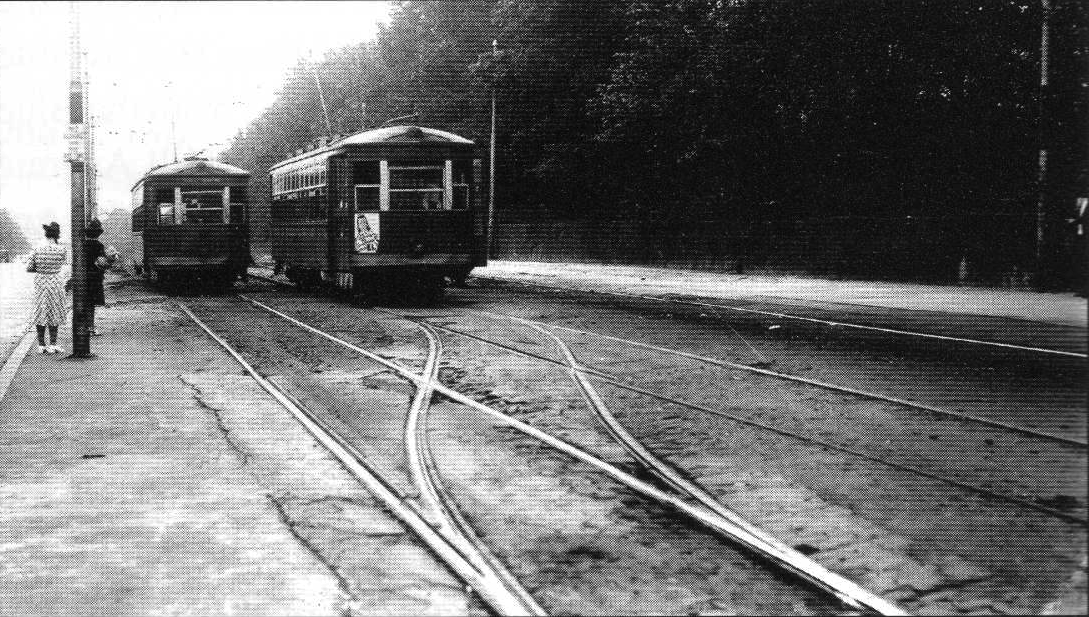

Type Five streetcar making its way up Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester away from Mattapan Square and towards Franklin Park along the streetcar median for the venerable 29/Mattapan-Egelston streetcar route, on which this Type Five is operating. This picture was taken in 1955; a few months later, this line will be replaced by buses and the tracks will be removed to allow more space for car travel.

Same location (Blue Hill Avenue by Donald Road) today. The streetcar median has been removed, and accordingly there is an extra travel lane for cars in each direction. Image copyright Google Maps.

This article is dedicated to examining the evolution of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester. Blue Hill Avenue is a four-mile-long street stretching from Dudley Street in Roxbury through Roxbury, Dorchester and Mattapan to end in Mattapan Square. This article will focus upon the section of Blue Hill Avenue that passes through Dorchester, located between Seaver Street and Morton Street. In addition to focusing upon changes in transit in the area, this article will also be dedicated to elucidating the remnants of the once-significant Jewish presence along Blue Hill Avenue, which was centered in our area of focus.

Introduction

From a scarcely populated region primarily composed of farms and estates to one densely packed with multi-family dwellings, Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester has undergone radical change from the late 19th century until today. Like much of Boston, the development of Dorchester was driven significantly by the construction of transit lines in the area. The influence transit had upon Dorchester in particular is especially noteworthy, as all parts of Dorchester, unlike in neighborhoods such as Brookline, the South End or Lower Roxbury, are located between four and eight miles away from downtown Boston, making walking, or even traveling via horse, very impractical.

The rapid pace of transit-oriented development in Dorchester becomes evident when passing along Blue Hill Avenue, which has always been one of the neighborhood's main thoroughfares. As trolleys began to run along Blue Hill Avenue, land that was once occupied by expansive fields and was considered out of the way of the action in Downtown Boston was suddenly prime space for development. Accordingly, within a span of twenty-five years between the late 19th century and early 20th century, Blue Hill Avenue went from being a rural country thoroughfare connecting farmland to downtown Boston to a busy strip of apartment buildings and businesses and a prime destination in Boston.

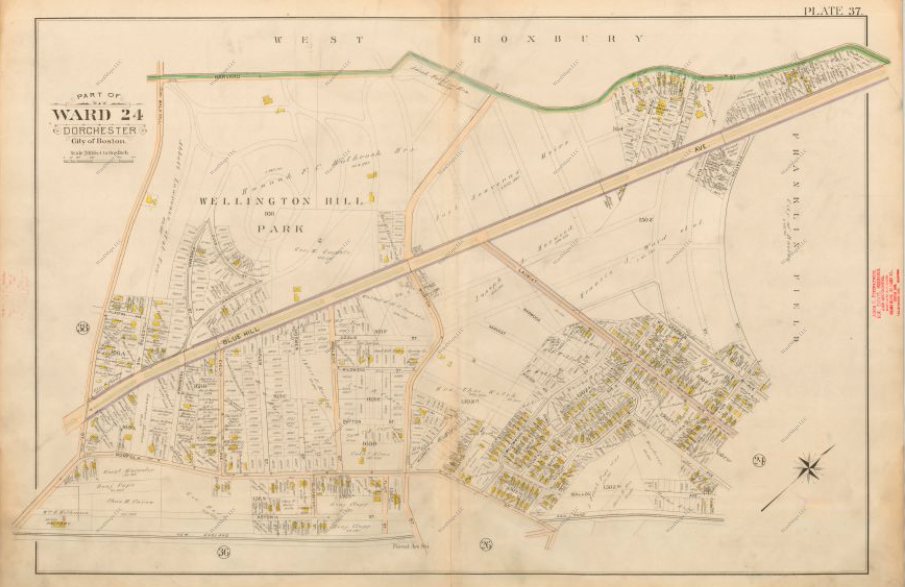

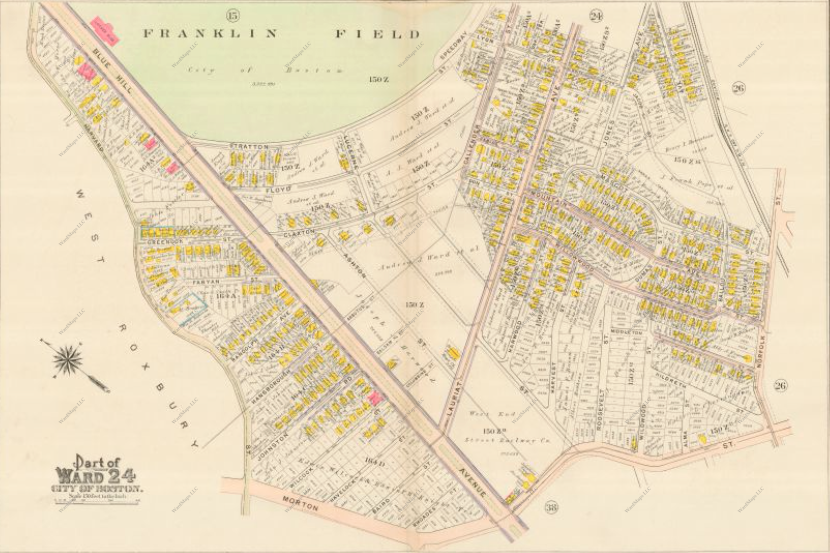

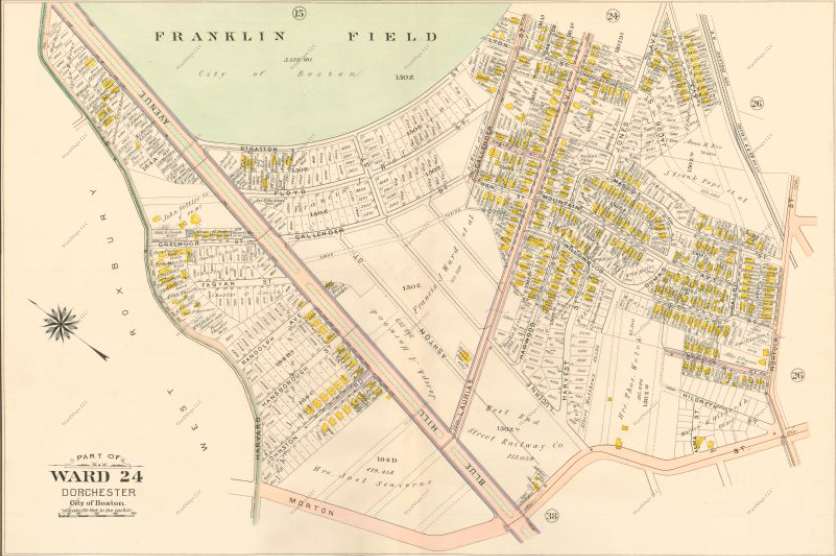

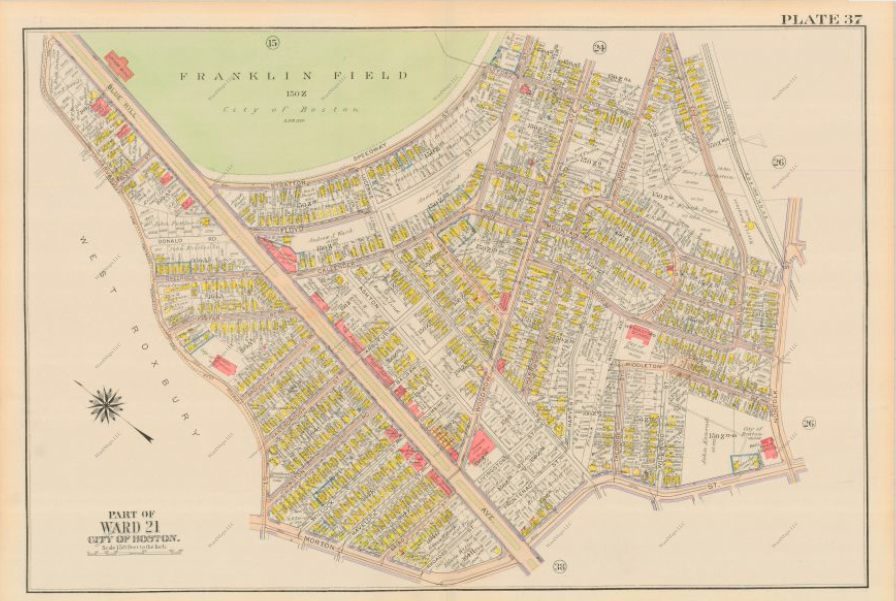

Streetcars: The Catalysts of Blue Hill Avenue's Development

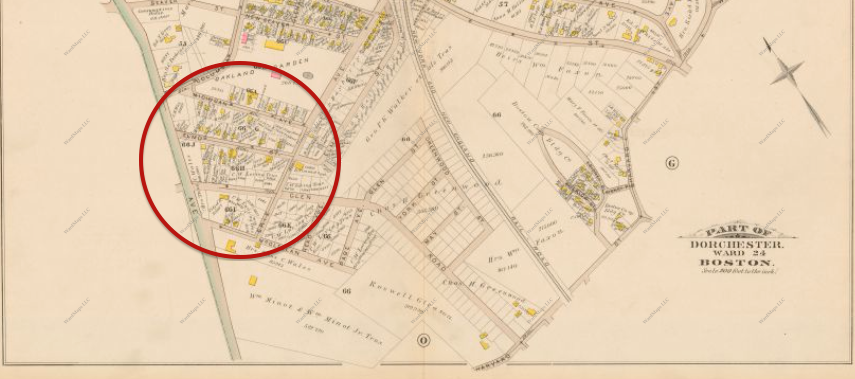

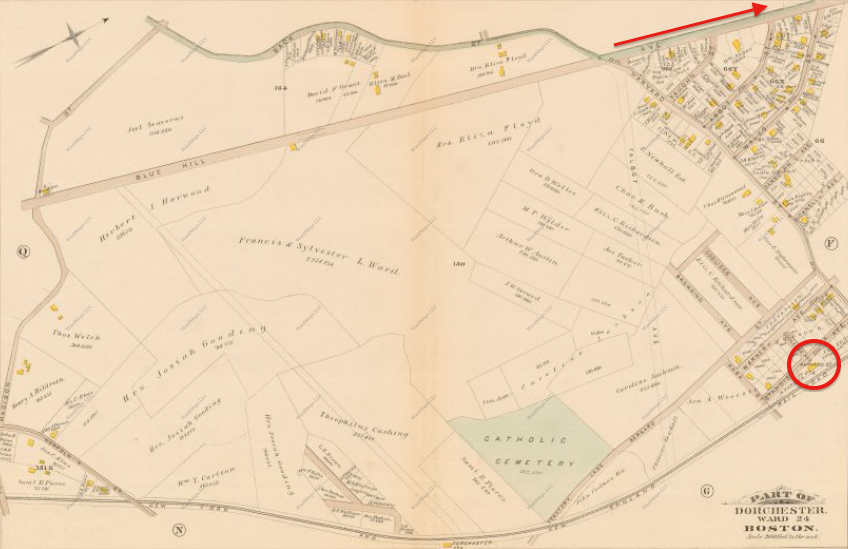

Above are two 1884 Bromley maps of the area just south of the Blue Hill Avenue-Seaver Street intersection. The first shows the area from Seaver Street to Harvard Street, and the second shows the area south of Harvard Street with Franklin Park to the left. Right now, the area surrounding Blue Hill Avenue is almost completely undeveloped; vacant fields line the road. Electric streetcars have not yet arrived in Boston; however, there are passenger trains and horsecar routes that run through Dorchester and stop or terminate in close proximity to the area. The closest horsecar route runs along Blue Hill Avenue to terminate just by Franklin Park; the streets via which the horsecar looped are circled in dark red in the top map and annotated with a red arrow in the bottom map. In addition to horsecar service, there is also a New York and New England Railroad (assumed by New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad in 1898) passenger train station (Harvard Street Station) nearby, circled in red on the bottom map.

Already in the 1880s, Dorchester was considered an attractive destination by many Bostonians. Compared to downtown Boston, Dorchester was like the country. Nearby Roxbury was originally called "Boston Highlands," emphasizing the country nature of these future "streetcar suburbs." Accordingly, Dorchester and Roxbury held lots of potential for exploration and discovery for the adventurous Bostonian. Boston Illustrated, an 1870s-1880s Boston tour book, states that "among the favorite [horsecar] routes are those leading to Grove Hall, Franklin Park, and the Dorchester District, a distance of about five miles [from downtown], requiring nearly an hour for the outward trip, which costs only five cents." Nowadays, it can take an hour to reach the Wachusett Mountain ski area in Western Massachusetts by car! To 1880s Bostonians, Dorchester was the equivalent of Western Massachusetts to Bostonians nowadays, a frontier just waiting to be explored. (Read the selection of Boston Illustrated where the above quote is mentioned here.)

Such exploration was made possible by one of the earliest forms of urban public transit—the horsecar. Below is an 1885 West End Street Railway map that shows the old horsecar loop, circled in red, that was used to turn horsecars that terminated at Franklin Park around so they could continue back towards downtown Boston. Look to the right of the red circle, and you will see that there was also a horsecar line that ran down Washington Street in Dorchester to terminate in Codman Square that would have provided convenient service to the area east of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester and to those pioneers who took residence there in the 1880s.

Already in the 1880s, Dorchester was considered an attractive destination by many Bostonians. Compared to downtown Boston, Dorchester was like the country. Nearby Roxbury was originally called "Boston Highlands," emphasizing the country nature of these future "streetcar suburbs." Accordingly, Dorchester and Roxbury held lots of potential for exploration and discovery for the adventurous Bostonian. Boston Illustrated, an 1870s-1880s Boston tour book, states that "among the favorite [horsecar] routes are those leading to Grove Hall, Franklin Park, and the Dorchester District, a distance of about five miles [from downtown], requiring nearly an hour for the outward trip, which costs only five cents." Nowadays, it can take an hour to reach the Wachusett Mountain ski area in Western Massachusetts by car! To 1880s Bostonians, Dorchester was the equivalent of Western Massachusetts to Bostonians nowadays, a frontier just waiting to be explored. (Read the selection of Boston Illustrated where the above quote is mentioned here.)

Such exploration was made possible by one of the earliest forms of urban public transit—the horsecar. Below is an 1885 West End Street Railway map that shows the old horsecar loop, circled in red, that was used to turn horsecars that terminated at Franklin Park around so they could continue back towards downtown Boston. Look to the right of the red circle, and you will see that there was also a horsecar line that ran down Washington Street in Dorchester to terminate in Codman Square that would have provided convenient service to the area east of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester and to those pioneers who took residence there in the 1880s.

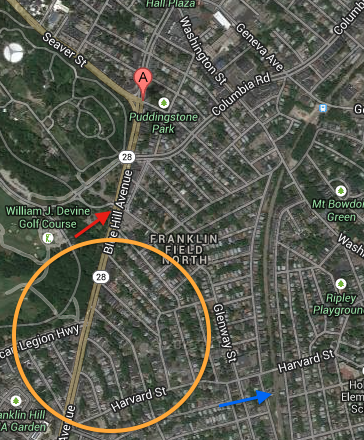

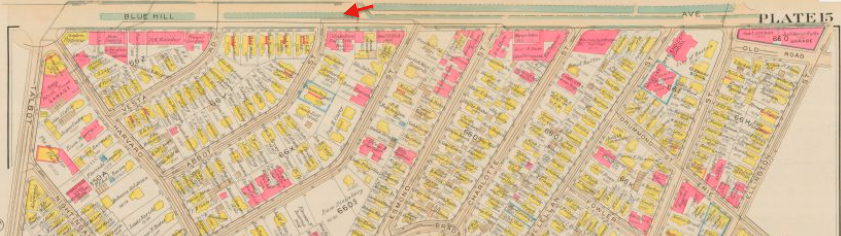

To better orient you as to the locations of the locations of the landmarks I have described above, I have included an annotated modern-day Google Map of the area below:

Circled in orange is the area shown in the 1884 Bromley map shown earlier. The blue arrow points to Harvard Street Station, and the red arrow points to the former location of the horsecar loop by Franklin Park on Blue Hill Avenue.

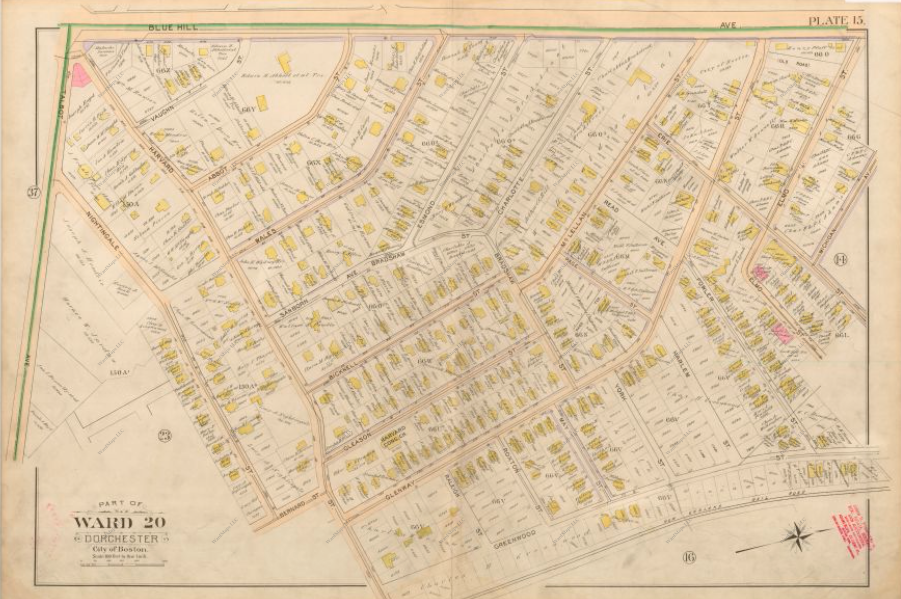

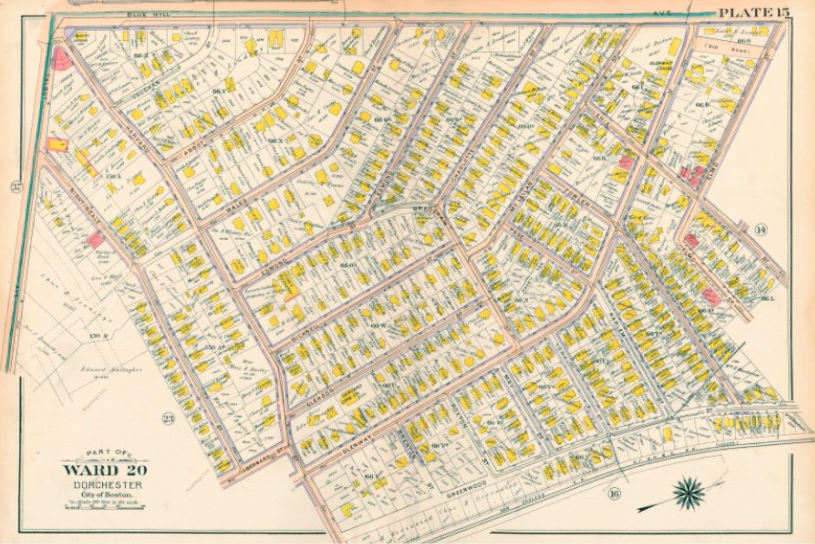

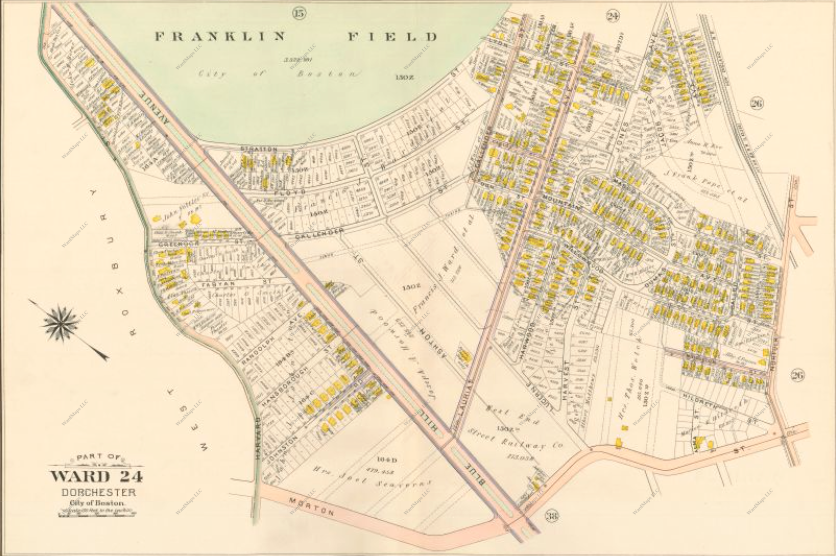

By 1898, as shown by the Bromley maps below, considerable development had taken place along Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester. The top Bromley map shows the area between Franklin Field (just south of Harvard Street) extending north almost to Seaver Street, where there are many more houses built now than in 1884, and the bottom Bromley map shows the area between Franklin Field and Wellington Hill (slightly south of Morton Street into Mattapan), where there has been less, but still some, development. Almost none of the brick storefronts that will line Blue Hill Avenue later have been built, though there are clearly many wooden two-family homes and triple-deckers. (Note: on a Bromley map, for fire insurance purposes, a building built from wood is marked in yellow and a building built from brick is marked in pink.)

Franklin Field-Seaver Street in 1898.

Wellington Hill-Franklin Field in 1898.

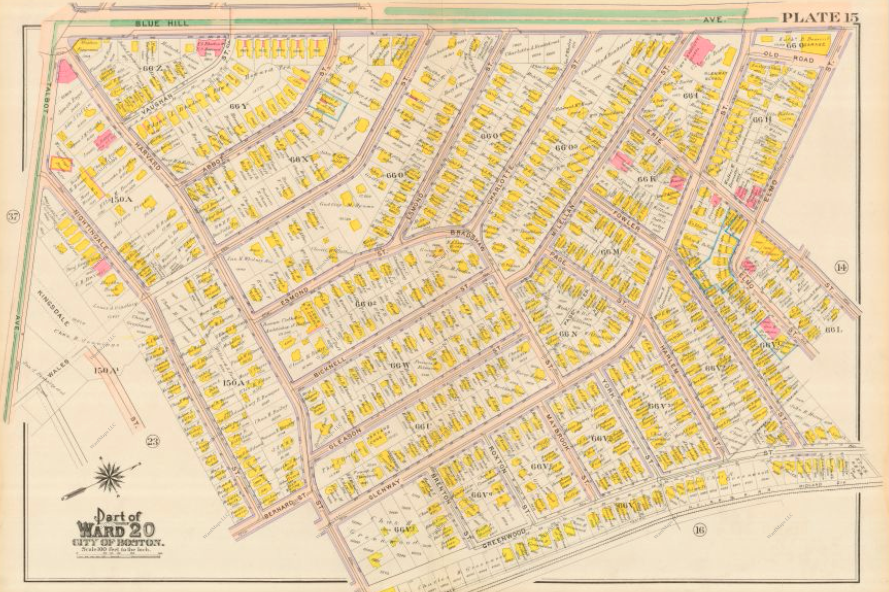

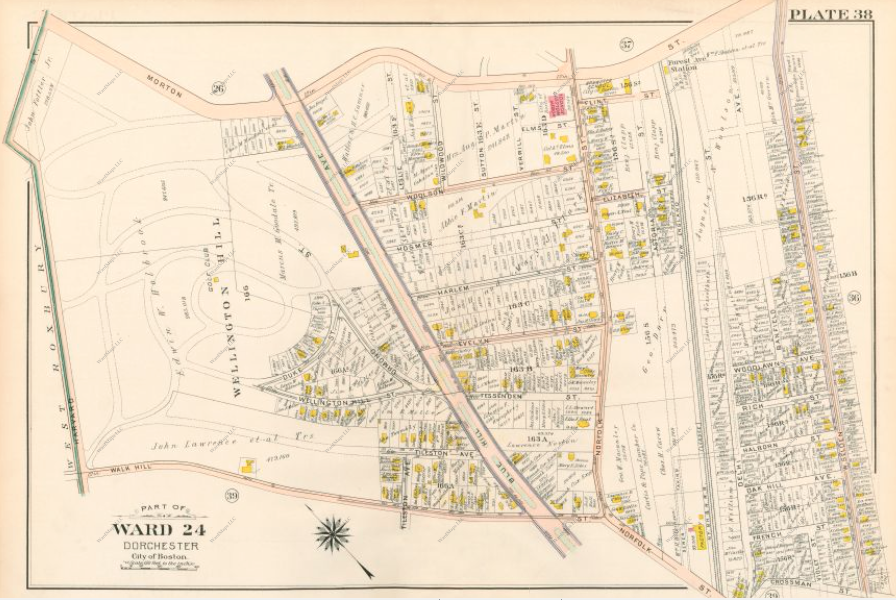

The last horsecar line in Boston, which was located in the Back Bay around Copley Square, stopped operating in 1900; therefore, it is reasonable to assume that by then the Franklin Park-Downtown horsecar line had been electrified. Accordingly, by 1904, significant new development has taken place around Blue Hill Avenue near Franklin Park. Still no storefronts, but plenty of triple-deckers!

1904 Bromley maps showing development at the time around Blue Hill Avenue near Franklin Park.

In 1906, electric streetcar trackage was extended further along Blue Hill Avenue all the way to Mattapan Square, with additional trackage being constructed along a roadside streetcar reservation on nearby Seaver Street to form a new line, 29/Mattapan-Egleston, that would serve the new Egleston Station that would open with the extension of the Washington Street Elevated (predecessor to modern-day Orange Line) further south down Washington Street from Dudley Square to Roxbury (see "Dudley Square" for more information) to Forest Hills in Jamaica Plain via nearby Egleston Square in Roxbury. Accordingly, by 1910, Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester was densely populated with a series of houses, apartment buildings and small businesses. The spur in development is most evident south of Franklin Park closer to Morton Street, where many new storefronts and triple-deckers now line the Avenue:

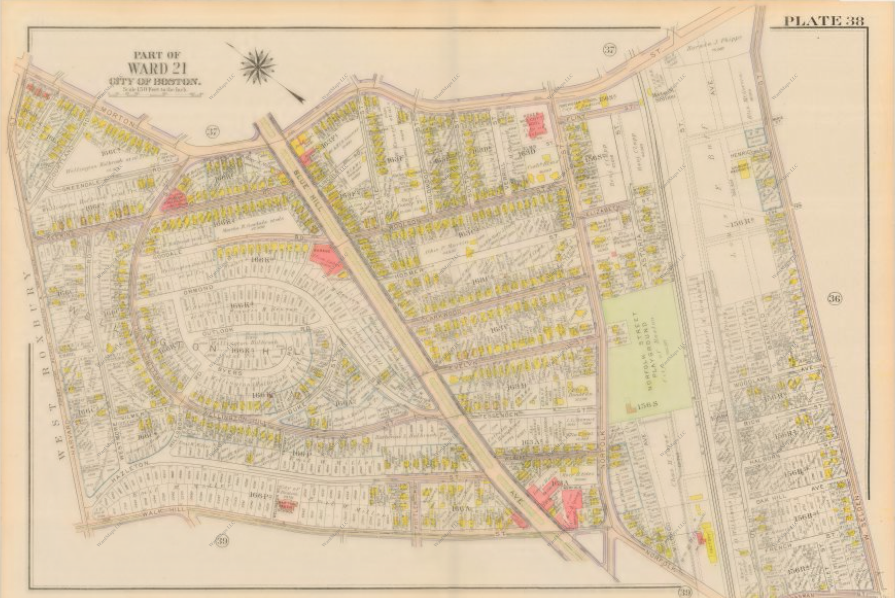

1910 Bromley Maps shooing development around Blue Hill Avenue by 1910.

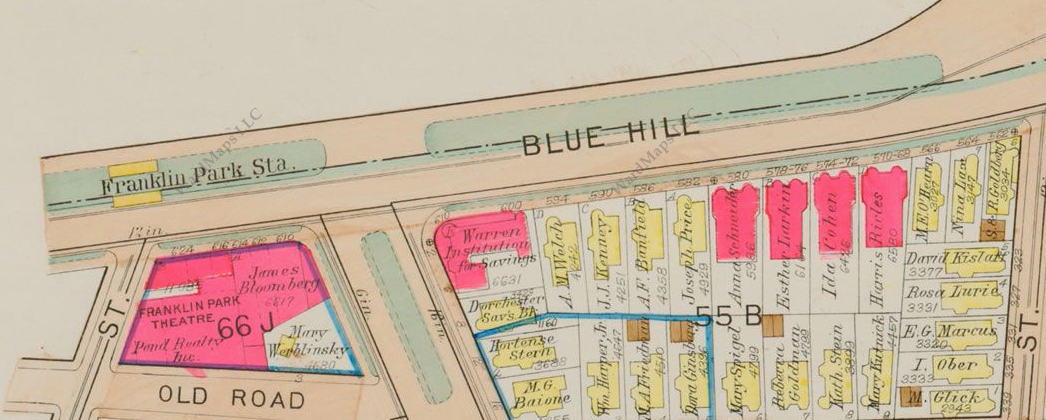

If you look at the first of the two 1910 Bromley maps, you can see that the roadside streetcar reservation by Franklin Park has been constructed. You can also see the center streetcar median on the second map, though the map does not indicate that either reservation carries streetcars. To better visualize the setup of the streetcar reservations on Blue Hill Avenue, check out the 1933 Bromley map below:

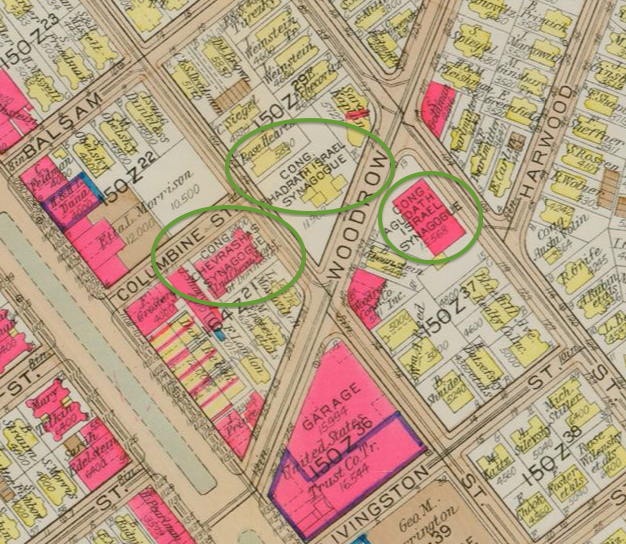

1933 Bromley Map of the area just by Franklin Park showing the streetcar reservation configuration on Blue Hill Avenue in the area. As you can see, there was a roadside reservation up until the end of Franklin Park, where the streetcars would cross Blue Hill Avenue's southbound lane and enter a center reservation as shown by the red arrow above. In the Google Map below, the red circle denotes the location of the reservation crossover point:

"Jew Hill Avenue:" Jewish Immigrants Arrive on Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester

The addition of reliable electric streetcar service, significantly streamlined by private reservations, to Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester further increased the area's already prime desirability as a place to live and visit. With affordable, newly-constructed real estate, a plethora of commercial resources and beautiful Franklin Park providing residents with a great place for recreation, Dorchester was now seen as a very nice place to live. Accordingly, many Jewish immigrants, who had previously lived in the West End, the North End or in Chelsea, moved to the area around Franklin Park and Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester in the early 1900s, seeking a nicer place to live with strong commercial infrastructure and easy access to public transit, the most sensible and affordable way to get around at the time.

The legend goes that on Seaver Street during the early 1900s, based on the area's significant Jewish population, landlords would post signs on apartments for rent that as a joke would read "Jews Need Not Apply." The Jews sure did apply though, and by 1920, there were about 25 synagogues in Dorchester alone serving a Jewish population in the area that occupied almost 100% of all housing around Blue Hill Avenue, which accordingly came to be called "Jew Hill Avenue," and Franklin Park.

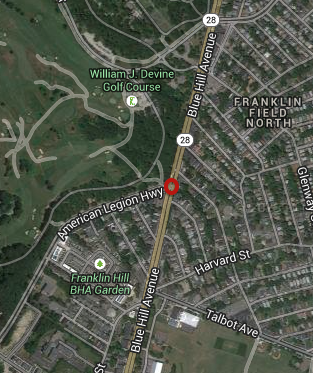

1933 Bromley map showing Woodrow Avenue in Dorchester, just off of Blue Hill Avenue in between Franklin Park and Morton Street. Circled in green are three Orthodox Jewish synagogues that were built centered around Woodrow Avenue across the street from each other, showing just how high the area's Jewish population was at the time!

Note that two synagogues are pink and one is yellow—two were built from bricks, and one from wood!

Note that two synagogues are pink and one is yellow—two were built from bricks, and one from wood!

Two of the former synagogues shown above, Hadarath Israel (left, built from wood) and Agudath Israel (right, built from brick) across the street from one another on Woodrow Avenue in Dorchester today, serving as proof for the once significant Jewish settlement in the area.

Subdividing Estates: Capitalizing Upon Dorchester's Transition from Country Wilderness to Urban Streetcar Suburb

1904 Bromley map also posted earlier of the section of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester between Franklin Park and Morton Street.

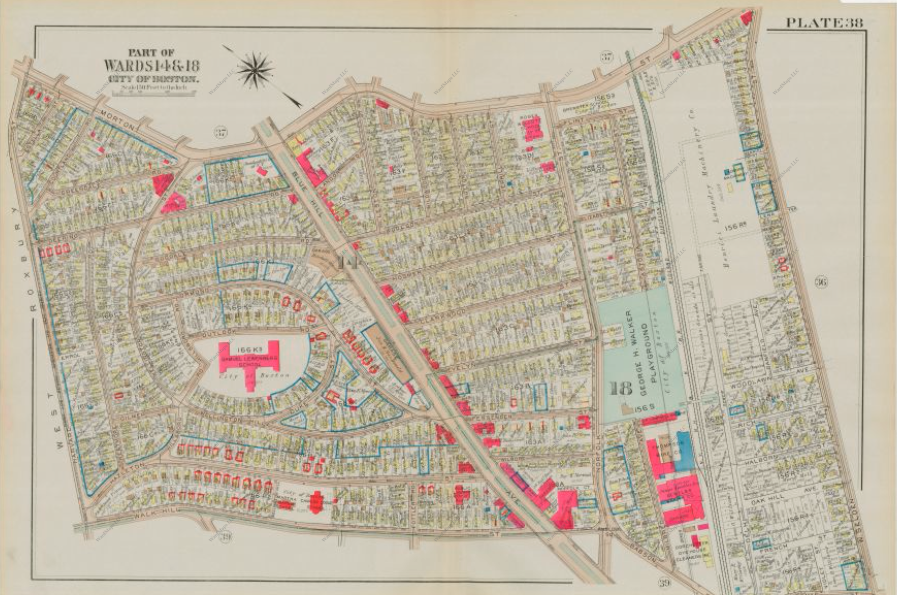

As you saw in the Bromley maps above, and as shown in the 1904 Bromley map reposted directly above, there were still sizable estates left in Dorchester in the 1900s. Seeing that Dorchester was going to become a major Boston "streetcar suburb," many estate owners capitalized upon the major influx of Dorchester residents and built multifamily real estate on the expansive land that was left in their possession. Take Wellington Hill, the residential neighborhood along Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan just by Morton Street, for example. (Note: Wellington Hill is also covered in my article "Streetcar Suburbs of Boston") Wellington Hill was part of a large estate inherited by Wellington Holbrook, a well-off graduate of Harvard College with a sharp mind and a great sense of business. Holbrook inherited his Hill in the early 1900s, when Dorchester was just beginning to become a major residential neighborhood. Holbrook's hill was located just off Blue Hill Avenue, yet it was also about a mile south of the Franklin Park horsecar loop, meaning that Holbrook would have to wait for a few years before he could make productive use of his land.

That opportunity came in 1906, when the 29/Mattapan-Egleston streetcar line entered service. Promptly, Holbrook developed his land with a street plan and a number of multifamily dwellings, dubbing the new neighborhood "Wellington Hill" after himself. Since his land was so conveniently situated by Route 29, hundreds of new residents flocked to Wellington Hill, and within a few years the Hill was a busy residential neighborhood with plenty of commercial resources available down on Blue Hill Avenue.

Bromley Map of Wellington Hill in 1904. Very little if any development has taken place on the Hill, though there are already streets outlined on the map in anticipation of Holbrook's impending development of his hill.

Bromley Map of Wellington Hill in 1910, by which time much more development, mostly residential, has taken place on and around Wellington Hill. Now that the 29 Streetcar runs by the Hill, many Bostonians want to live there.

Bromley Map of Wellington Hill in 1933. At this point, Wellington Hill is thoroughly developed, with scores of homes, a hilltop school and plenty of commercial infrastructure nearby on Blue Hill Avenue.

Holbrook's story is just one of many other similar stories of early 1900s Dorchester estate owners who were smart enough to capitalize upon their luck of owning land in one of the hottest neighborhoods in Boston at the time. By the 1920s, when Dorchester was a bustling suburb densely populated with multifamily dwellings and serviced by a number of streetcar lines and even a subway line (the Red Line, at the time called the Cambridge-Dorchester Subway, which stopped and still stops about a mile west of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester), there were no virtually no undeveloped estates left along Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester.

1918 Bromley map of the section of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester between Franklin Park and Morton Street, just north of Wellington Hill and Mattapan. Compare this map to the 1904 Bromley map of the area reposted again below, and you will see that just about every section of estate land has either been developed or subdivided and slated for future development.

Mid-1920s aerial view of Franklin Park (top left), Franklin Field (bottom left), Blue Hill Avenue (left) and the surrounding area. As you can see, virtually no land has been left undeveloped—every possible inch of land is covered with triple-deckers, two-family homes and businesses. Circled in blue is a Route 29 streetcar, the catalyst of Blue Hill Avenue's development, passing along Blue Hill Avenue, right over the switch through which Route 22 streetcars would enter Blue Hill Avenue from Talbot Avenue (the street along the top of Franklin Field). Image courtesy Boston Public Library.

1920-1960: The Transit-Driven Evolution of Blue Hill Avenue

Shops and businesses along Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan. Note streetcar infrastructure around which businesses are built.

Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

From the 1920s until the 1940s, Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester saw little change. Things were very relaxed and constant in Dorchester; people lived one of the many roomy apartments in Dorchester's triple-deckers and two-family houses and commuted to and from jobs in Boston on either streetcars or, if they lived closer to Dorchester Avenue, the Cambridge-Dorchester Subway. Dorchester was also a place where people would come to shop—Blue Hill Avenue in particular was lined with hundreds of businesses—furniture stores, fish markets, supermarkets, candy stores and just about anything you could think of could be found in Dorchester. The Franklin Park Theatre and other theaters on Blue Hill Avenue were popular entertainment destinations, as well as the multiple bowling alleys and restaurants that lined The Avenue.

Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester beside Columbia Road, with Franklin Park at the left and the Franklin Park Theatre at the right. The picture above shows the variety of purposes Dorchester served and still serves today—a residential neighborhood (apartments), a commercial district (storefronts) and a center of entertainment (Franklin Park & Theatre). Note the heavy car traffic by this time (1949) and that the 29 streetcar running along Blue Hill Avenue, circled in green (along with Columbia Road's 16 streetcar, which terminated at Franklin Park) runs in its own lane not mixed in with the cars.

Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

People would generally reach these businesses from Boston via streetcar or subway, as that was the most convenient way to get to Dorchester unless you owned a car, which was still a luxury at the time albeit less so with the advent of the Ford Model T and other lower-cost cars. Many Bostonians preferred to stick to the streetcars though, as car ownership was expensive and parking and driving in Boston were hassles just as they are today.

1933 Bromley map of the area around the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue and Columbia Road (map center). Note the variant of buildings in this area—many apartment buildings, as well as businesses and (on the far left) the Franklin Park Theatre. Also note Franklin Park Station on the 29 and 22 streetcar lines on the far top left; the 16 streetcar would cutback (switch ends) at the end of the Columbia Road streetcar reservation, the green strip at the center of Columbia Road (map center).

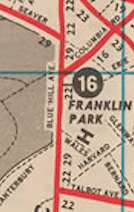

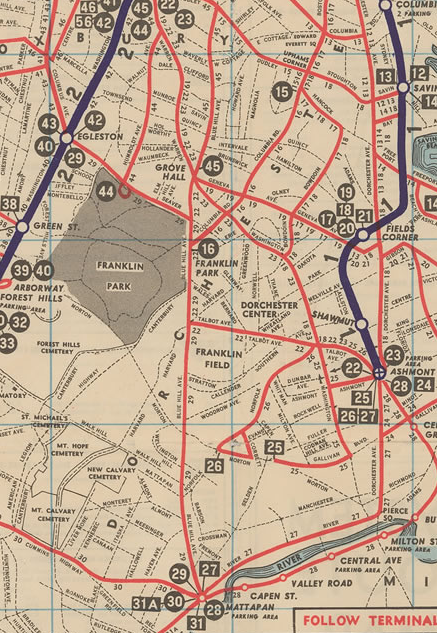

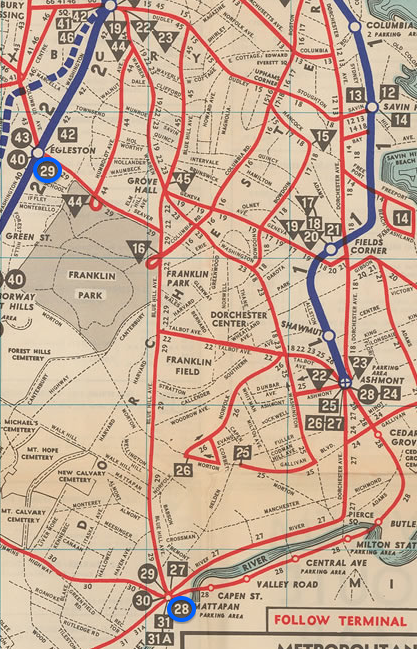

1948 BERy Map showing the streetcar lines that served the Franklin Park Area. In addition to the 29/Mattapan-Egleston streetcar, which joined Blue Hill Avenue from Seaver Street and continued south to Mattapan Square, the area had the 22/Dudley-Ashmont via Talbot Avenue streetcar, which would (traveling south) turn left off of Blue Hill Avenue onto Talbot Avenue in Dorchester, just south of Franklin Park (bottom of map above), and the 16/Franklin Park-Andrew streetcar, which would run from a cutback switch at the end of Columbia Road just by Franklin Park along Columbia Road to Andrew Square in South Boston.

The intersection of Columbia Road and Blue Hill Avenue, looking south on Blue Hill Avenue, with Franklin Park on the right. At left circled in blue is the 16 streetcar, and circled in green is a streetcar running on Route 29. On the left is the ornate building that housed the Franklin Park Theatre among other businesses, and shown in this photo further down Blue Hill Avenue are many more commercial developments (shops, restaurants, bowling alleys, Liberty Theatre, etc). Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

Change began hitting Dorchester's transit in the 1940s, when the streetcars that had served Dorchester so loyally for thirty years began to be replaced with trackless trolleys as the beginning of a series of changes that would come in order to accommodate the growing number of cars passing through the area.. The first trackless streetcar to trackless trolley conversion along Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester took place in 1949 on Route 22, which ran briefly along Blue Hill Avenue parallel to Route 29, following many other conversions further north on Blue Hill Avenue in Roxbury (on Routes 45 and 15 in 1948; Routes 23 and 19 in Dorchester were also converted from streetcars to trackless trolleys in 1949. Many other lines were changed over afterwards, and by 1950 the only streetcar line left in Dorchester was Route 29/Mattapan-Egleston via Blue Hill Avenue and Route 28/Mattapan-Ashmont (the Mattapan High-Speed Line).

1946 BERy map of the area around Blue Hill Avenue (center) in Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury. On a BERy map, a circle denotes a streetcar line, a rectangle denotes a bus line and a downward-pointed triangle denotes a trackless trolley line. As you can see above, trackless trolleys have not yet arrived in the area and there are still many streetcars operating.

1951 MTA map of the same area of focus. By now, there area only two streetcars orating in Dorchester, Mattapan or Roxbury—the 28 and 29, both circled in blue. The 30 also serves Mattapan Station, yet that streetcar spends most of its time in Jamaica Plain and Roslindale and runs through Mattapan briefly.

Blue Hill Avenue at Columbia Road in 1949, about three months after the streetcar-to-trackless conversion of Route 22; hence, we see trackless trolley wires (double wires) alongside the streetcar wires (single wires) above. Circled in red are two Route 29 streetcars, which will continue serving Blue Hill Avenue for a few more years. Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

The above southward photo of the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue and American Legion Highway provides another look at the late 1940s-early 1950s trolley infrastructure of Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester—tracks and single-wires at the center for Route 29, and double-wires at the right and left of the road for Route 22. Image courtesy City of Boston Archives.

Even Route 29, the main streetcar line along Blue Hill Avenue, was not immune to the changes that came with the advent of the car. By the early 1940s, Blue Hill Avenue was forced to accommodate heavy car traffic regularly as the most convenient and direct connector between the southern suburbs and Boston.

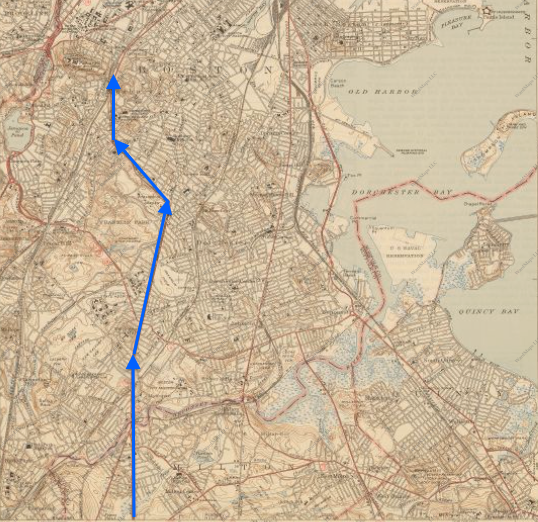

1946 US Geological Survey map showing the routes one would have taken to get to Boston from the south. Back then, there were no highways around Boston, so Blue Hill Avenue, as shown by the blue arrows, was the most direct route for a driver to take between the south and Boston. (This map was made two years before the Massachusetts DPW unveiled the master plans for the highways that would be built (and would not be built) in and around Boston in the coming years—see "Boston's Cancelled Highways" for more on the history of the development of highways in Boston!)

In response to said traffic, significant changes were made to Blue Hill Avenue to accommodate heavier levels of traffic. In 1941, the wide streetcar reservation on Blue Hill Avenue along Franklin Park was demolished and Blue Hill Avenue widened, with a new and much slower-moving center land designated for Route 29 (and then Route 22/Dudley-Ashmont via Talbot Avenue as well) streetcars.

The old roadside streetcar reservation on Blue Hill Avenue that ran along Franklin Park, Image courtesy Bradley Clarke. As you can see, the reservation took up quite a bit of space on Blue Hill Avenue; thus, when car traffic came to be too much for the narrower Blue Hill Avenue to hold, the reservation was demolished to allow for more room for cars to travel. See Blue Hill Avenue today (below) for comparison:

Compare the view above of present-day Blue Hill Avenue by Franklin Park to the photograph of the old park side streetcar reservation, and you will see that the old reservation that ran along Franklin Park took up almost the entirety of Blue Hill Avenue's present-day southbound lanes, from the stone wall (which dates back to Franklin Park's original construction) to the center greenery! The removal of the reservation allowed there to be two travel lanes in each direction on Blue Hill Avenue instead of one, significantly streamlining car travel on Blue Hill Avenue yet slowing down streetcars:

Blue Hill Avenue by Esmond Street, with Franklin Park to the right, sometime between 1941 and 1955. As you can see, the roadside streetcar reservation shown two photos ago has been demolished and there are now two lanes for cars in each direction, up from one each direction prior. Streetcars now run in their own lane in each direction by Blue Hill Avenue's median strip, still along their own right-of-way yet not as unimpeded as before, as the streetcars must now stop at traffic crossings, which they never had to do when running along the old roadside reservation by Franklin Park. Image taken from Sidewalk Memories, a documentary film chronicling Jewish Dorchester that I have posted at the end of this page.

Dorchester was also beginning to see a change in demographic by the mid-1940s, as the more affluent residents of the area began moving to suburbs such as Brookline and Newton where they could own more spacious homes with more land. Now that it was so much easier and cheaper to own a car, as there were many auto repair shops available and cars were no longer as expensive to make or buy, one could more easily afford to live further from Boston and commute by car.

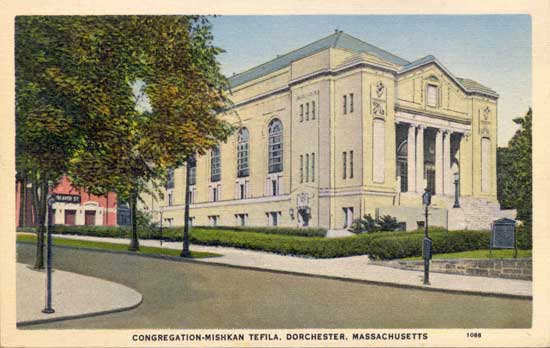

The year 1955 signaled coming changes to Dorchester that were to significantly change to the neighborhood. In 1955, along Franklin Park on Seaver Street in the Elm Hill neighborhood of neighboring Roxbury, Temple Mishkan Tefila, a large Conservative Jewish synagogue of hundreds of families, announced its impending departure for a beautiful new facility in Newton. While many Temple Mishkan Tefila members still lived in Roxbury, most had by now relocated to Brookline or Newton and commuted to Roxbury for services via private car or streetcar. The Roxbury facility, a beautiful classically-styled synagogue, was sold to a Lubavitch Ultra-Orthodox Jewish prayer group composed of a significantly less affluent clientele.

Mishkan Tefila as a synagogue in 1940, overlooking Seaver Street and Franklin Park. Image courtesy Dorchester Atheneum.

Mishkan Tefila's departure signaled Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury's move from primarily middle-class neighborhoods to diverse sections of Boston composed of primarily blue-collar residents, a composition that remains relevant to this day. Roxbury underwent such a shift first, and soon afterwards, in the 1960s, came Dorchester and later Mattapan in a southward wave of change along Blue Hill Avenue.

Also in 1955, and as a result of the advent of the car as well, streetcar Route 29/Mattapan-Egleston, the last streetcar line operating in Dorchester running along municipal roads, was switched over to a bus route. Such change was prompted by the reconstruction of Seaver Street to, of course, better accommodate increased car traffic. In 1955, Seaver Street still sported a wide roadside streetcar reservation along Franklin Park that had been connected to the similar reservation by Blue Hill Avenue that been demolished almost fifteen years previously. However, seeking to widen Seaver Street, which at the time still had only one travel lane going in each direction, the Boston Redevelopment Authority demolished the Seaver Street reservation in 1955 and proceeded to widen Seaver Street to a two, and in some spots three, lane in each direction road.

The old Seaver Street streetcar reservation photographed in 1955, months before its demolition and the end of streetcar service on Seaver Street and Route 29. As you can see to the right of the reservation, Seaver Street was a one lane in each direction road prior to the reservation's demolition.

Same location where the old Seaver Street reservation was pictured in 1955 today. As you can see, the streetcar reservation, which was once located between the eastbound (towards Blue Hill Avenue) lane of Seaver Street and the rocks along Franklin Park, has been demolished, and Seaver Street now has two lanes in each direction in this location (just by the intersection of Seaver Street and Blue Hill Avenue, looking west down Seaver Street).

Image copyright Google Maps.

Image copyright Google Maps.

In addition to detracting from the Seaver Street area's neighborhood feel, the demolition of the streetcar reservation spelled the end of streetcars on Seaver Street, as the MTA was reluctant to push for the construction of a continuation of the center lane for streetcars on Blue Hill Avenue onto Seaver Street as the center lane was convoluted and slow due to multiple traffic crossings on Blue Hill Avenue. Therefore, it seemed easier to just replace the streetcar line with a bus line. Accordingly, in 1955, Route 29 became a bus line and remains so to this day.

Blue Hill Avenue Today: Remnants of the "Streetcar Suburb"

Blue Hill Avenue today, with Franklin Park to the right, the old Franklin Park Theater (now a church) to the left and a bus running in place of the streetcars that once ran along the Avenue.

Since streetcars left Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester, the area has seen a radical change in demographic. As more and more Jews moved to Brookline, Newton and other suburbs of Boston in the 1960s, African-American residents began taking their place. By the early 1970s, Blue Hill Avenue from Roxbury to Mattapan was almost entirely surrounded by African-American households, earning the Avenue the new moniker "The Black Belt," with "Jew Hill Avenue" no longer relevant. Once could still find Jewish-owned business, and even some Jewish residents, along the Avenue, particularly in Mattapan, into the 1970s, but by the 1980s, virtually no active Jewish presence remained in Dorchester, Mattapan or Roxbury.

Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury remain predominantly African-American neighborhoods to this day. The businesses along Blue Hill Avenue serve similar functions—convenience stores, restaurants, barber shops, home supply stores— for the African-American community that they did for the Jewish community, although many of the classic entertainment destinations on Blue Hill Avenue, particularly theaters, have been closed down as part of the general modern-day American trend of preferring to be entertained at home by televisions and computers rather than in town at theaters, arcades and similar destinations.

Much of the original "streetcar suburb" development along Blue Hill Avenue remains today. For one, most of the original early 1900s housing and commercial built around Blue Hill Avenue's original trolleys remains standing to this day, densely planned in close proximity to Blue Hill Avenue. The trolley-oriented construction of Dorchester remains attractive to this day, as many of the area's current residents rely upon the public transportation (bus) that serves the Avenue today. Hence, Blue Hill Avenue is a prime example of Transit-Oriented Development, a phenomenon that is regaining popularity today as people seek to live nearby public transit and become less dependent upon cars.

A snow-covered Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester in the early 1960s, at which time the area was just beginning to experience a change in demographic. Much of the original "streetcar suburb" development, planned and constructed in close proximity to the streetcars that ran up and down the Avenue, remains intact, as it does today as well. Note the trolley pole at the far right of the photograph—this photograph was taken when Route 22/Dudley-Ashmont via Talbot Avenue was still operated by trackless trolleys; Route 29/Mattapan-Egleston, as is evident from the lack of streetcar wires at the center of the street, has since been bustituted. Image courtesy Boston Public Library.

While virtually no Jewish presence remain along Blue Hill Avenue, much also remains of Dorchester's former Jewish community. If one were to look closely at many of the wooden doorposts of the old triple-deckers and two-family homes, it is very likely one would find two holes across from one another vertically where a mezuzah (Jewish doorpost ornament) was once nailed in. Walk inside, and many of the kitchens still have two sinks so as to conform to Jewish dietary restrictions (Kashrut).

Many of the old synagogues that once served the area still remain today, occupied by churches and other community resources. Mishkan Tefila, for one, still stands proudly over Seaver Street and Franklin Park, today occupied by the United House of Prayer for All People church:

Examine the decorative stonework at either end of Mishkan Tefila's facade, and you will see that Jewish stars and Menorahs (Jewish candelabrums) remain there to this day. To either side of the Temple are apartment buildings; thus, the Temple itself is a prime example of construction in the era of Transit-Oriented Development, when multifamily homes were built almost adjacent to one another and all commercial and community resources were built within walking distance of trolleys and homes.

Walk down Elm Hill Avenue along Mishkan Tefila, and you will reach the Temple's old Hebrew school (Jewish equivalent of Sunday/Religious School), since converted to apartments, atop whose doorpost you will still find a Jewish star and the words "Mishkan Tefila." Look to the top of the building, and you will see that the Torah (Jewish holy book) proclamation "Thou shalt teach the Torah unto thy children" still remains there etched in stone:

Walk down Elm Hill Avenue along Mishkan Tefila, and you will reach the Temple's old Hebrew school (Jewish equivalent of Sunday/Religious School), since converted to apartments, atop whose doorpost you will still find a Jewish star and the words "Mishkan Tefila." Look to the top of the building, and you will see that the Torah (Jewish holy book) proclamation "Thou shalt teach the Torah unto thy children" still remains there etched in stone:

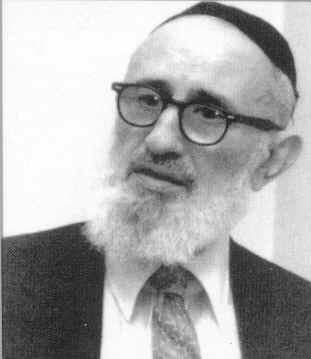

Elm Hill, the neighborhood of Roxbury along Seaver Street where Mishkan Tefila is located, is notable as the former home of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, commonly referred to as "The Rav," the father of the Modern Orthodox (fully Jewishly observant yet also fully active in secular society) Jewish movement. The Rav lived at 142 Homestead Street in Elm Hill, where he founded Maimonides School, a revolutionary educational institution which was one of the first Modern Orthodox Jewish schools in America. Maimonides School was originally housed at the Young Israel of Roxbury, an Elm Hill synagogue located at 161 Ruthven Street, and later moved between a variety of locations in Dorchester and Roxbury before moving to its permanent home on Philbrick Road in Brookline.

The Rav, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, in 1979. The Rav passed away in 1993 at the age of 90; more information on The Rav is available at therav.net, the source of the image posted above.

The Rav's modest home at 142 Homestead Street in Roxbury.

The former home of the Young Israel of Roxbury and Maimonides School at 161 Ruthven Street in Roxbury.

Many other former synagogues also remain in Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury. Shown earlier on this page are Hadarath Israel and Agudath Israel on Woodrow Avenue in Dorchester, just off of Blue Hill Avenue. Other significant synagogue structures that remain to this day are:

The former home of Congregation Chai Odom at 101 Nightingale Street in Dorchester, which today houses the Greater Love Tabernacle church and on which Jewish stars, the Tablets of the Ten Commandments (Jewish laws of utmost importance) and the words "Congregation Chai Odom" remain etched:

The former home of Congregation Chai Odom at 101 Nightingale Street in Dorchester, which today houses the Greater Love Tabernacle church and on which Jewish stars, the Tablets of the Ten Commandments (Jewish laws of utmost importance) and the words "Congregation Chai Odom" remain etched:

View of the bottom right edge of Congregation Chai Odom, where the Jewish calendar year 5682, the year the building was constructed, remain etched to this day:

The former home of Congregation Beth Pinchas at 61 Columbia Road, along the 16 streetcar route. Beth Pinchas was the synagogue of the "Bostoner Chassidic" movement, to this day the only Chassidic (Ultra-Orthodox) Jewish sect identified by an American city—a testament to how significant Dorchester's Jewish population once was. The "Bostoner Rebbe," the Rabbi of the synagogue and an important Boston religious figure, also took residence at 61 Columbia Road in Dorchester:

Adath Jeshurun, located at 401 Blue Hill Avenue in Grove Hall in Roxbury, a gigantic ornate building now occupied by the First Haitian Baptist Church on which Jewish stars remain etched. Note the sheer size of the structure, a testament to the tens of thousands of Jews that once called Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury home:

These are only a few of the many more former synagogues remaining in Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury. To see where even more synagogues were located, check out the Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury sections of the following listing of every synagogue to ever have been established in Massachusetts as a whole: http://jgsgb.org/pdfs/MassSynagogues.pdf

To gain more insight into the character of Jewish Dorchester, Mattapan and Roxbury, I recommend reading "The Death of an American Jewish Community" by Hillel Levine and Lawrence Harmon. Also watch "Sidewalk Memories," a documentary film on the topic that I have posted below: