The West End's Transformation

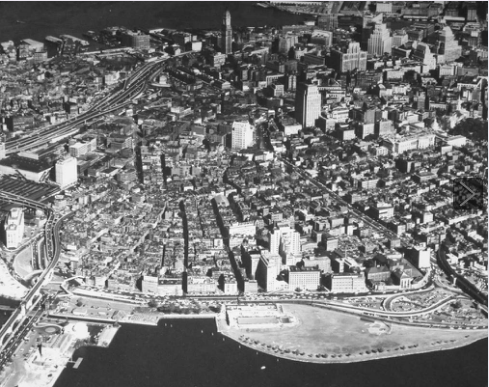

The West End in the 1930s. To orient you, the train tracks lead out of North Station, and this picture looks towards the Harbor. Image courtesy Cyburbia.

It's a normal day. You just left Storrow Drive, and now you're passing on the ramp by the TD Garden, about to enter I-93 North or Route 1. Look around you. Imagine that all of the land you are driving over, and that you just drove under, was occupied by tenements and small shops. People live here, and commerce is bustling throughout the various storefronts under the apartments.

All of this bustle ended in the late 1950s, when the West End was completely razed to make way for an "urban renewal" project that replaced all of the West End's homes and stores with superblocks of luxury towers and highways. Here's a view of the West End before demolition:

Image (and the next one below) courtesy Lowery Aerial Photos/West End Museum

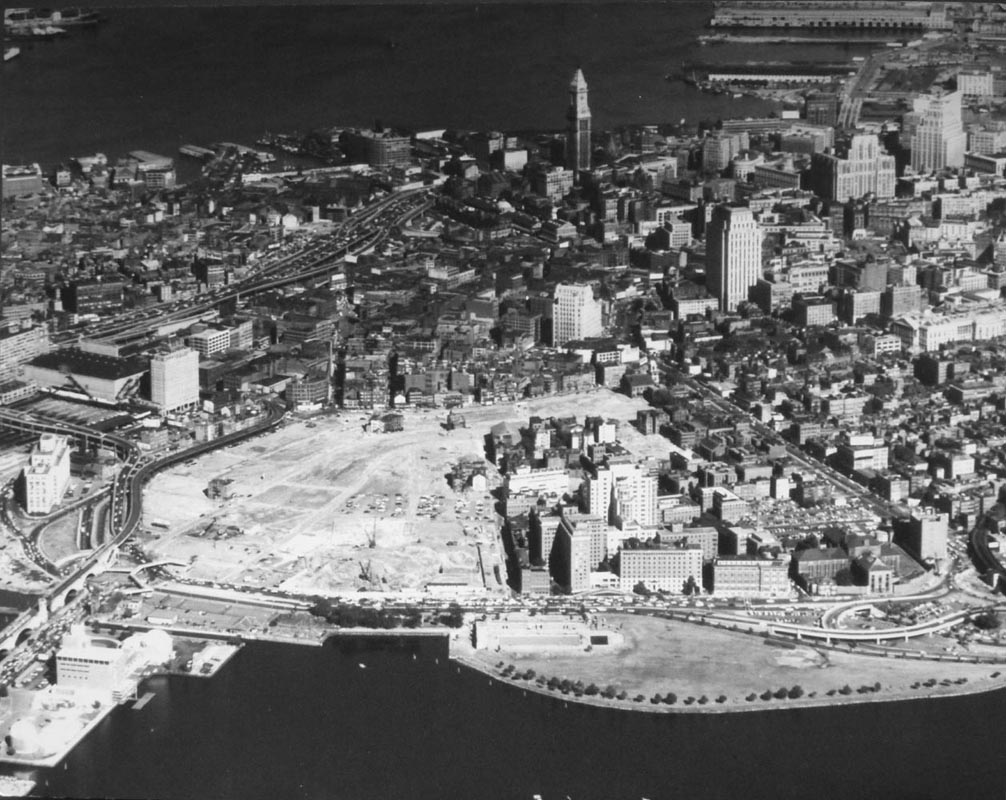

And after demolition:

Sure looks different afterwards, doesn't it?

This photo (and the one above it) looks onto the West End from across the Charles River, near the Cambridgeside Galleria. The viaduct on the bottom left corner is the Lechmere Viaduct the Green Line uses today. As the photo shows, everything on the other side of the Causeway Street Elevated from North Station has been demolished, all along Storrow Drive up until the MGH/Mass Eye and Ear complex. Scollay Square still exists in this photo; that will come down shortly afterwards.

This photo (and the one above it) looks onto the West End from across the Charles River, near the Cambridgeside Galleria. The viaduct on the bottom left corner is the Lechmere Viaduct the Green Line uses today. As the photo shows, everything on the other side of the Causeway Street Elevated from North Station has been demolished, all along Storrow Drive up until the MGH/Mass Eye and Ear complex. Scollay Square still exists in this photo; that will come down shortly afterwards.

The West End's brick apartments and neighborhood stores were replaced with "superblocks" lined with luxury high-rises. To this day, there are virtually no businesses in the new West End, other than a few medical offices. Rather than a destination, the new West End feels more like an oasis. People live in the West End, but virtually no one from outside the neighborhood comes in, largely because there is no reason to. As opposed to the bustling center the West End once was, today the West End is a very quiet, largely ignored section of Boston.

The photos in the slideshow below bear witness to the West End's former bustle. All images courtesy Boston Public Library:

These photos show the West End today:

While the West End was a heavily utilized commercial center that thousands of Bostonians called home, many outsiders did not view the West End as favorably as its residents and customers. Politicians and upper-class Bostonians generally viewed the West End as a slum, despite its residents not viewing it as such, which ultimately led to the neighborhood's razing. In general, the West End's residents were happy to live there, and when it was decreed that the West End would be razed a vast majority of residents unsuccessfully protested for the plans to be abandoned. However, Boston's government had spoken, and thus the West End met its end. Once Mayor John B. Hynes and the Boston Redevelopment Authority had a plan, there was no way of stopping it.

The Hynes Administration founded the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1957, at a time when the city was very run down. During World War Two, as I have discussed in other articles, city infrastructure did not receive its necessary maintenance because virtually all workers were soldiers in the war. Therefore, buildings and roads began to show significant wear and tear, to the point that city officials concluded it would make more sense to simply start over with new rather than restore old.

Under such a mentality, the city officials perceived the West End, a lower-class neighborhood with aging buildings, as a relic of old Boston that had to be replaced with new, better developments. Therefore, Mayor Hynes and the Redevelopment Authority sought to replace all of the West End's old homes with new, "better" ones. Ironically, the apartments, which were mostly occupied by working-class individuals, were replaced with luxury towers rather than more affordable units, thereby displacing thousands of residents who could not afford the new homes that replaced their old ones.

At least the West End was replaced with new homes. Other Boston Redevelopment Authority projects of the era obliterated perfectly good commercial and residential districts and replaced them with developments that served completely different purposes. Shortly before the West End's razing, the Authority razed the "New York Streets" district of the South End, then occupied by brick apartments, to replace it with newer infrastructure. The land became the home of the Boston Herald's printing plant as well as some other industrial facilities:

The Hynes Administration founded the Boston Redevelopment Authority in 1957, at a time when the city was very run down. During World War Two, as I have discussed in other articles, city infrastructure did not receive its necessary maintenance because virtually all workers were soldiers in the war. Therefore, buildings and roads began to show significant wear and tear, to the point that city officials concluded it would make more sense to simply start over with new rather than restore old.

Under such a mentality, the city officials perceived the West End, a lower-class neighborhood with aging buildings, as a relic of old Boston that had to be replaced with new, better developments. Therefore, Mayor Hynes and the Redevelopment Authority sought to replace all of the West End's old homes with new, "better" ones. Ironically, the apartments, which were mostly occupied by working-class individuals, were replaced with luxury towers rather than more affordable units, thereby displacing thousands of residents who could not afford the new homes that replaced their old ones.

At least the West End was replaced with new homes. Other Boston Redevelopment Authority projects of the era obliterated perfectly good commercial and residential districts and replaced them with developments that served completely different purposes. Shortly before the West End's razing, the Authority razed the "New York Streets" district of the South End, then occupied by brick apartments, to replace it with newer infrastructure. The land became the home of the Boston Herald's printing plant as well as some other industrial facilities:

All those factories used to be apartment buildings:

The 1902 Boston map, courtesy of Ward Maps, shows the New York Streets. The streets are a narrow grid that housed its apartments well, in contrast to today's large lots and super blocks in the area as shown by the Google Map. Note the train tracks in the 1902 map, as the streets were named as such because of the Boston & Albany Railroad that ran near them.

Other urban renewal projects of the era showed similar disregard for the original purpose of the areas in which they were conducted. Shortly after the West End's razing, the Boston Redevelopment Authority tore down Scollay Square, a commercial and theatre district of Boston on the edge of the West End, to replace it with a few government buildings. In this case in particular, the extent of the demolition is only fully realized once one sees a "before-after sequence."

The above photo, shown in Streetcar Tracks and courtesy Boston Public Library, shows Scollay Square in the 1940s as a bustling commercial district, with a multitude of shops and other commercial utilities. Today, after the demolition, this is Scollay Square:

A desolate "brick desert," as John Kyper iterates in Streetcar Tracks, with nothing but government buildings.

To be fair, they left a few shops:

To be fair, they left a few shops:

But the amount of commercial buildings that were razed, and the extent of the "desert" that replaced them, is drastic.

The urban renewal projects of the late 1950s and early 1960s are a clear indication of the extent to which Bostonian authority sought change. While run-down sections of Boston could have been restored, the authorities wanted a fresh start following the war with new, sturdy infrastructure to bring in the modern era.

The small section of the West End that has survived until today shows how much potential the old West End's infrastructure had and how possible it would have been to fix what was already there. The "Bulfinch Triangle" district of the West End was spared and has survived to this day. The Triangle is now home to several expensive restaurants and apartments, which goes to show that the West End could have been restored to its pre-World War Two glory without entirely razing the existing infrastructure.

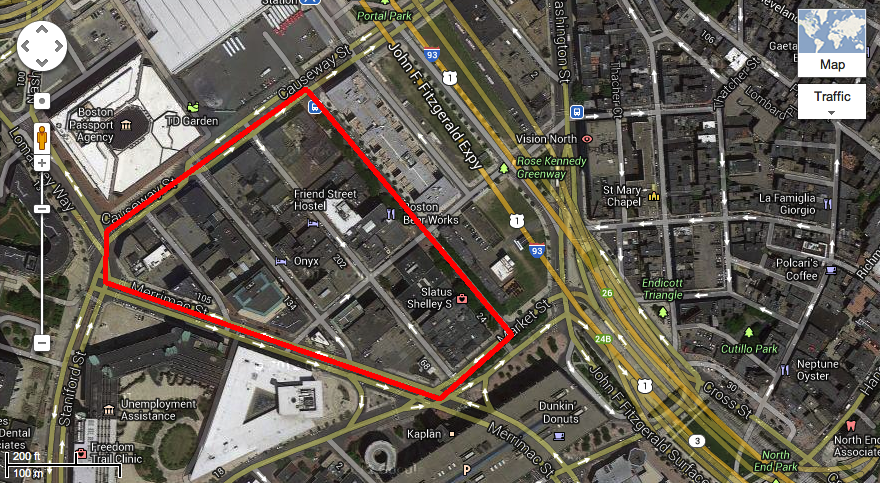

The small section of the West End that has survived until today shows how much potential the old West End's infrastructure had and how possible it would have been to fix what was already there. The "Bulfinch Triangle" district of the West End was spared and has survived to this day. The Triangle is now home to several expensive restaurants and apartments, which goes to show that the West End could have been restored to its pre-World War Two glory without entirely razing the existing infrastructure.

Below is a view of the Bulfinch Triangle, note the architectural similarity to the old photos earlier in this article:

Below is a map showing the area of the Bulfinch Triangle, which is located near the TD Garden and North Station: