The Building—and Cancellation—of Boston's Rapid Transit Extensions

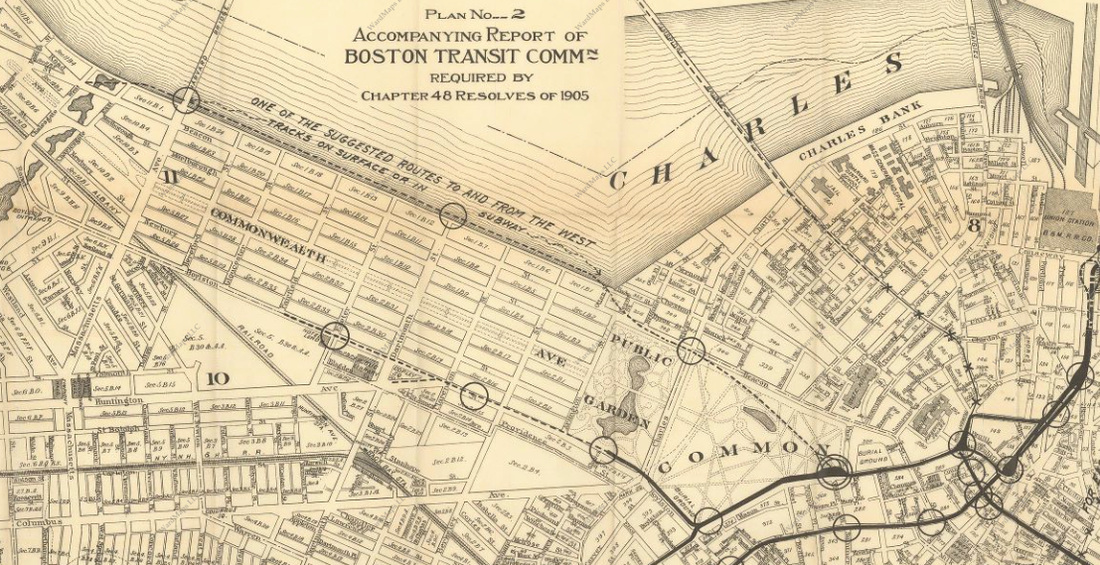

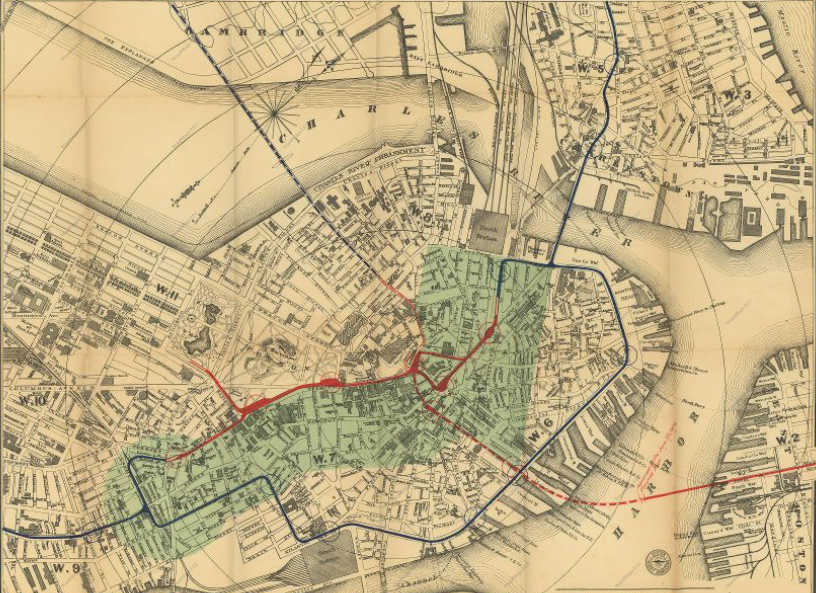

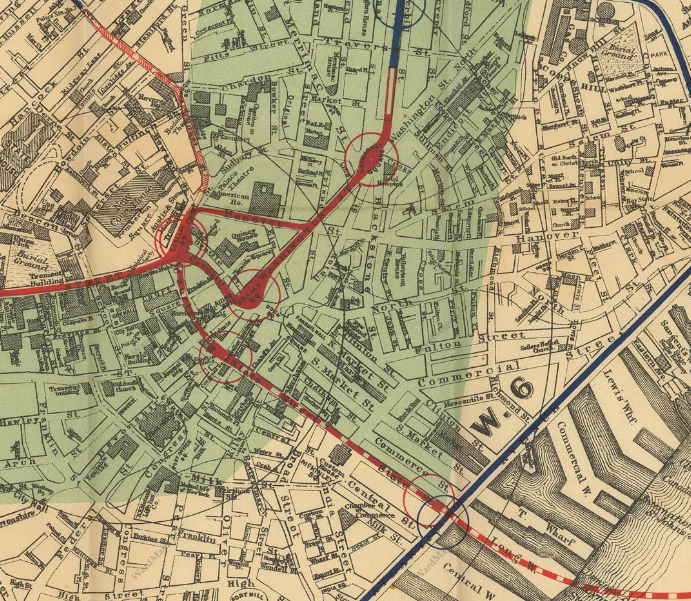

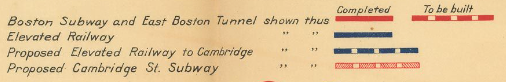

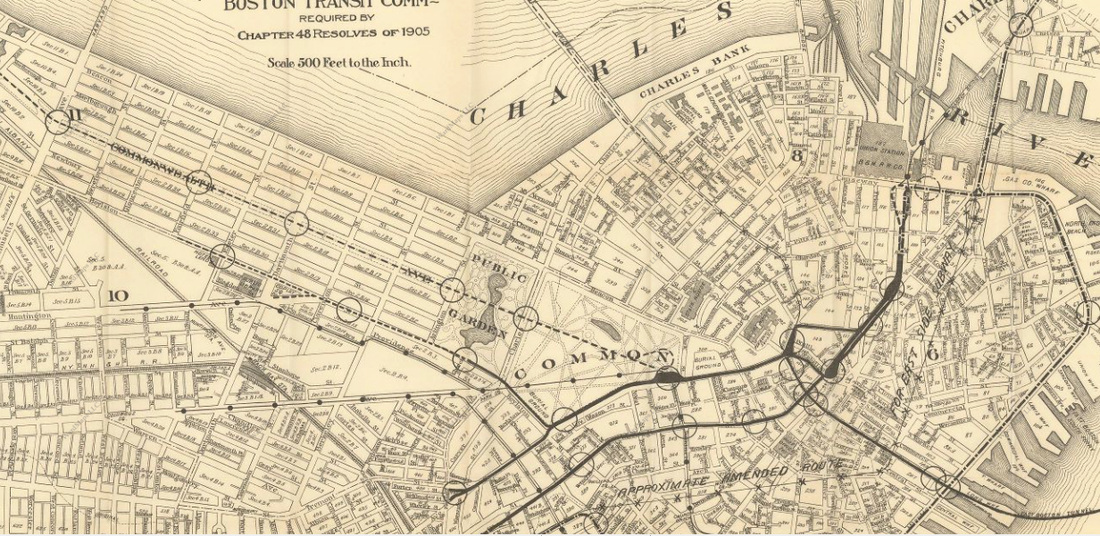

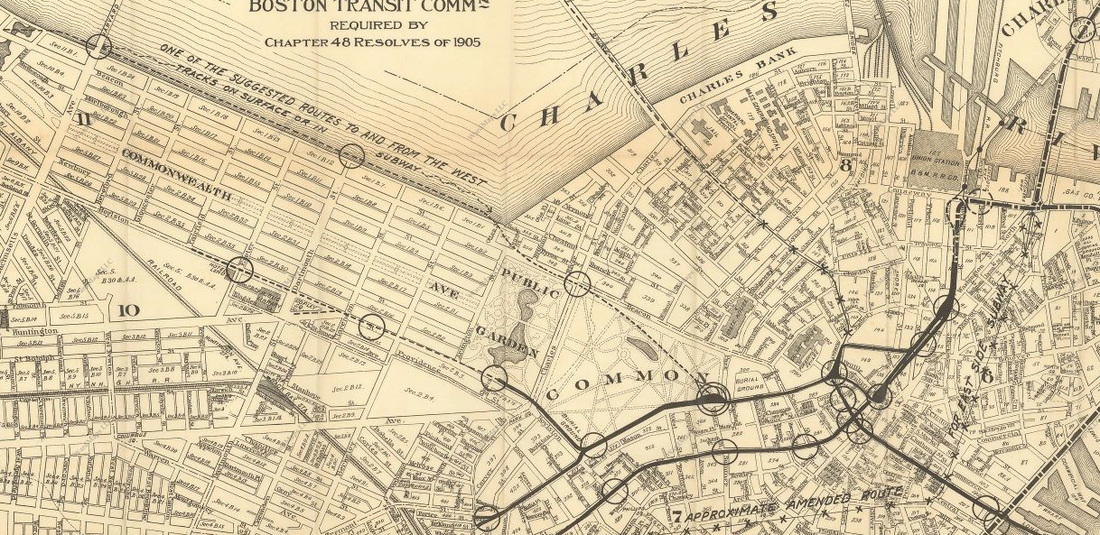

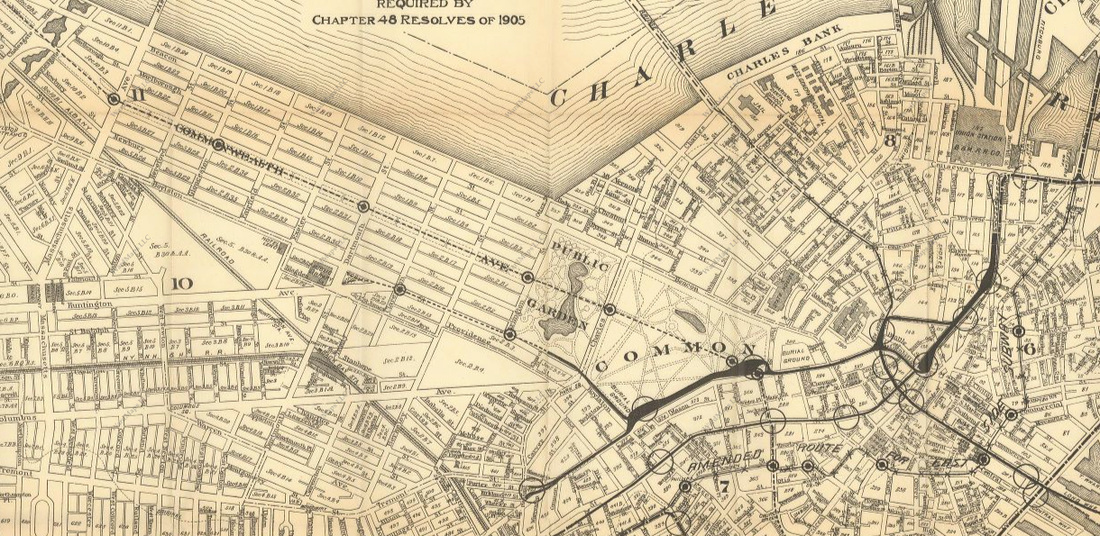

1906 Boston Transit Commission Annual Report showing proposed westward subway extensions along both Boylston Street and the Esplanade and a northward extension along Cambridge Street and across the Longfellow Bridge into Cambridge. Dotted lines = proposals, solid = existing.

As the city of Boston has grown over the years, the necessity to extend the reach of rapid transit lines has continued to grow. While trolley lines provided very reliable local transport, the construction of a more direct link to downtown was necessary was Boston to continue to expand. Not to mention that, as the city continued to grow, the streets of downtown became increasingly congested with car traffic and it became clear that, was transit to continue to function reliably, more rapidly-functioning lines would need to be built.

By the early 1890s, there were dozens of surface electric trolley lines operating in Boston, almost all of which ran into downtown to terminate around Park Square along Boylston and Tremont Streets. As you can imagine, the number of trolleys terminating in the area at once caused extreme congestion downtown—anyone wishing to travel in the area with a private vehicle would have had to wait in huge traffic jams!

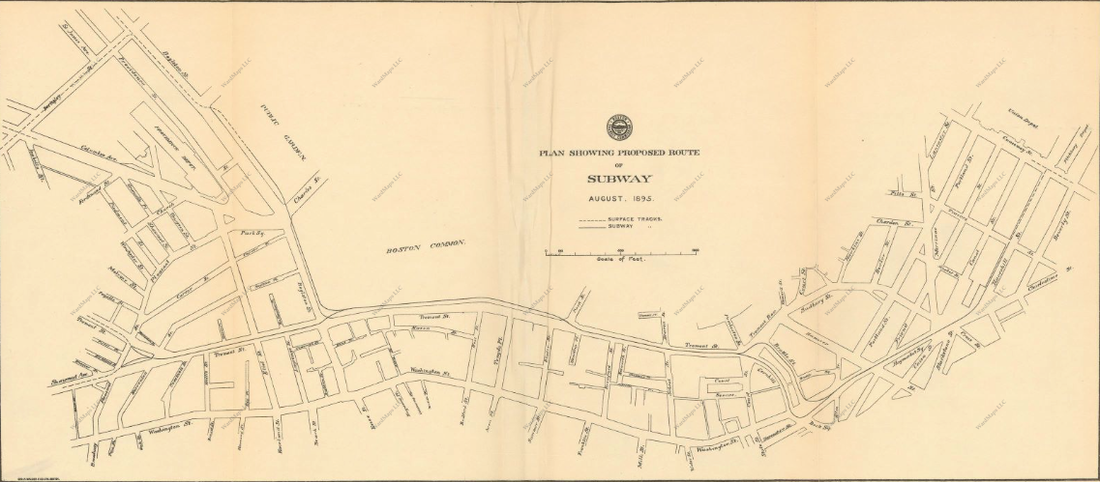

It became clear that something had to be done to get streetcars off of the streets and speed up transit in downtown Boston. Accordingly, in 1895, the first Boston Transit Commission was convened to discuss possible courses of action. Since the most pressing need for faster traffic flow was around Park Square, the first plan devised was a subway that would run under Boylston and Tremont Streets, continuing to Scollay, Adams and Haymarket Squares and ending in Boston's West End by North Union Station, an area that many streetcars coming from East Cambridge, Somerville and Charlestown passed through on their way downtown. Rather than run through the streets of downtown to reach Park Square, streetcars would feed into the ends of the subway and continue to Park Square underground, thereby speeding the flow of both transit and vehicle traffic.

Plan drawn up for Tremont Street Subway during the 1st Annual Boston Transit Commission in 1895.

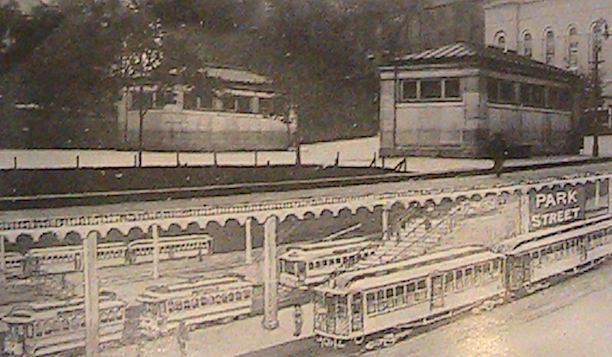

Construction on the new streetcar subway began in 1895, shortly after the Transit Commission, and continued for two years, extremely fast compared to the length of modern transit projects. The new subway opened on September 1st, 1897, with two entrances—one, the "Public Garden Portal," along Boylston Street, and another, the "Pleasant Street Portal," in Bay Village. Streetcars would enter at either of these locations and stop at two stations, Boylston and Park Street, before looping at Park Street.

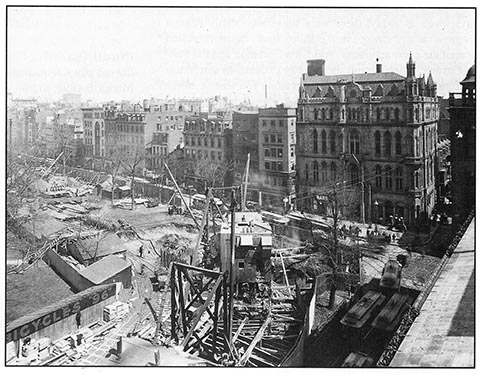

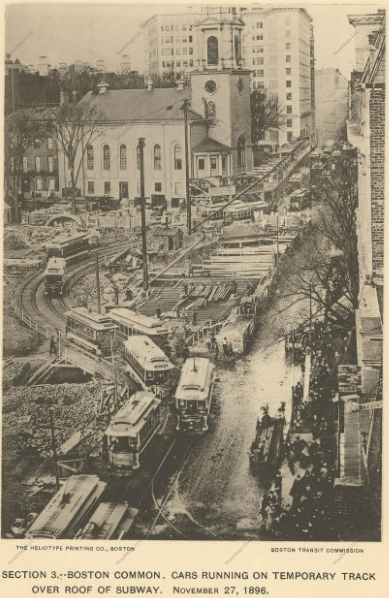

Photos of subway construction at Boylston and Tremont, along Boston Common. As you can see, there were many surface streetcar lines that ran through the area, causing high congestion.

A year later, in 1898, the entire streetcar subway had been constructed, extending past Park Street to Scollay, Adams and Haymarket Squares before concluding at the Canal Street Incline and North Union Station in the West End.

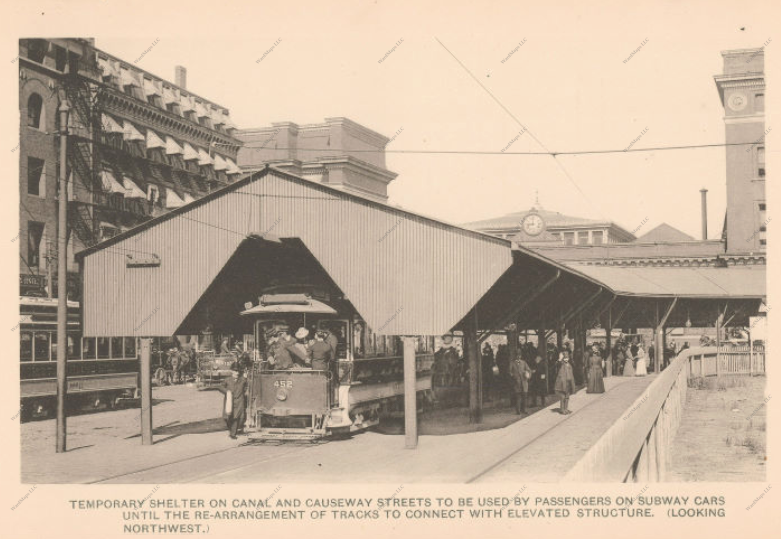

Surface streetcar platform by the Canal Street Incline used from 1898 to 1912. The large building with the clock up ahead is North Union Station; at left is Canal Street. While everything else in the area is gone today, the buildings along Canal Street remain as part of the Bulfinch Triangle, one of the few remnants of the old West End (more on the West End's demolition in "The West End's Transformation").

Note: to see how high streetcar traffic was in the West End and around Scollay Square, and how many streetcars would eventually feed through the Canal Street Incline at peak hours, check out this map from the 2nd Annual Boston Transit Commission in 1896:

http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=17202

http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=17202

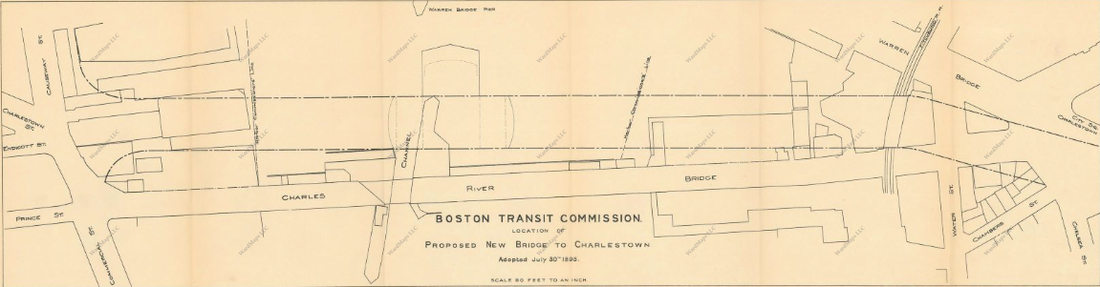

Meanwhile, while improvements were made to Boston's streetcar system, construction of a rapid transit link that would significantly change the dynamic of the city was underway. As early as 1895, in the 1st Boston Transit Commission, plans were drawn up for a new bridge over the Charles River to link Charlestown and the North and West Ends. The new bridge would be a multimodal transit investment, carrying streetcars, personal vehicles and, above street traffic, a new elevated railway.

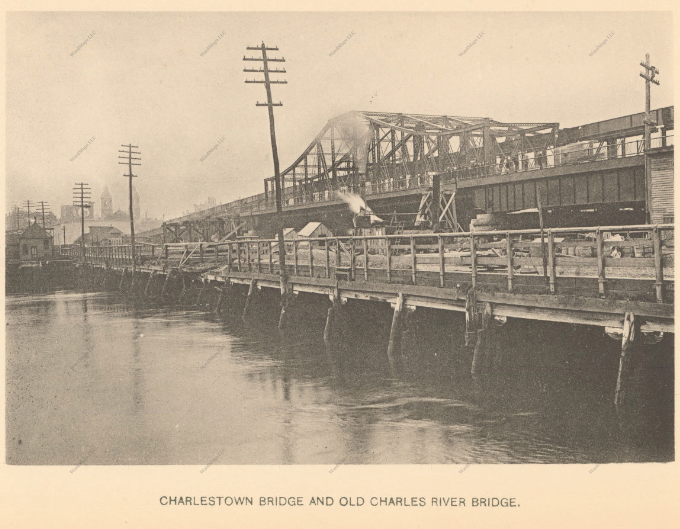

Proposal for the new Charlestown Bridge drawn up in 1895 and included in the 1st Boston Transit Commission Report. The new bridge would replace an earlier bridge, the Charles River Bridge, visible in the sketch above as well as in the photo below alongside the under-construction Charlestown Bridge/El:

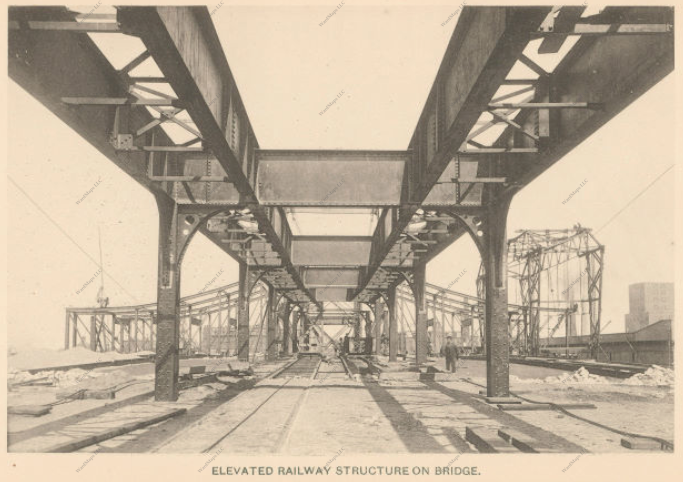

Charlestown El construction progress on the Charlestown Bridge in 1899. Note that the bridge will also carry streetcars below the El.

The new "El" would serve a large area of Boston. Upon its inaugural run in 1901, the new train ran on an elevated structure from Sullivan Square in Charlestown to North Station in the West End, where it would run through the Tremont Street Subway (which the "El" shared with streetcars) to the Pleasant Street Portal. From Pleasant Street, "El" trains would rise onto a second elevated structure that ran above Washington Street in the South End and terminated at Dudley Square in Roxbury. A few months later, a second route for the "El" through downtown opened, routing trains above Atlantic Avenue along Boston's Waterfront as opposed to sending them through the Subway.

Map taken from the 1902 Boston Transit Commission report showing rapid transit lines concentrated around downtown Boston. In solid red is the Tremont Street Subway, and in solid blue is the El. Note the dotted red line under Boston Harbor—this is the East Boston Tunnel, soon to be explained.

The Washington Street Elevated under construction in Roxbury in 1900. Image courtesy Ward Maps.

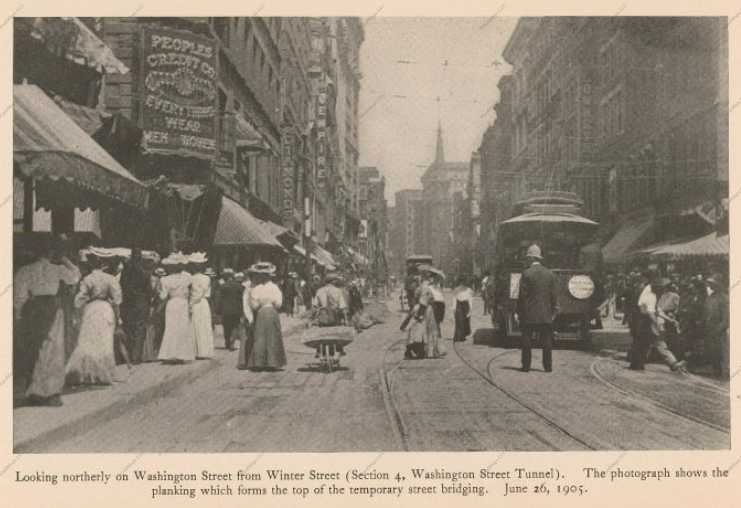

Sharing the Tremont Street Subway was not intended to be a permanent solution for the El. The setup proved impractical, as it meant that streetcars could not use the Pleasant Street Portal and could not run past Park Street northbound. Accordingly, in 1905 construction began on a new subway tunnel downtown exclusively for El trains. The new tunnel opened in 1908 and to this day runs under Washington Street downtown, under a section of the street once called Orange Street (hence the later name "Orange Line" for the El). After the Washington Street Tunnel's opening, use of the Pleasant Street Portal and the entire Tremont Street Subway was once again reserved for streetcars.

Diagram showing the layout of Park Street Station while the El shared it with streetcars. Coming to Park from Boylston, Streetcars would use the inner track, which to this day leads to the loop that sends streetcars back towards Boylston Station, and El trains would use the outer track, which allows trains to continue onward towards North Station.

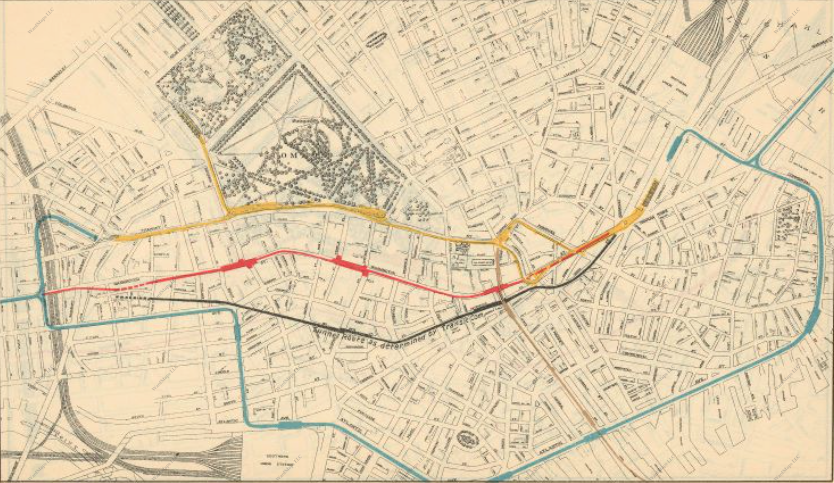

Map from the 1904 Boston Transit Commission report showing projected rapid transit downtown. In yellow are streetcar tunnels (Tremont Street, East Boston), and in light blue are Els. In red is the to-be-constructed Washington Street Tunnel, and in black is an alternate route suggested for the El's tunnel that was rejected.

1905 Boston Transit Commission photograph showing Washington Street paved with wooden planks, under which is the under-construction Washington Street Tunnel.

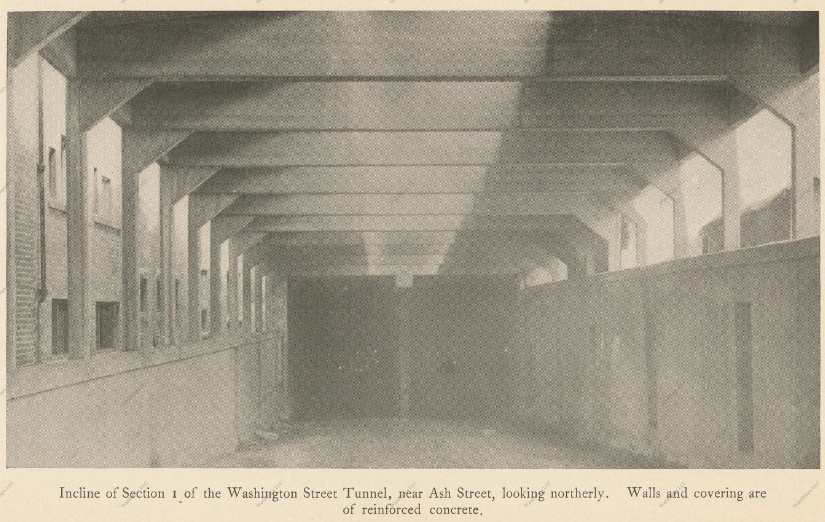

Under-construction Washington Street Tunnel southern incline by Bay Village.

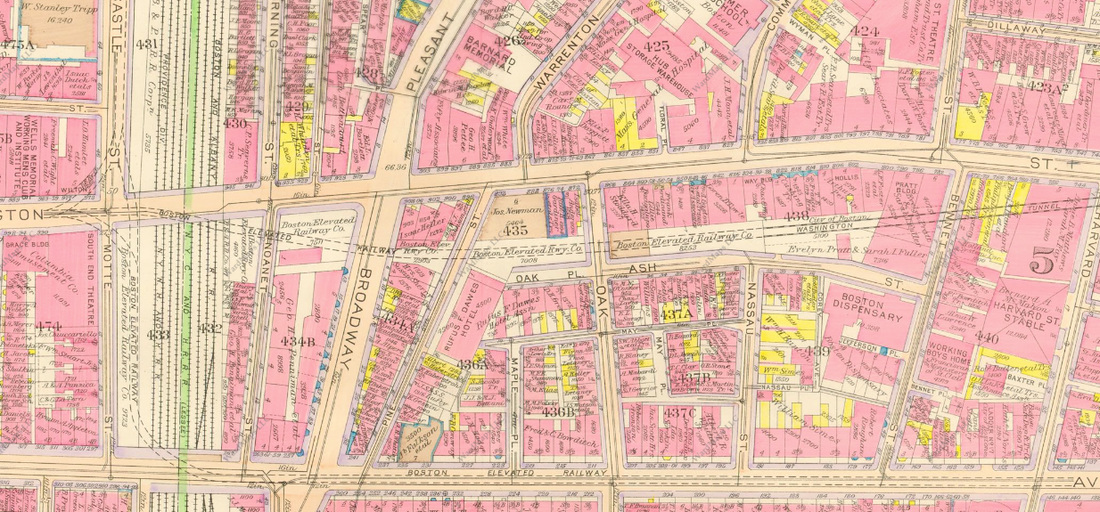

Path of the El from the South End to the Washington Street Tunnel—the El would cross the Boston and Albany Railroad right-of-way that later became the Mass Pike on the Washington Street Bridge and then veer right on elevated supports to enter the portal, which was located at the corner of Oak and Ash Streets. Map is a 1917 Bromley map.

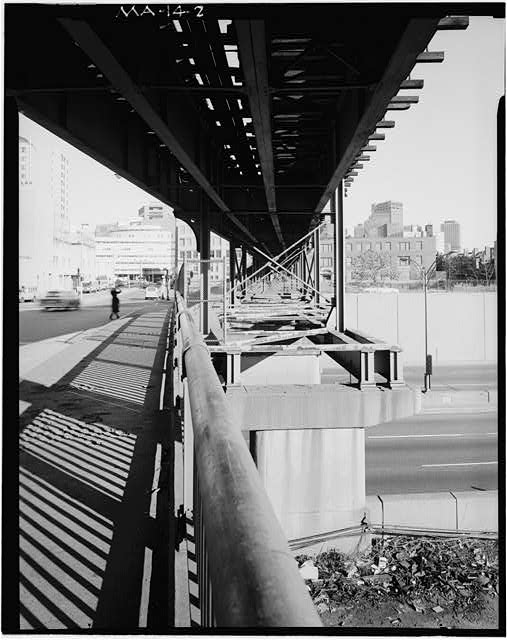

At left, the El diverging right from the Washington Street Bridge into downtown. At right, the El's old portal at Oak and Ash downtown.

Both photos taken in 1982.

Both photos taken in 1982.

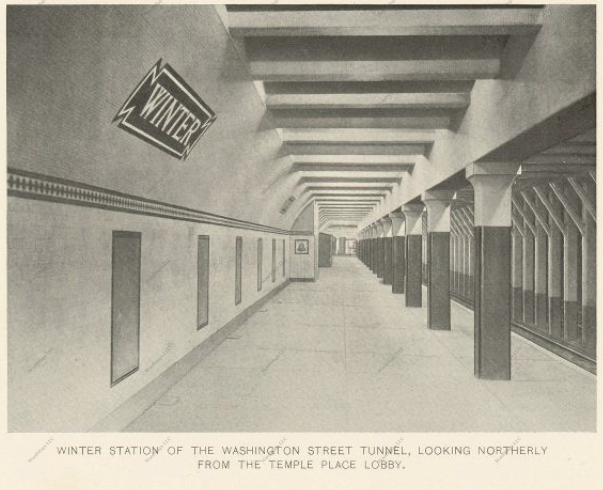

Just-opened Winter (Downtown Crossing) Station on the Washington Street Tunnel from the 1908 Boston Transit Commission report.

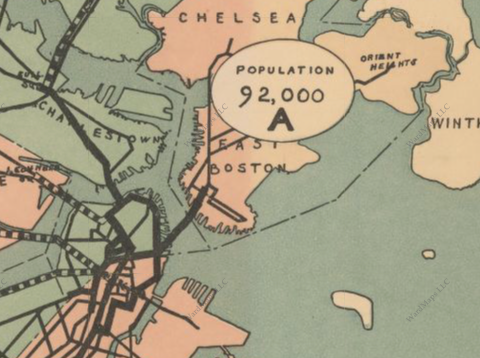

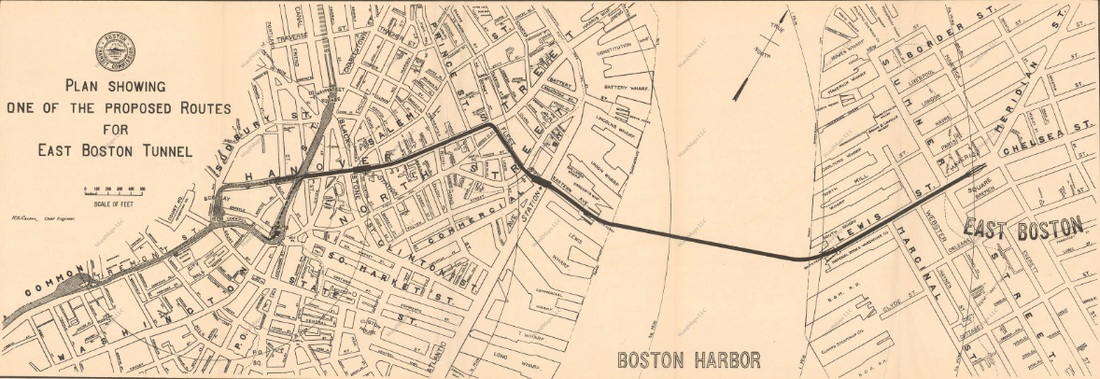

We now turn the clock back nine years, to 1899, to hear about an additional 1900s subway, the East Boston Tunnel. A proposal was first drawn up in 1899 for a tunnel that would carry streetcars from East Boston to downtown under Boston Harbor:

1900s Boston Elevated Railway (BERy) map showing how BERy streetcars fed into the East Boston Tunnel and crossed Boston Harbor to reach downtown—previously, BERy streetcars had no way of getting downtown.

Prior to the East Boston Tunnel's construction, streetcars from East Boston had no way of reaching downtown—the only public transit option linking the two was the Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad's ferry from Jeffries Point. The tunnel would allow streetcars to cross Boston Harbor, thereby allowing for through streetcar service from East Boston to downtown:

A proposed route for the East Boston Tunnel, running from Maverick Square in East Boston to Scollay Square downtown, from the 1899 Boston Transit Commission report.

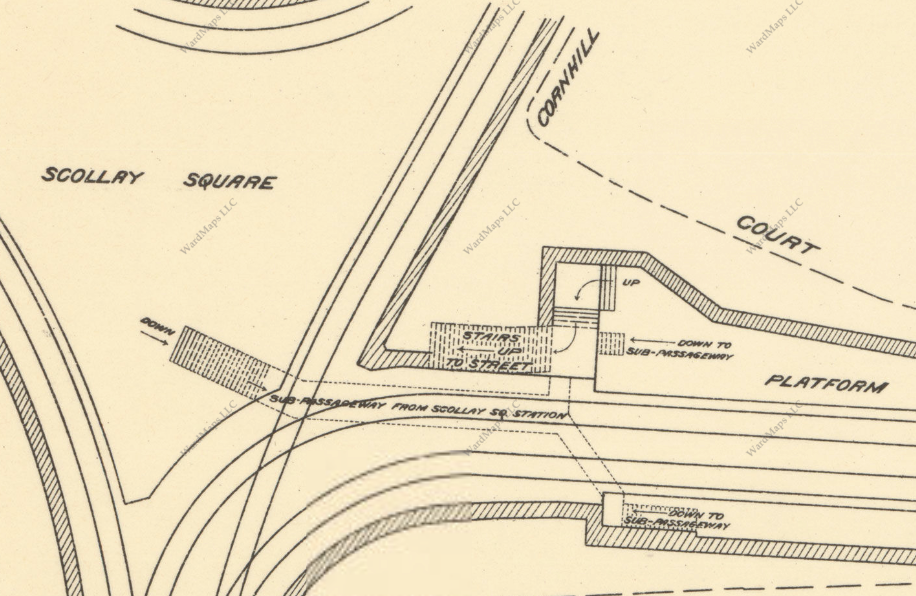

Original plans for the East Boston Tunnel, visible above, had the tunnel entering downtown at Ballards Wharf by the North End and running under Hanover Street in the North End to meet the Tremont Street Subway by Scollay Square, first stopping at Scollay Square Station and then looping and returning to the East Boston Tunnel via Adams Square Station. Ultimately, these plans were scrapped in favor of a route that would enter downtown at Long Wharf, providing a connection with the Atlantic Avenue Elevated at Rowes Wharf Station, and continue under State Street, through the heart of downtown, to reach Scollay Square at a dedicated station, Court Street Station, located walking distance from Scollay Square Station on the East Boston Tunnel.

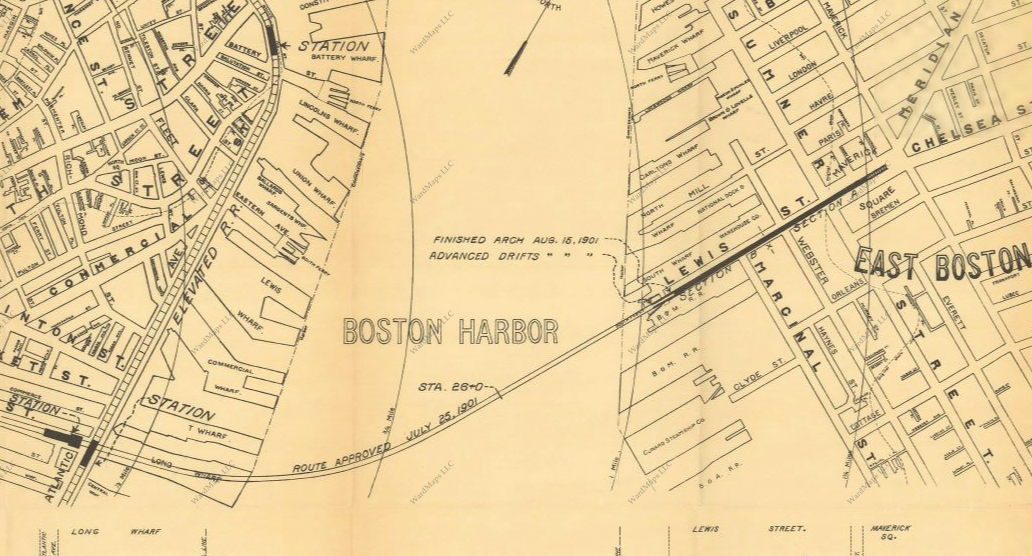

Map from the 1901 Boston Transit Commission report showing the approval of the East Boston Tunnel's route under Boston Harbor to reach Long and Rowes Wharves downtown, and the already-complete construction of the East Boston Tunnel in East Boston.

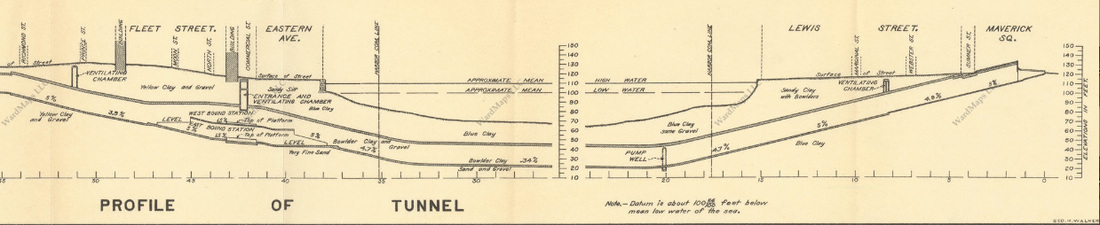

Engineering diagram from the 1900 Boston Transit Commission report showing the East Boston Tunnel's path across Boston Harbor.

Map from the 1902 Boston Transit Commission report showing the final route of the East Boston Tunnel from Long Wharf to Scollay Square. The line is solid and dotted because the tunnel is currently under construction. Note that the map does not show Court Street Station as a separate station—it was almost adjacent to Scollay Square, which is marked as a double-level station (two circles). The intermediate station downtown is State Street.

Plan for Court Street Station taken from the 1903 Boston Transit Commission report. As you can see, the station is adjacent to Scollay Square Station on the Tremont Street Subway and is connected by a sub-passageway.

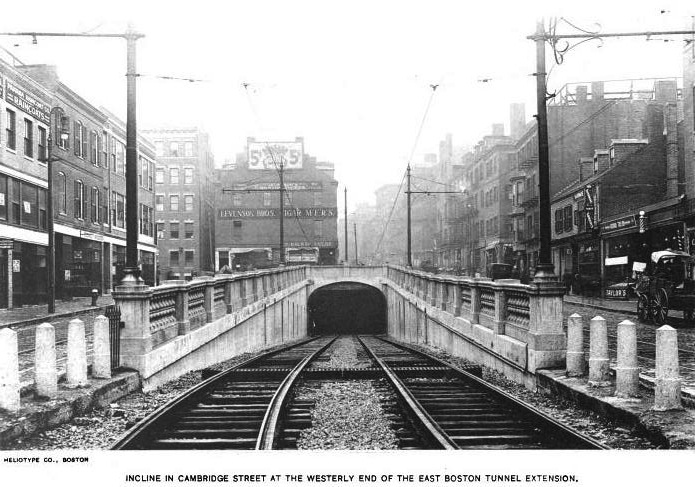

In 1916, the East Boston Tunnel was extended to Bowdoin Square, and Court Street Station ceased to be a stop. The platforms and station signs still remain yet are not easily visible from passing Blue Line cars. The subway continued past Bowdoin to a portal in Cambridge Street by Joy Street, the Joy Street Portal, allowing streetcars to emerge onto the street and continue onward to Cambridge, typically to Harvard Square.

1917 BERy map taken from the 1917 Boston Transit Commission report showing that the East Boston Tunnel has been extended to the intersection of Cambridge and Joy Streets, circled in red, and that streetcars in the tunnel now stop at Scollay Square Station and at a new stop in Bowdoin Square.

Photo of the Joy Street Incline, from which East Boston Tunnel streetcars would continue onward to Cambridge.

Postcard showing the Longfellow Bridge connecting Boston and Cambridge as it looked when originally constructed. When the bridge was chartered, a ROW for rapid transit was included in the center—though it was not originally clear which line would use it.

Map taken from the 1902 Boston Transit Commission report showing a proposal for a "Cambridge Street El" extending the East Boston Tunnel to the Longfellow Bridge and over the bridge to Cambridge, thereby sending the tunnel's streetcars along the present-day Red Line's northern route.

Map key from the 1902 map above showing the color keying and specifically mentioning the "proposed elevated railway to Cambridge."

It was originally proposed to extend the East Boston Tunnel right-of-way all the way to Cambridge via a "Cambridge Street El" that would connect with the Longfellow Bridge. Ultimately, this was not constructed, though nowadays, with the necessity for a Red Line-Blue Line Connector extending the East Boston Tunnel ROW along Cambridge Street to Charles/MGH Station on the Red Line, the proposal has resurfaced: Amatuer Planner's Proposal for a Cambridge Street El

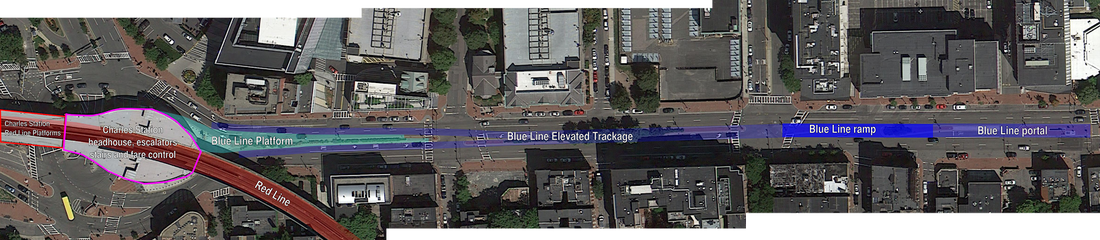

Amateur Planner's March 2014 diagram showing a plan for a Cambridge Street El that would serve as a Red Line-Blue Line Connector.

Following the East Boston Tunnel's completion in 1904, additional plans were drawn up for new subways to be constructed. Critical areas of service were the Back Bay and downtown, where the most road congestion occurred due to the number of streetcars in the streets. In the 1906 Boston Transit Commission report, three plans were proposed moving forward:

First, for two subways to be built in the Back Bay—one under Commonwealth Avenue between Park Street Station and Kenmore Square, and the other as an extension of the Tremont Street Subway to Fairfield Street in the Back Bay. The East Boston Tunnel ROW would be extended to Cambridge, and a new East Side Subway would be built through downtown with later additions of Huntington Avenue and Columbus Avenue subways:

Second, for the Boylston Street and East Side subways to be built, along with the extension of the East Boston Tunnel ROW into Cambridge and a new route along the Esplanade, the "Riverbank Subway," form Park Street to Kenmore:

Third, to build the Boylston Street Subway, along with the East Side Subway, Commonwealth Avenue Subway and extension of the East Boston Tunnel ROW into Cambridge:

Ultimately, none of these plans came to full fruition. By 1910, it had been decided to build two new subways, both rapid transit lines—one in a new tunnel under Beacon Hill to run from Park Street to Cambridge, and another running from Park Street to Kenmore via the Esplanade—plus an elevated railway and viaduct to bring streetcars from North Station to Cambridge.

1910 Boston Transit Commission map with existing and proposed subways.

Both ROWs to Cambridge would be built and running by 1912. The elevated railway and viaduct came to be known as the Causeway Street Elevated and Lechmere Viaduct:

Lechmere Viaduct around the time of its opening in 1912 by Charles River Dam, present location of the Boston Museum of Science. At this time, there are still some streetcar lines using the surface streetcar tracks alongside the viaduct; soon afterwards, the tracks will be paved over and all streetcars will use the viaduct:

Leverett Circle, crossover point from the Lechmere Viaduct to the Causeway Street Elevated in about 1925, by which time the streetcar tracks below have been paved over. Note that in 1922, BERy opened Lechmere Station at the end of the Viaduct, ending direct streetcar trips from Somerville and Cambridge downtown—riders would now have to transfer at Lechmere. Also note that virtually none of the buildings in the West End up ahead exist today—virtually all of them fell victim to the West End Urban Renewal (more on that in "The West End's Transformation"). Even Leverett Circle is no longer a circle today—the small park at center is now the site of the entrance to Science Park Station, which opened here on the Viaduct/El in 1955 to serve riders headed to the then-new Boston Museum of Science:

2013 view of Science Park Station at the intersection of the intersection still referred to as Leverett Circle. Note the green elevated supports—these, as well as a second section at the other end of the Viaduct by Lechmere, are the last remaining examples of riveted metal elevated rapid transit construction in Boston.

The Beacon Hill Tunnel and Cambridge Rapid Transit line, running from Park Street to Harvard Square, opened in 1912 and would eventually become the Red Line:

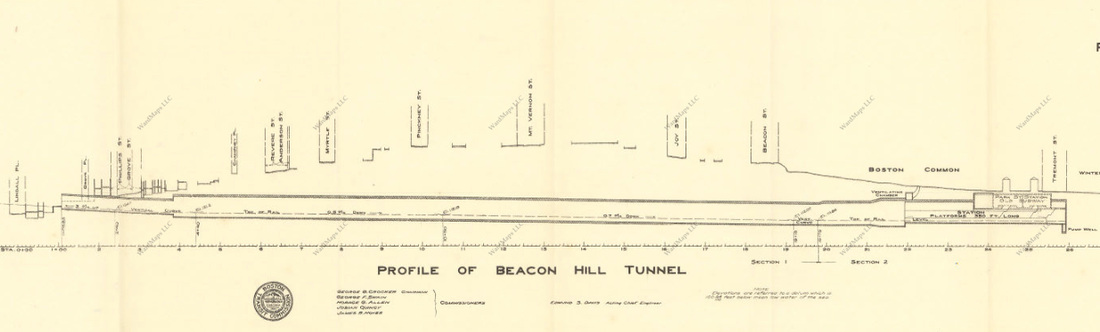

Construction profile of the Beacon Hill Tunnel from the 1910 Boston Transit Commission report.

The Riverbank Subway, however, was never built. In its place, the Boylston Street Subway was built:

Snapshot of the 1913 Boston Transit Commission's map of present and proposed transit extensions showing the newly-opened Cambridge Rapid Transit Extension and the soon-to-be-constructed Boylston Street Subway.

The Boylston Street Subway opened in 1914 and is used today by the Green Line. The tunnel took streetcars off the streets of the Back Bay, running all the way to Kenmore Square from Park Street Station:

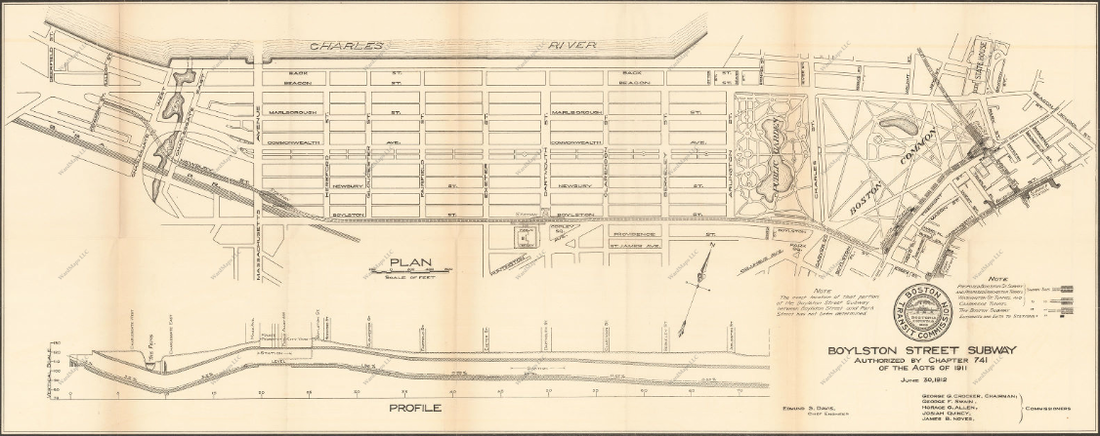

1912 Boston Transit Commission report plan for the Boylston Street Subway.

While the Boylston Street Subway was being constructed, an initial plan to extend Boston's streetcar subway to Post Office Square resurfaced. When the Tremont Street Subway was built, a provision was included for an extension to Post Office Square, a major hub for business and the location of the city's main post office. The new line would connect with the Washington Street Tunnel at Essex Station and would make it much easier for the Postal Service to use streetcars to deliver mail. Ultimately, this extension was not constructed, though the provision, a small dead-ended tunnel branching off of the subway just after Boylston Station, remains to this day.

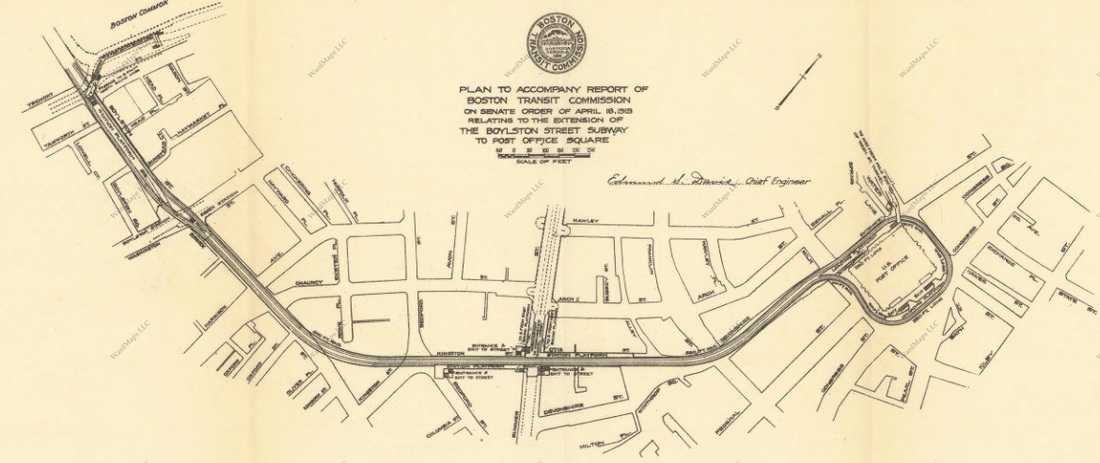

1913 Boston Transit Commission report plan for the Post Office Square extension of the Boylston Street Subway. The subway would have circled around the US Post Office, allowing for streetcars to be loaded with mail to be delivered.

A streetcar used for mail delivery in Boston.

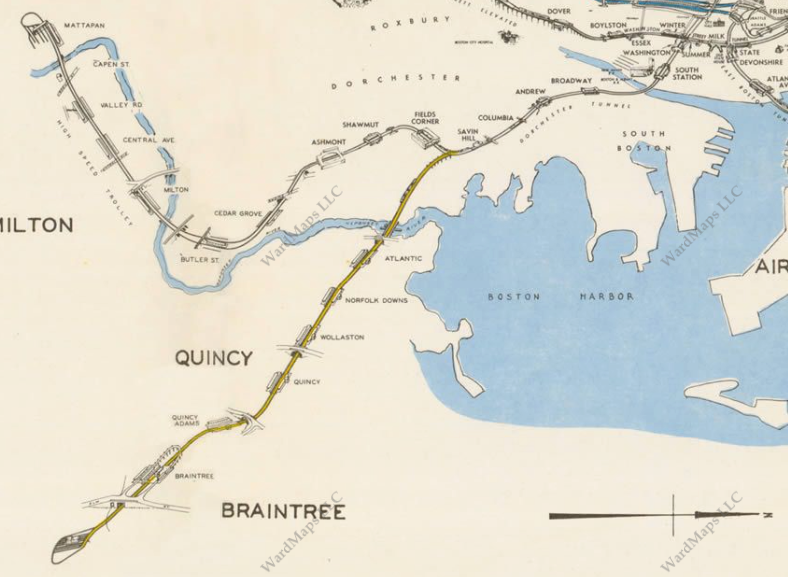

Next to come was a southward extension of the Cambridge Rapid Transit Line to South Boston and Dorchester, two of Boston's most densely-populated residential neighborhoods. The new line would open in sections—by 1918, the subway would run to Andrew Square in South Boston. In 1926, the Boston Elevated Railway acquired the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad's southern "Old Colony" ROW, and converted that to the Dorchester Extension—by 1928, the "Cambridge-Dorchester Rapid Transit" ran all the way to Peabody Square in the Ashmont section of Dorchester. By 1929, the Ashmont-Mattapan High-Speed Trolley was complete, bringing rapid transit riders to Mattapan Square in Mattapan via streetcar:

Map from 1913 Boston Transit Commission report showing the proposed construction of the extension of the Cambridge Rapid Transit line to Andrew Square in South Boston via a tunnel under the Fort Point Channel.

Snapshot of 1936 BERy map showing the Cambridge-Dorchester Rapid Transit's path from Park Street to Ashmont, and then the path of the Ashmont-Mattapan High-Speed Trolley, then numbered 19.

After the completion of the Red Line Extension in 1929, no more significant rapid transit extensions were built for over twenty years. The exceptions are:

A) The slight extension of the Boylston Street Subway under Kenmore Square, which opened in 1932, built to bring the streetcars lines that are now the B and C Lines of the Green Line (and then the A Line as well) to their reservations without having to mix in with Kenmore Square traffic, which had become very heavy by the late 1920s.

A) The slight extension of the Boylston Street Subway under Kenmore Square, which opened in 1932, built to bring the streetcars lines that are now the B and C Lines of the Green Line (and then the A Line as well) to their reservations without having to mix in with Kenmore Square traffic, which had become very heavy by the late 1920s.

View of Kenmore Square traffic prior to construction of the Kenmore Square Subway, when streetcars had to cross Kenmore Square on the surface, requiring them to stop at a traffic crossing before entering the surface station and causing streetcar traffic to back up.

The new Kenmore Square Subway under construction. In a few years, the Kenmore Portal through which streetcars now enter the Boylston Street subway will become a subway ventilation shaft, a role it continues to play today.

B) The construction of the new Huntington Avenue Subway between Copley Square and Northeastern University, which opened in 1941, bringing 39/E Line streetcars off of Huntington Avenue and Boylston Street downtown and into the Boylston Street Subway (more on the Huntington Avenue Subway in "E Branch").

Surface streetcars at the intersection of Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues in 1920.

Streetcars on the Huntington Avenue streetcar reservation in 1920, in front of the Mechanics Building and Boston and Albany Railroad rail yard by Copley Square (to see just how much Copley Square has changed over the years, check out "Copley Square").

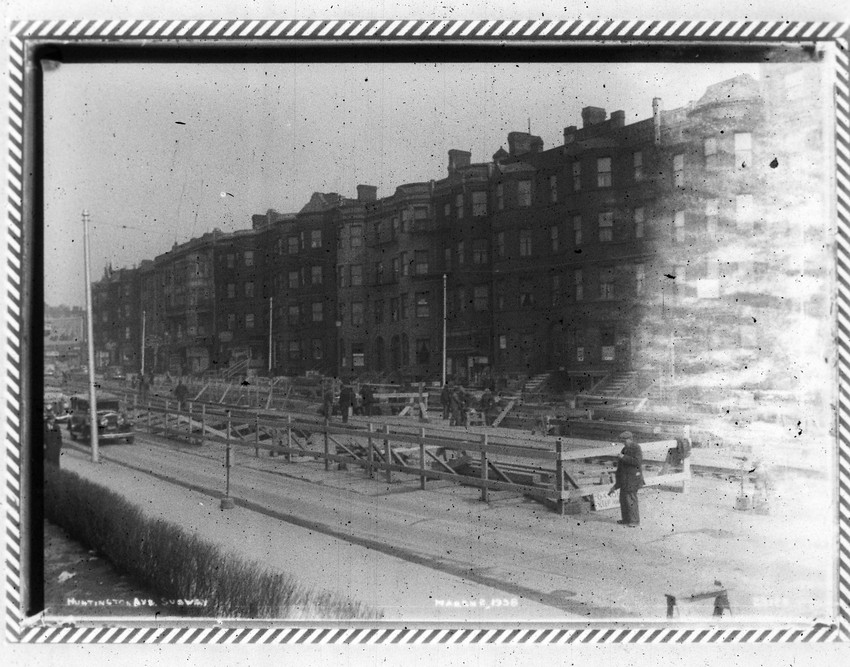

Huntington Avenue Subway under construction.

Another view of Huntington Avenue Subway construction.

Note: learn more about how the Boylston and Tremont Street Subways and their extensions were constructed in "Subway."

By the mid-1940s, Boston's transit infrastructure was exhausted and in dire need of renovation or replacement. Due to lack of maintenance during World War Two, when many transit workers were fighting the war, most surface streetcar lines were barely functioning, and many streetcars with falling apart. It was clear that something had to be done to bring Boston's transit infrastructure into the postwar age. Many streetcar lines' streetcars were replaced with trackless trolleys around this time rather than repair tracks; however, this meant that a good number of dedicated streetcar reservations were no longer used, meaning that transit was now in many places forced to mix in with general traffic. Therefore, in 1945, leading Boston Elevated Railway officials convened to discuss what to do to modernize and streamline Boston transit.

The convention came to the conclusion that what had to be done was extend rapid transit links within and in the suburbs of Boston:

The convention came to the conclusion that what had to be done was extend rapid transit links within and in the suburbs of Boston:

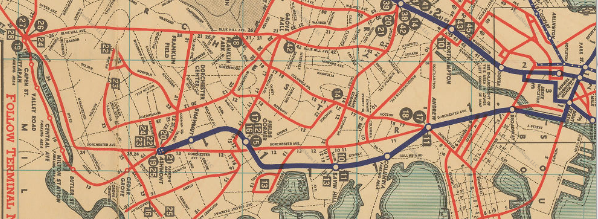

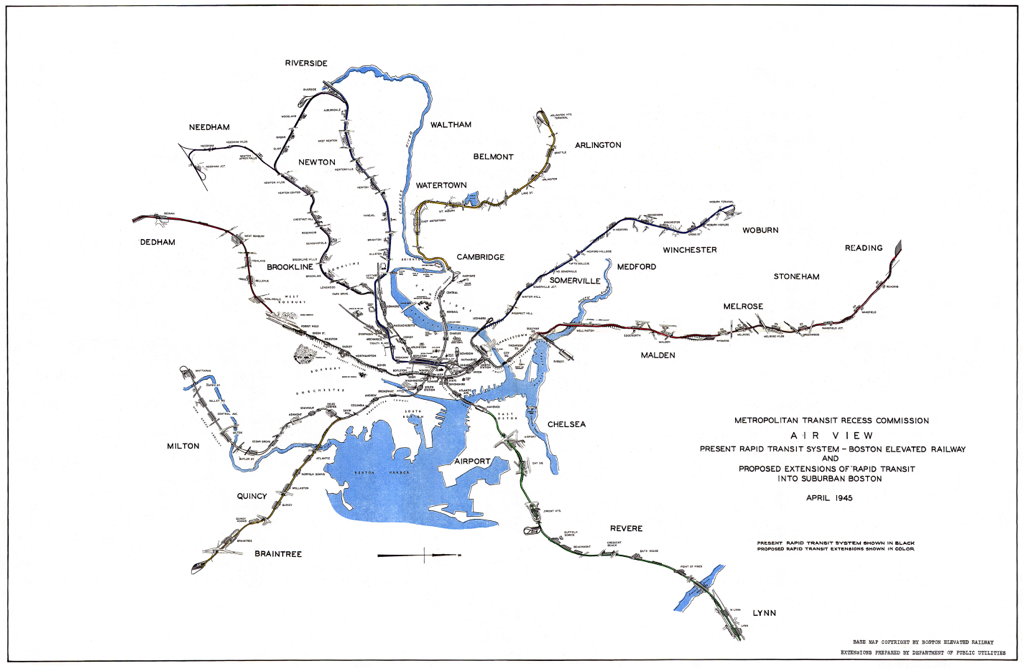

1945 BERy map showing the proposed rapid transit extensions to be built in the near future.

To zoom into the map and see the proposed extensions in relation to then-existing infrastructure, visit the following link: http://www.wardmaps.com/viewasset.php?aid=9801

The extensions proposed in 1945 were the following, clockwise from map center:

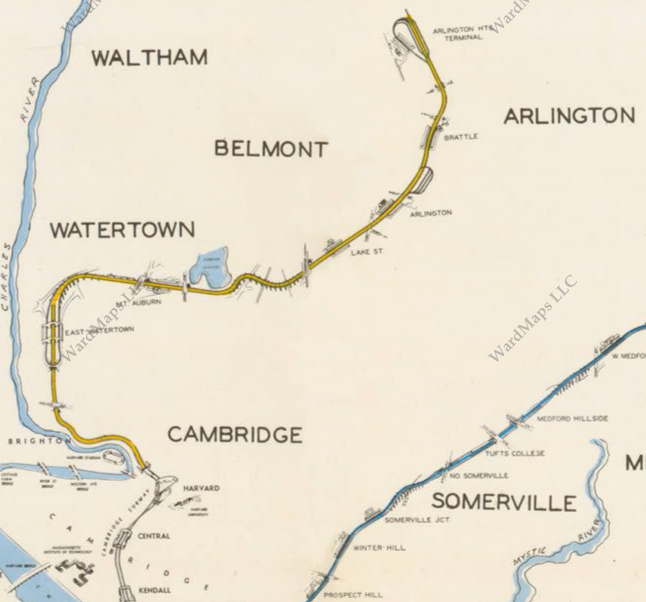

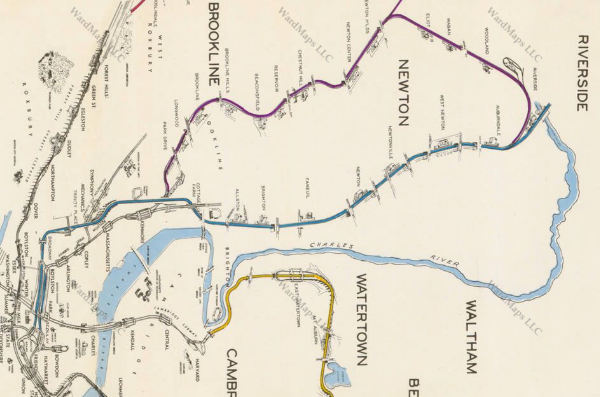

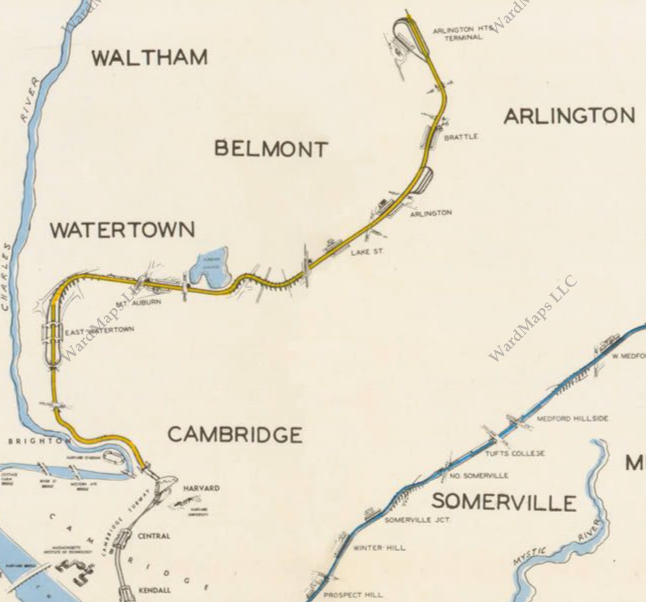

1) Extension of Cambridge-Dorchester Rapid Transit (Red Line) from Harvard to Arlington Heights via Watertown:

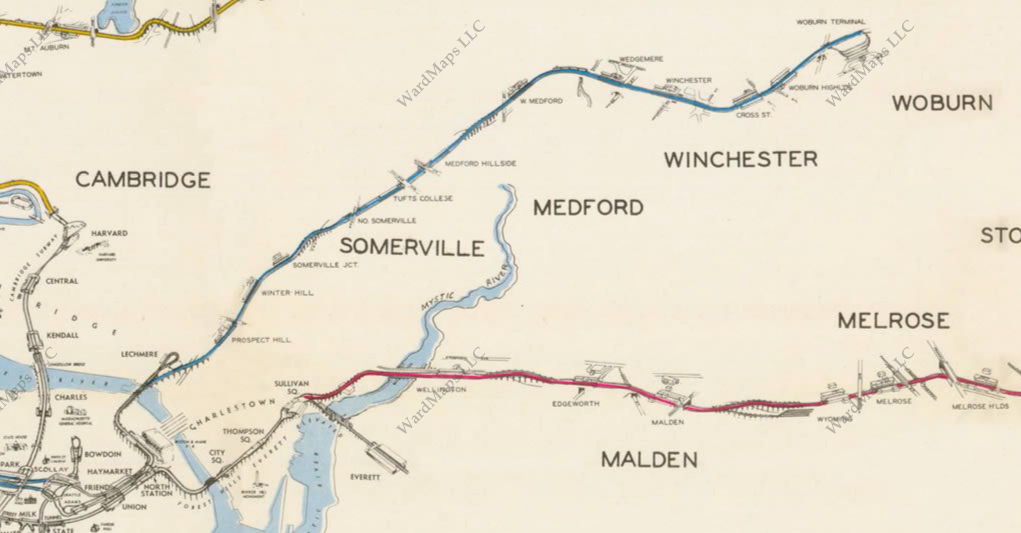

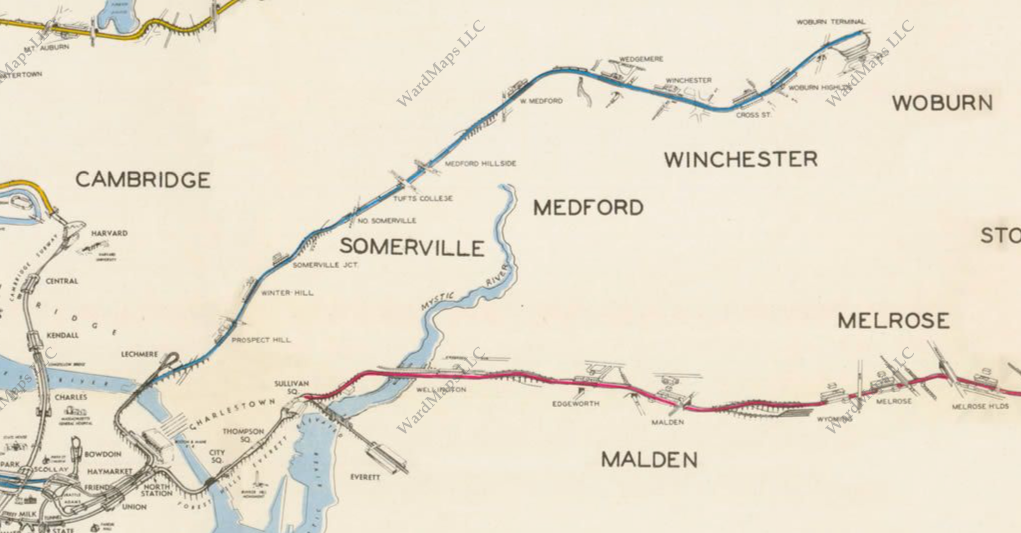

2) Extension of streetcar ROW through downtown (Green Line) from Lechmere Station to Woburn via Somerville, Medford and Winchester:

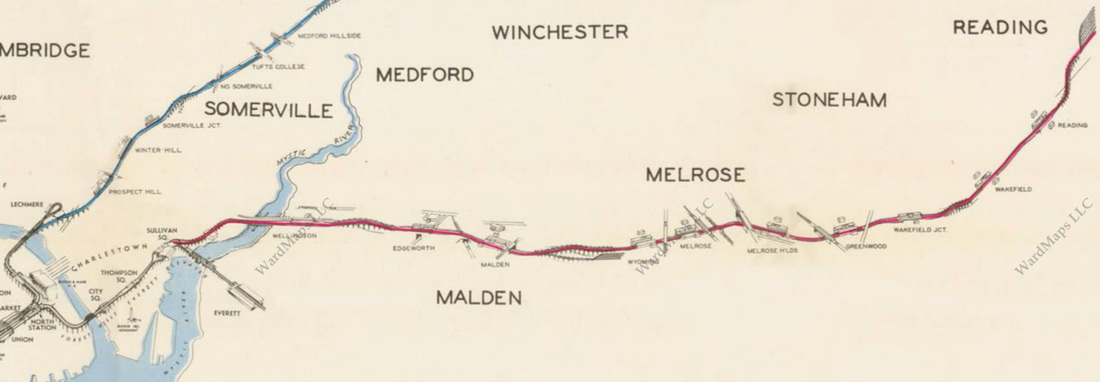

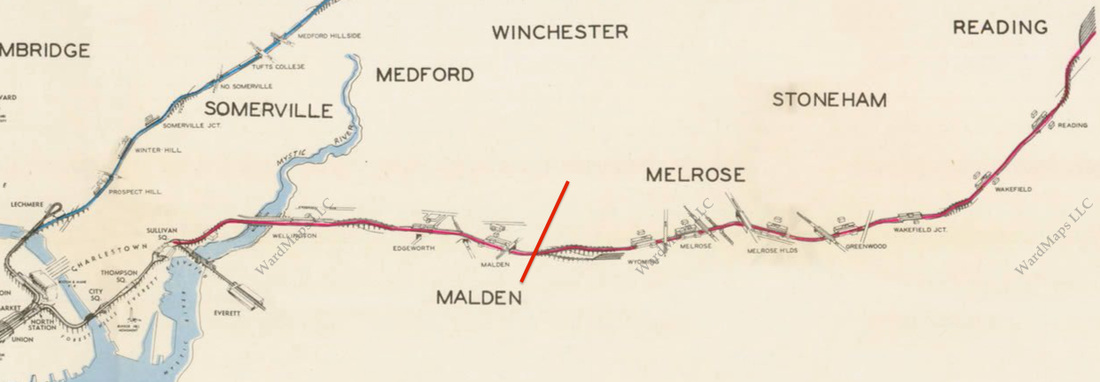

3) Extension of the Charlestown Elevated (Orange Line) from Sullivan Square to Reading via Malden, Melrose and Stoneham:

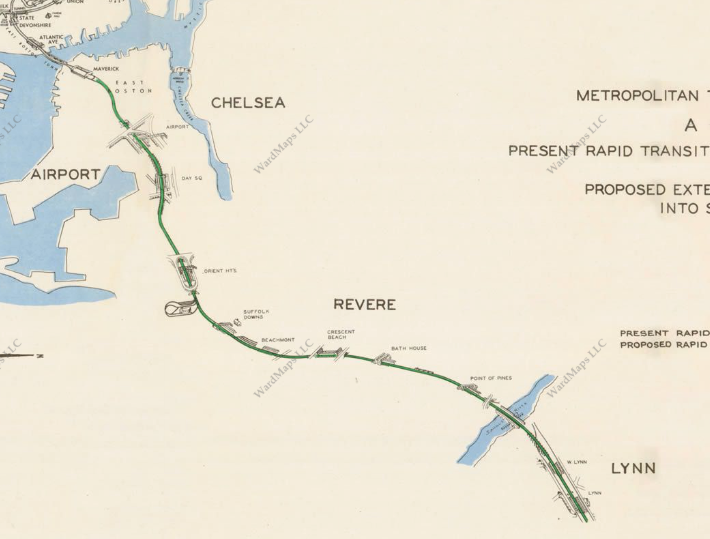

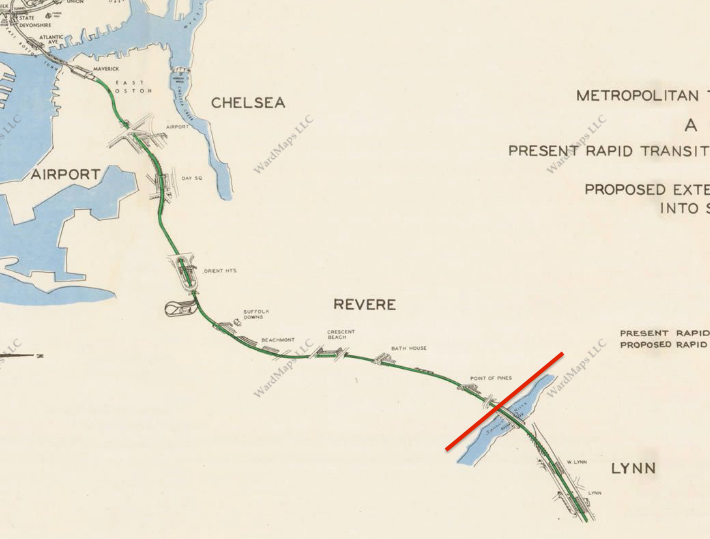

4) Extension of the East Boston Tunnel/ROW (Blue Line) from Maverick Square to Lynn via Logan Airport and Revere:

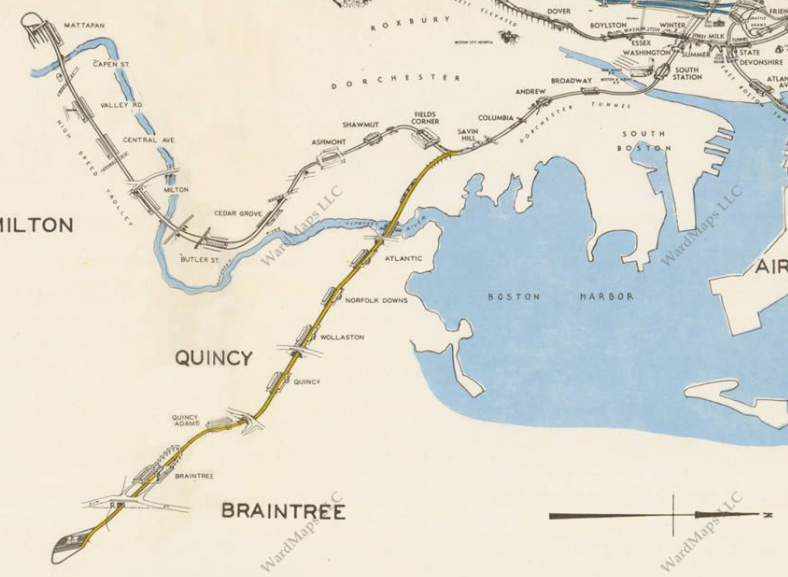

5) Construction of a rapid transit line to Braintree via Quincy branching off of the Cambridge-Dorchester Rapid Transit line (Red Line) after Savin Hill Station:

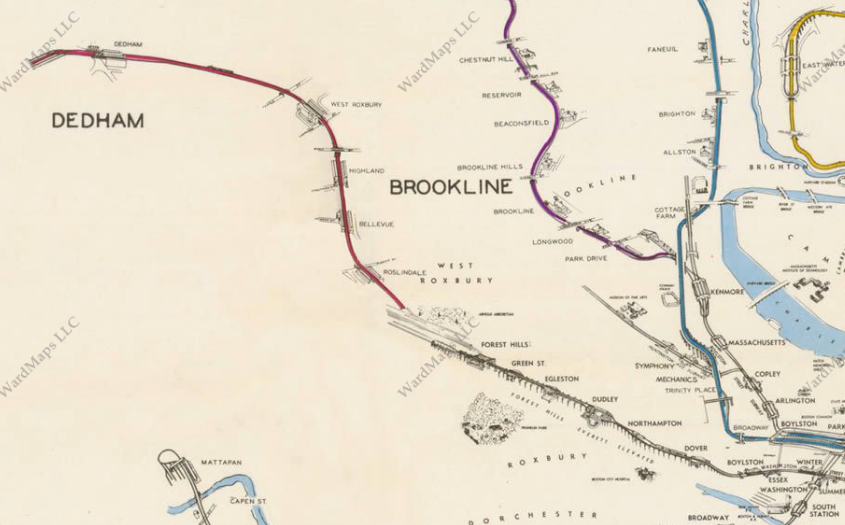

6) Extension of the Washington Street Elevated (Orange Line) from Forest Hills to Dedham via Roslindale and West Roxbury:

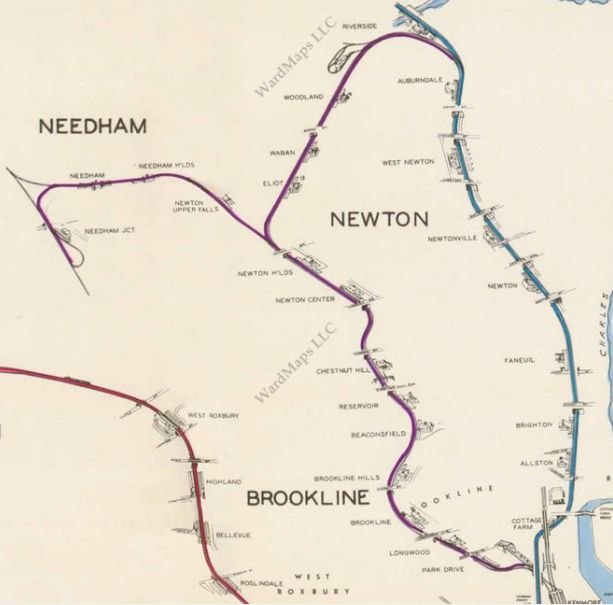

7) Construction of a rapid transit line branching off of the Boylston Street Tunnel after Kenmore Station running through Brookline and Newton then splitting into two branches:

a) To Riverside in Newton

b) To Needham Junction

a) To Riverside in Newton

b) To Needham Junction

8) Construction of a rapid transit line running from Scollay Square to Riverside in Newton via Brookline, Brighton and Newton:

Ultimately, all of these proposed extensions were or are being built in some form. First to come was the Revere Extension of the East Boston Tunnel ROW along the old Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad ROW to Wonderland Station in Revere. (Note: The East Boston Tunnel was converted from streetcar to rapid transit in 1925) The extension opened in 1954; however, it is important to note that it was not built all the way to Lynn as initially proposed, due to budget constraints:

Red line shows the extent to which the extension was built; two stations in Lynn were never built.

The proposal to extend the ROW, now re-designated the Blue Line, to Lynn has resurfaced in recent years, though it is unlikely to be built:

http://www.massdot.state.ma.us/Portals/0/docs/infoCenter/boards_committees/PublicPrivate/BlueLineExtP3ScreeningRpt.pdf

http://www.massdot.state.ma.us/Portals/0/docs/infoCenter/boards_committees/PublicPrivate/BlueLineExtP3ScreeningRpt.pdf

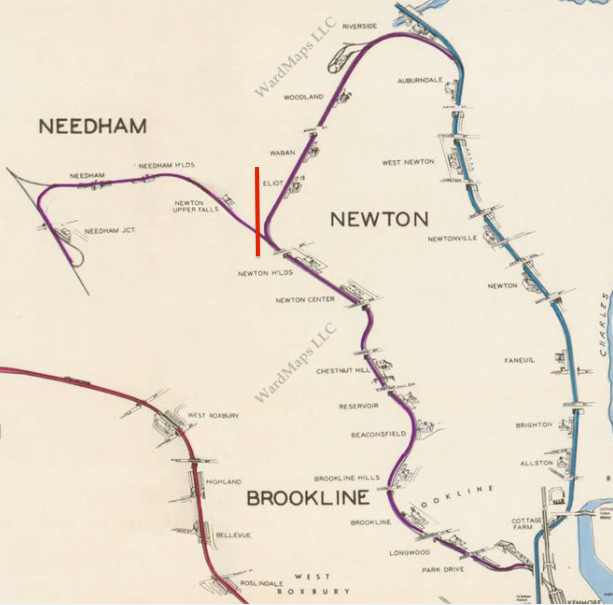

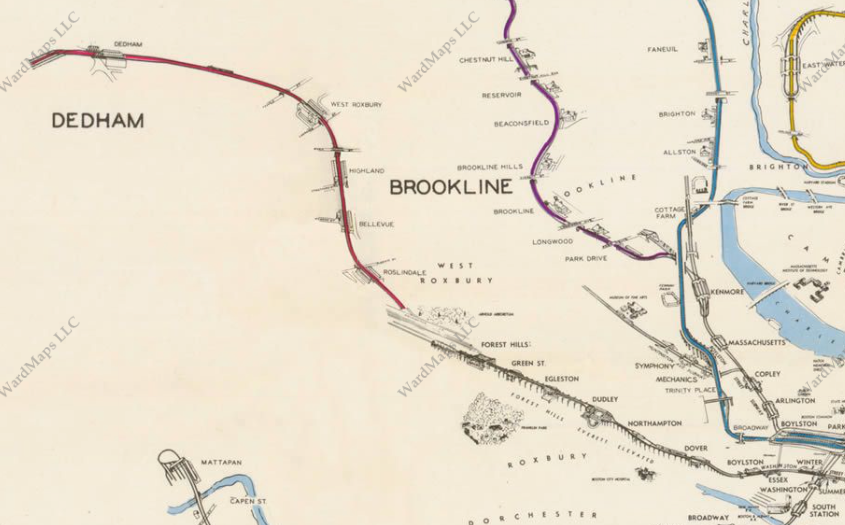

Next to come was what is now the D Branch of the Green Line—the construction of a high-speed streetcar line from Kenmore to Riverside via the former Highland Branch ROW of the Boston and Albany Railroad. Again, the extension was not built to its entirety—the second line to Needham was never built due to budget constraints. The ROW to Needham remains and may be made a "rail-trail" bike path in the near future.

To left of the red line is the Needham Spur, which was not constructed.

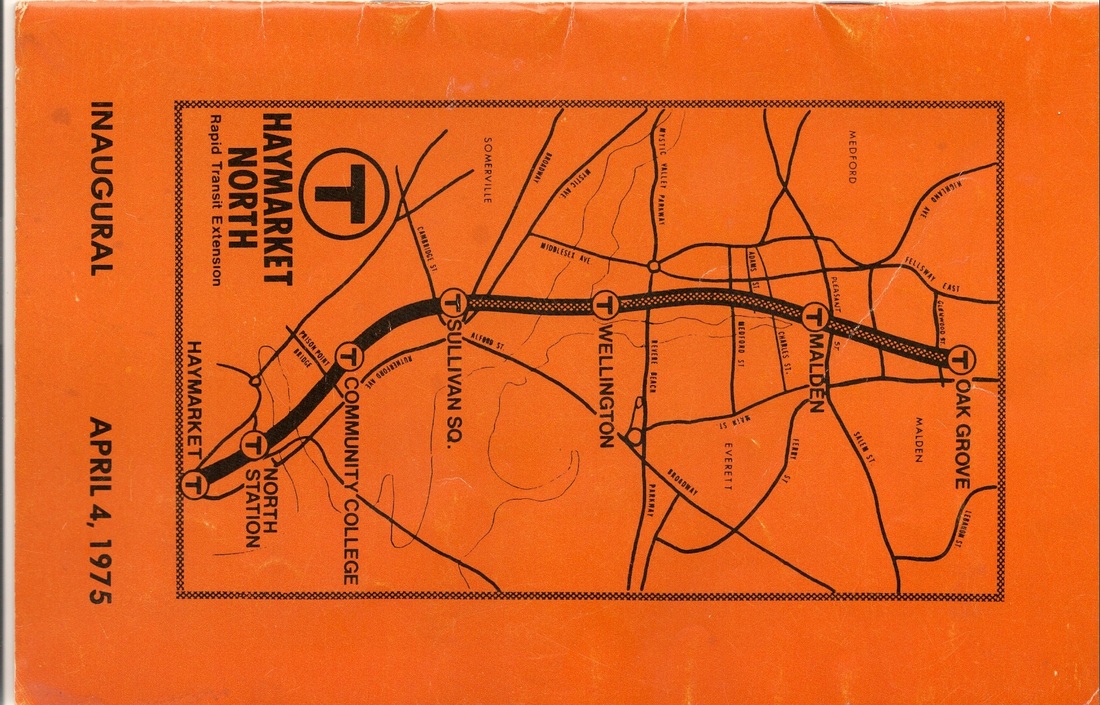

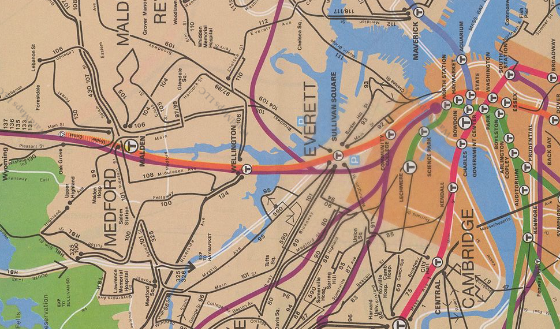

The last pre-1980 extension to be built was the Haymarket North Extension, which brought the Orange Line under the Charles River along a new right-of-way to Charlestown and Malden, though not to Reading as originally proposed. An express track between North Station and Wellington Station remains unused to this day, built to provide express service from Reading to Boston in case of an Orange Line extension to Reading .

Original 1945 proposal to extend the Orange Line to Reading, though not to build the new ROW through Charlestown. Red line shows how far the Orange Line was ultimately extended.

1975 inaugural brochure for the Haymarket North Extension. Every new station opened in 1975 except for Oak Grove, which opened in 1977.

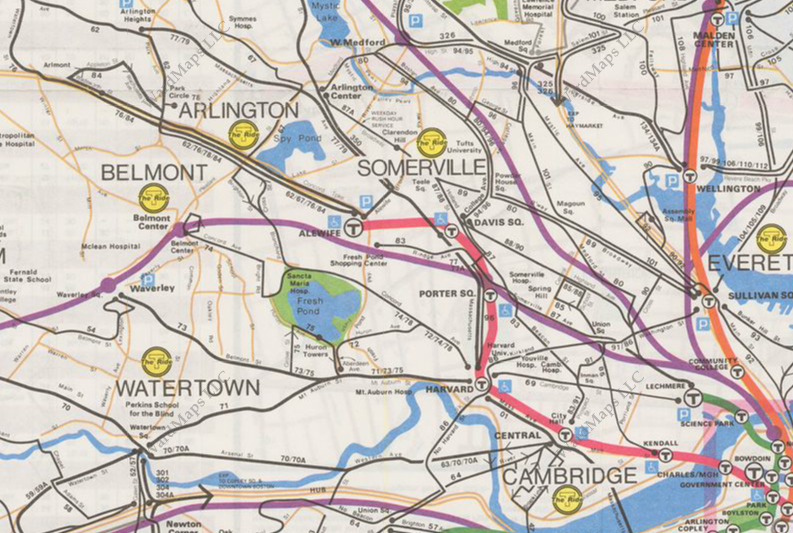

1976 MBTA map showing the new Orange Line to Malden, with the section to Oak Grove labeled as "under construction."

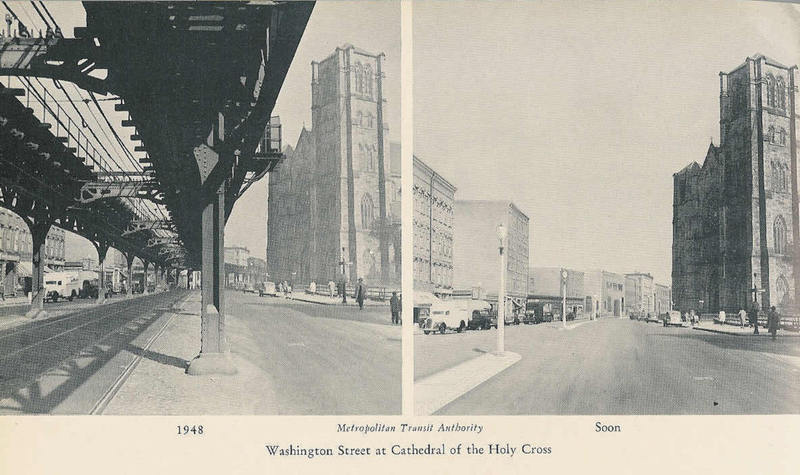

One transit project that was not reflected on the 1945 proposals map was the eventual replacement of the Washington Street Elevated. By 1945, the El was 44 years old and beginning to fall into bad shape. Wartime constraints aside, the El cast a dark shadow on the street below and left much of the South End, Roxbury and Jamaica Plain in the dark. Accordingly, it was clear that a replacement for the El would have to be built in due course. Origninally, it was thought to build a Washington Street Subway to replace the El—the Greater Boston Development Committee's 1948 report "Surging Cities" states that the El would be removed and a subway constructed in its place, and that "the 1948 Legislature authorized $19,000,000 for extension of the Washington Street Tunnel to a point near Cedar Street, Roxbury and for tearing down a long section of the Washington Street El" and listed the project as one that should be "given first attention." But as urban renewal began to hit Boston, a new idea came to transit planners' minds.

Image from Surging Cities, a 1948 Greater Boston Development Committee report with plans for Boston's future, showing the proposal to bury the Washington Street Elevated and run rapid transit underneath the street.

After World War Two, many roads were in bad shape. Additionally, many more cars travelled through Boston than had in the past. The answer: build superhighways throughout the city that would speed up traffic flow and be able to accommodate tens of thousands of additional cars. Between 1950 and 1970, I-90, I-93, 128 and the Central Artery were all built in the Boston Area.

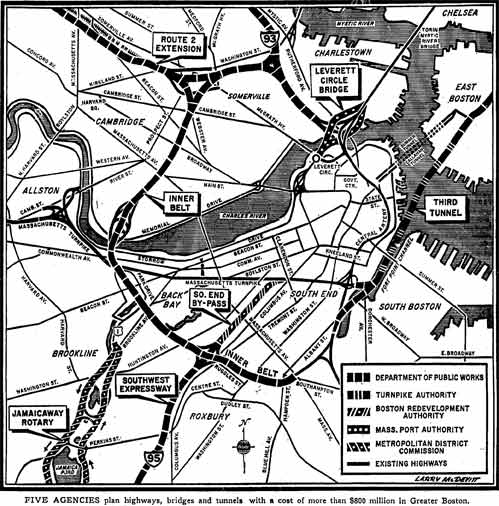

1969 Boston Globe map showing the highways planned to be built throughout Boston over the coming years.

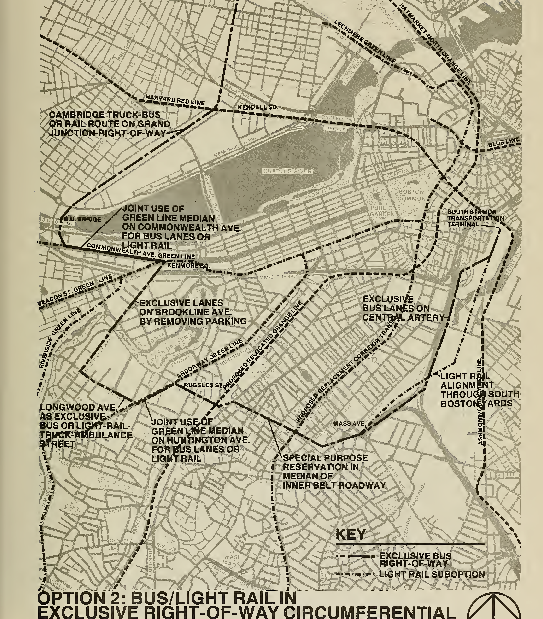

One of the highways proposed to be constructed was a routing of I-95 from Canton to downtown Boston through Jamaica Plain and Roxbury. It was thought that, rather than just route the Orange Line through a new Washington Street Subway, the Orange Line could be rerouted into the median of I-95, in addition to or instead of a Washington Street Subway or surface rapid transit ROW which, if built, would use streetcars and would connect to the Pleasant Street Portal.

1972 Boston Transit Planning Review report showing proposed rapid transit constructions. Along the planned I-95 ROW is the "Proposed Relocated Orange Line, and along the Washington Street Corridor is "Proposed Replacement Corridor Transit," with a dotted line showing a "Light Rail Suboption."

Also worth noting on the map above are the proposed "Special Purpose Reservation in Median of Inner Belt Roadway," similar to the bus lane proposed for Melnea Cass Boulevard today, and a plan that never came to fruition to designate "Longwood Avenue As an Exclusive Bus or Light Rail—Truck—Ambulance Street." If implemented today, the Longwood Avenue plan would significantly alleviate traffic in the Medical Area!

Ultimately, I-95 was never built through Boston due to community opposition, instead being routed along 128 out west (more on Boston's cancelled highway projects in "Boston's Cancelled Highways"). However, the land for the new highway had already been cleared, leaving Boston with acres of space in need of a function. The anticipated I-95 right-of-way became Southwest Corridor Park in Jamaica Plain and Roxbury, as well as a new right-of-way for the Orange Line.

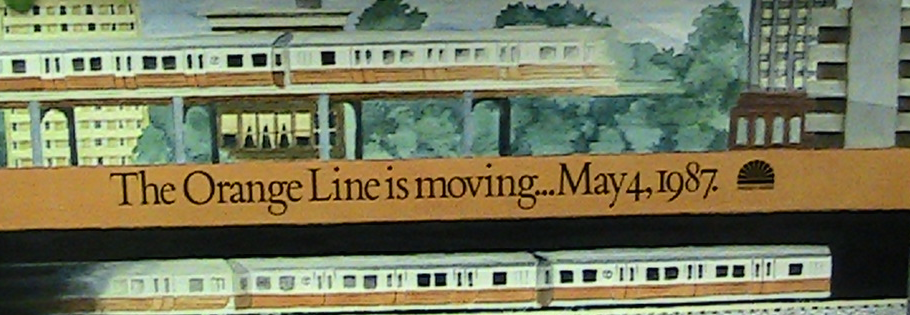

Poster announcing the moving of the Orange Line to its new right of way, the Southwest Corridor.

While it was proposed in 1945 to extend the Orange Line to Dedham from Forest Hills, and later even considered to extend the line further to Needham, the extension was not built along with the new Orange Line.

1945 proposed extensions map showing the proposed extension of the Orange Line (then the El) to Dedham from Forest Hills Station.

As for the Washington Street Corridor, it took 15 years from when the El ended service in 1987 to the opening of the new Silver Line Washington Street in 2002 for a replacement rapid transit line to be built. The Silver Line did not replace the entire El; it only runs from downtown to Dudley Square, as the new Orange Line is relatively near the area of Washington Street between Egleston Square and Forest Hills, the terminus of the both the El and the new Line. The Silver Line is not a streetcar line as originally proposed; rather, it is a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) line with dedicated lanes along Washington Street.

A Silver Line bus along Washington Street in the South End running along its dedicated lane. Image copyright Steve Pinkus/In Transition Magazine

After the removal of the Washington Street Elevated, there was one El left in Boston, the Green Line's Causeway Street Elevated. In 2004, the Causeway Street Elevated was torn down and a new subway opened, putting North Station underground and bringing Green Line trains to the Lechmere Viaduct, the last elevated railway section in Boston, underground.

The old elevated North Station on Causeway Street, the last elevated station in Boston over a street. Image copyright oldtrails.com

The head house for the new underground North Station for the Green Line, located right next to the old elevated station and a level up from the underground North Station for the Orange Line that opened in 1975. Image copyright CNN.

In addition to proposing the unbuilt Washington Street Subway, Surging Cities also listed the extension of the Cambridge-Dorchester Rapid Transit ROW to both Braintree and "a point near Porter Square" as requiring "first attention." Ultimately, both of these extensions came to fruition. In 1971, the South Shore Extension of the Red Line opened, splitting off of the Cambridge-Dorchester ROW by JFK/UMASS Station and running until Quincy Center along the former Old Colony Railroad ROW. Later, in 1980, the second section of the extension opened, bringing the line further south along the Old Colony to Braintree. It is rumored that it was once thought to extend the Red Line further south all the way to Brockton!

Note: Excepts of Surging Cities can be seen here: http://bostonhistory.typepad.com/notes_on_the_urban_condit/2006/08/how_soon_is_now.html

1945 proposed extensions map showing the Braintree Extension.

In 1984, the first section of the Northwest Extension of the Red Line opened, bringing the line all the way to Davis Square in Somerville. The extension was completed in 1985 with the opening of Alewife Station in East Cambridge. The route taken through Somerville was different from the originally intended route, shown below, which had the extension running through Watertown and Fresh Pond along the Watertown Branch Railroad before joining the Boston and Maine Railroad ROW by Alewife Brook and continuing to Arlington Heights. The train that was ultimately built required its own deep bore tunnel to reach Davis Square and runs under the old Boston and Maine Railroad ROW between Davis Square and Alewife. The extension to Arlington Heights was never built; the Boston and Maine Railroad ROW between Alewife and Arlington Heights was made into the Minuteman Bikeway.

1945 proposed extensions map showing the proposed extension of the Cambridge—Dorchester Rapid Transit (Red Line) to Arlington Heights via the Watertown Branch Railroad.

1988 MBTA map showing what was ultimately constructed—the Red Line as we know it today from Harvard to Alewife.

Subway grates just outside of Alewife Station along the Minuteman Bikeway covering the short tunnel extension built 50-100 meters down the Bikeway in case the Red Line is ever extended to Arlington Heights.

The new Orange Line along the Southwest Corridor, which opened in 1987, was the last rail rapid transit extension constructed in Boston. The Silver Line Bus Rapid Transit line, as previously mentioned, opened along Washington Street in 2002, replacing the Washington Street Elevated; in 2004, a second branch of the Silver Line, the South Boston Transitway, opened between South Station and the Seaport/Innovation District. The Transitway uses dual-mode trackless trolleys and runs in a dedicated tunnel.

Dual-mode Silver Line trackless trolley in the South Boston Transitway at Silver Line Way Station. Image courtesy Flickr User Utahbeach.

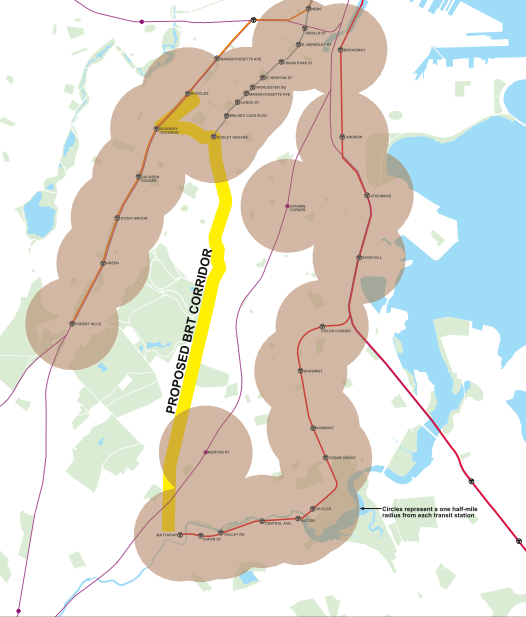

It was also seriously considered to extend the Silver Line to Mattapan Square, or alternatively to build a bus rapid transit corridor along Blue Hill Avenue for a new 28X bus route, but these plans never came to fruition due to community opposition.

Map showing the proposed Blue Hill Avenue bus rapid transit right-of-way. Image courtesy The Transport Politic.

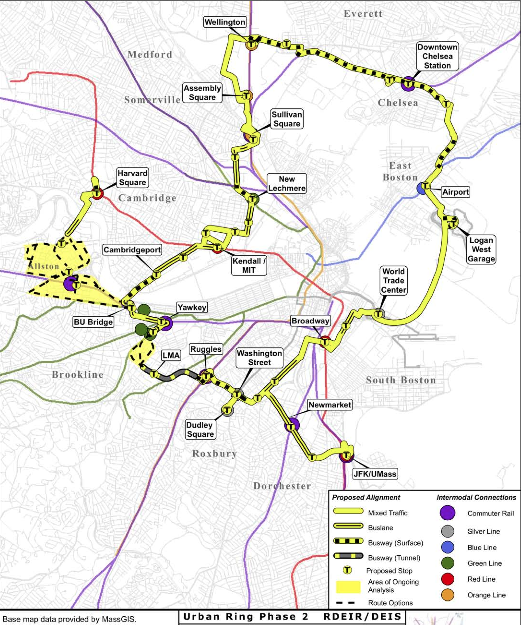

The Blue Hill Avenue BRT corridor is not the first proposed Boston BRT project to be shelved in recent years. In 2010, the Urban Ring BRT Project was shelved due to lack of funding. The Urban Ring would run in a circle around Boston along surface right-of-ways and through a dedicated tunnel in the Longwood Medical Area, thereby bringing rapid transit to a large portion of the city and, particularly in the LMA, addressing longstanding traffic problems.

Official MassDOT map of the proposed Urban Ring, including the LMA tunnel. See the map with higher resolution at http://www.massdot.state.ma.us/theurbanring/images/LPA_Figure.pdf.

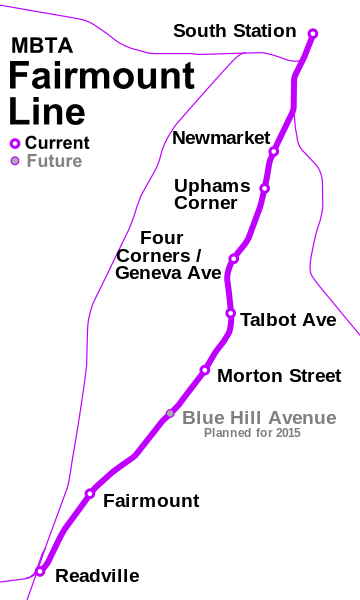

However, there are a good number of transit projects in Boston under construction in Boston currently and one that is almost complete. Between 2012 and 2013, three new stations opened along the new upgraded Fairmount Commuter Rail Line through Dorchester and Mattapan, aiming to make the line more akin to a rapid transit line and provide Dorchester and Mattapan with more rapid transit options. Fares have been lowered to subway rates, and the commuter rail trains will soon be replaced with diesel multiple-units to provide quicker multi-stop service.

The Fairmount Line. Talbot Avenue Station opened in November 2012, and Four Corners/Geneva and Newmarket in July 2013. A fourth new station by Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan is planned for 2015. Map courtesy Wikipedia User Pi.1415926535.

Today, there are three transit projects currently under construction. First is the new Assembly Square infill station along the Orange Line's Haymarket North Extension, which is set to open in 2014 and will provide the Assembly Square district of Somerville, which has been undergoing redevelopment in recent years, direct Orange Line access after almost 40 years of being bypassed by Orange Line trains.

An Orange Line train passes the under-construction Assembly Square Station, with some of the new development in the area visible in the background.

Second is the Green Line Extension. Set to open around 2020, the Extension is a currently-under-construction rapid transit line that will bring Green Line trains further north all the way to Tufts University/College Avenue in Medford and along an additional line to Union Square in Somerville. The Green Line Extension was originally proposed in 1945; 75 years later, it will be built and operational.

1945 proposed extensions map showing the proposed Green Line Extension running to Woburn from a new relocated Lechmere Station, via Somerville, Medford and Winchester. Right now, the extension will only be built until Tufts University, with a possible later extension further into Medford and a separate spur to Union Square in Somerville not previously proposed:

MBTA map showing the stations that will be built along the new Green Line Extension, with the last station by Route 16 "on hold."

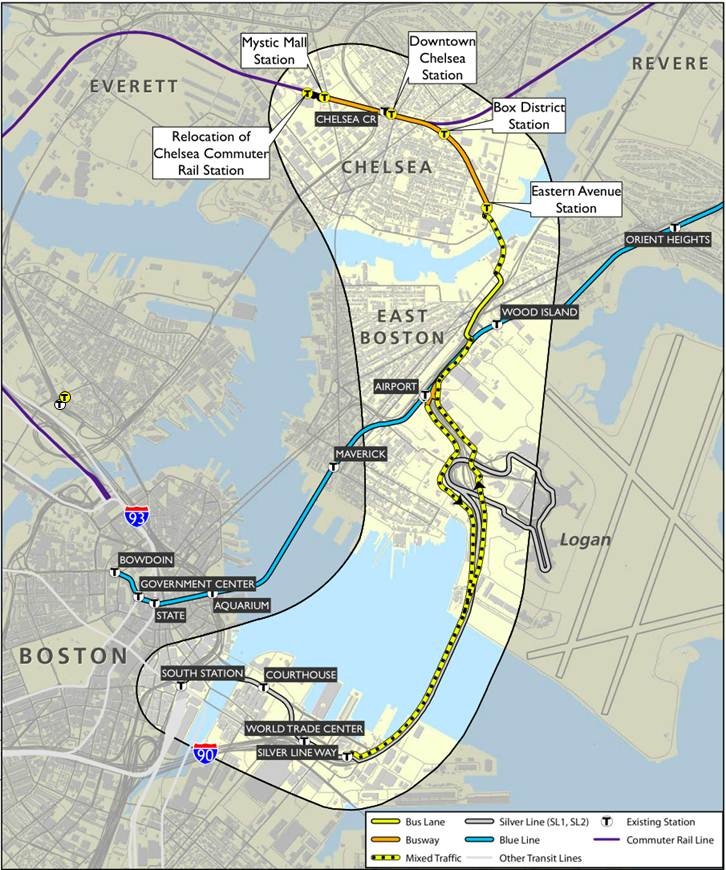

Third is the extension of the Silver Line from Logan Airport to Chelsea. Currently under construction, the Silver Line Extension will bring bus rapid transit to a route along a section of the old Grand Junction Railroad originally proposed to be part of the Urban Ring (more on the Grand Junction Railroad and Silver Line Extension at "Grand Junction Railroad").

MassDOT map of the Silver Line Extension.

It is amazing to think about what the Boston transit system will look 50 years, 25 years—even 10 years from now. Exciting new extensions are already planned to take shape in Boston within the next 10 years:

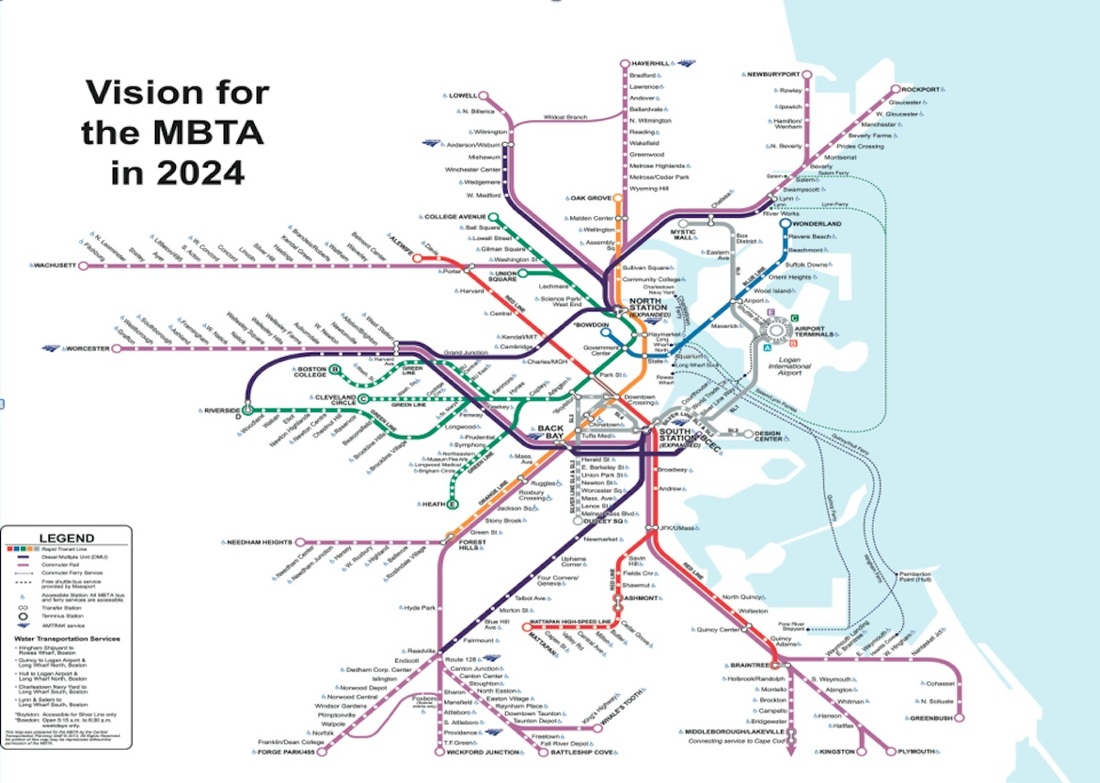

The map above was released early in 2014 by the MBTA showing the vision for service in 2024—effectively, this is the next incarnation of the 1945 proposed extensions map. The proposed extensions here include:

—Silver Line from South Station to Chelsea via Logan Airport

—Green Line Extension

—New Indigo Line with the following branches, clockwise:

—Green Line Extension

—New Indigo Line with the following branches, clockwise:

- North Station—Woburn via Medford-Woburn railroad ROW originally proposed for Green Line Extension

- North Station—Lynn via Chelsea, effectively substituting for Blue Line Extension to Lynn

- South Station--Readville/Hyde Park via Mattapan/Dorchester along current Fairmount Commuter Rail Line ROW

- South Station—Riverside via Brighton and Back Bay Station, a route originally proposed in 1945

- Back Bay Station—Innovation District

- North Station—West Station (Allston/Brighton) via Cambridge/Grand Junction Railroad ROW

The new Indigo Line will use new self-propelled diesel trains, diesel multiple-units, and will serve stretches of the MBTA's commuter rail system that are more local to Boston and through which commuter trains currently pass without stopping. In the case of the Grand Junction branch, it will be bringing service back to a route that rarely sees commercial service and has never been used for passenger service before. Many of these routes capitalize upon the changing face of Boston, as the relevance of certain sections of the city, for instance Kendall Square/MIT and the Innovation District, continues to increase. The Innovation District, as well as the area of Allston/Brighton around the proposed West Station, are also areas where new transit-oriented development (TOD) could take place in the future if adequate rapid transit is built there. It will be very interesting to see how Boston's coming transit extensions affect the future development of the city!

[Edit: On 5/27/14, news broke that West Station has been put on hold, signaling an indefinite future for part of the Indigo Line: http://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2014/05/26/plans-include-proposed-west-station-turnpike-reconstruction-project-massdot-officials-say/EjVjeYpRkbTVTMyfgoYOiP/story.html]