Why Are There Still Streetcars in Boston?

After hearing about how many streetcar lines have been eliminated in Boston, one might wonder: "Why are there still streetcar lines running in Boston today?" The answer is simple: they have private right-of-ways that lead to subways.

When the Tremont Street Subway was extended to Kenmore Square in 1932, the Kenmore Portal for the street-running streetcar lines there was sealed and two westerly entrances to the new subway were built. One entrance let 61/C streetcars from Beacon Street into the Subway, and another let 62/B streetcars and 69/A streetcars from Commonwealth Avenue into the Subway. Now, streetcars from Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue no longer had to run on the street to get to downtown. They simply continued along their right-of-ways, which now led to portals that took them to the subway.

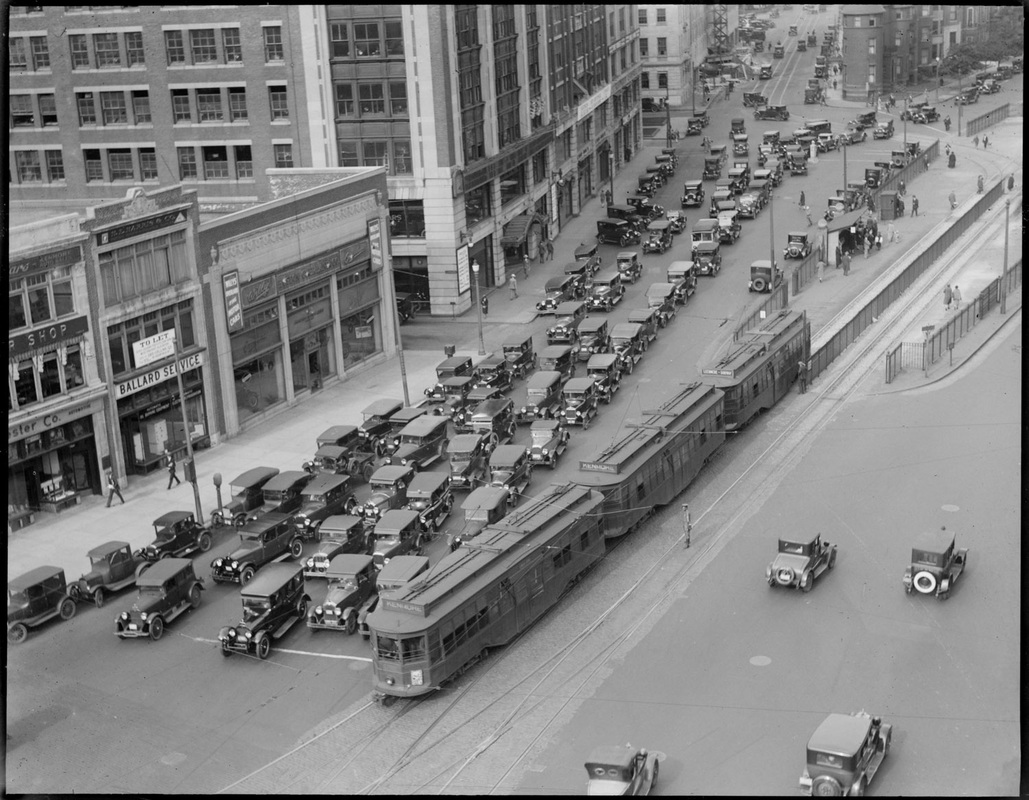

While the routes that later became the A, B and C Lines lived on for at least another 37 years, and even until today, the other routes that ran to Kenmore Square did not last much longer. The street-running streetcar lines that ran through the Kenmore Square area (though not to the actual station) from Brookline Village and Chestnut Hill were immediately replaced with diesel buses. Now that there was a subway in busy Kenmore Square, people no longer wanted to cope with the perceived congestion street-running streetcar operations caused:

When the Tremont Street Subway was extended to Kenmore Square in 1932, the Kenmore Portal for the street-running streetcar lines there was sealed and two westerly entrances to the new subway were built. One entrance let 61/C streetcars from Beacon Street into the Subway, and another let 62/B streetcars and 69/A streetcars from Commonwealth Avenue into the Subway. Now, streetcars from Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue no longer had to run on the street to get to downtown. They simply continued along their right-of-ways, which now led to portals that took them to the subway.

While the routes that later became the A, B and C Lines lived on for at least another 37 years, and even until today, the other routes that ran to Kenmore Square did not last much longer. The street-running streetcar lines that ran through the Kenmore Square area (though not to the actual station) from Brookline Village and Chestnut Hill were immediately replaced with diesel buses. Now that there was a subway in busy Kenmore Square, people no longer wanted to cope with the perceived congestion street-running streetcar operations caused:

Street-running streetcar in Kenmore Square. Photo courtesy Boston Public Library. Note that the tracks curve towards Beacon Street in addition to continuing to the Kenmore Portal, a remnant of when westerly streetcars ran through downtown to reach the subway.

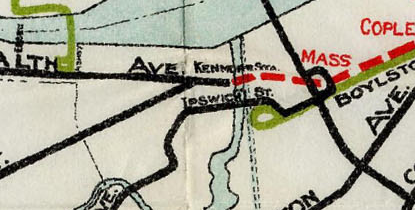

While the only lines that ran to Kenmore Station were the predecessors of the A, B and C Lines, the lines that ran through the area were replaced with buses now that the new subway and underground Kenmore Station were built. 1925 BERy Map.

The construction of a subway along Huntington Avenue for the 39/E Line in 1941 undoubtedly contributed to the E Line's longevity. Now, the E Line did not have to pass through busy Copley Square, as it could simply pass under it. While the 69/A Line still ran along the street for the most part, the 61/C and 62/B Lines, as well as the 39/E Line up to Brigham Circle, could now operate without interrupting car traffic! Not to mention that the Beacon Street, Commonwealth Avenue and Huntington Avenue were, and still are, wide thoroughfares that could accommodate fast-moving cars and a streetcar in the middle.

While other streets, such as Blue Hill Avenue, at one point had dedicated streetcar reservations that still allowed relatively quick traffic flow, no other reservations fed into the subway like those of the 62/B, 61/C and 39/E Lines. Yet more streetcar reservations on streets in places such as East Boston and Somerville prioritized streetcar operation and significantly limited traffic flow,

While other streets, such as Blue Hill Avenue, at one point had dedicated streetcar reservations that still allowed relatively quick traffic flow, no other reservations fed into the subway like those of the 62/B, 61/C and 39/E Lines. Yet more streetcar reservations on streets in places such as East Boston and Somerville prioritized streetcar operation and significantly limited traffic flow,

The streetcar reservation on Bunker Hill Street in Charlestown was part-street running, part dedicated and contained various "speed traps" that gave the streetcar priority and would have undoubtedly irritated Boston's drivers today. Photo courtesy Bradley Clarke of the Boston Street Railway Association (BSRA) and taken from his amazing book "Streetcar Lines of the Hub," a must-read.

Accommodation of traffic flow was key to a line's survival. The first lines to go were the ones that were street-running for their entire operation, such as the lines that once operated in the West End, and did not feed into the subway. These lines simply impeded traffic flow and were, in the eyes of the people, better served by buses or trackless trolleys. Later, as cars became faster, private reservations were demolished to widen roads and allow for faster travel. By 1955, the only lines that remained were either lines, such as the Fellsway Line, that ran along reservations that still allowed for quick travel, or lines, such as the Cambridge lines that fed into the Harvard tunnel, that fed into subways.

Next to go were street-running lines that fed into tunnels. By 1958, all of the Cambridge lines had been eliminated and replaced with more-maneuverable trackless trolleys. The Lenox Street Line was the next to go in 1961; it ran along Tremont Street in street-running form before feeding into the Pleasant Street Portal and entering the subway. Finally, lines such as the Watertown and Arborway Lines, which were only street-running for part of their ways, were eliminated. After 1985, the only street-running line that would last was the E Line to Heath Street, and that was only because it served a significant purpose—shuttling patients to and from the VA Hospital.

Today, we are left with five lines. If they had not run along their own right-of-ways, they would undoubtedly been gone too. There is no way that the B and C would have lasted until today if they still ran through Kenmore Square on street-running tracks. The C Line in particular would have been eliminated in the early 1960s, when the Mass Pike was constructed and the Beacon Street Overpass was constructed to carry traffic across the new highway. The bus that would have "temporarily" replaced the streetcar would have seemed like the simpler long-term transit solution for the corridor. Likewise, the E Line would have been quickly eliminated if it still ran through busy Copley Square on street-running tracks. The Boylston Street Portal through which the line once ran might very well have been sealed and paved over to widen Boylston Street.

That leaves the D and Mattapan Lines. The D Line might never have been constructed in 1959 if the subway under Kenmore Square did not exist for it to feed into and run through to downtown Boston. At most, the D Line would have run to Fenway Station and cut back there, which would have worked well as the line runs along a private right-of-way that does not disrupt traffic flow and runs through an area that can use a commuter train. But even so, if it wasn't for the Kenmore Square and Huntington Avenue subways, we probably would not have streetcars in Boston at all.

We may very well have had the Mattapan Line, though. The line runs along its own right-of-way where it does not disrupt car traffic, and the grade through which the Line passes is said to be too light to accommodate Red Line trains that could have passed through there, making PCCs, which are especially light cars, a great solution.

But in general, the only reason why we have streetcars in Boston today is because they serve their areas well without disrupting traffic flow. Either the street they run on is wide enough to accommodate their right-of way, they run in subways without having any impact on traffic flow or they serve a specific purpose for which they are needed. Subways practically require streetcars; while surface right-of-ways could have easily become busways, diesel and CNG buses like Boston uses emit fumes that make them too harmful to put them in a subway. Also, as the Silver Line' s South Boston Transit Way goes to show, even trackless trolleys are harder to maneuver in a narrow tunnel than a streetcar that will follow its preset track, making it easier to run streetcars along a tunnel.

By keeping the street-level right-of-ways served by streetcars, riders are provided with a quick one-seat-ride from the subway downtown rather than making them transfer to a bus. That, coupled with their specific right-of ways accommodation of traffic flow, makes running the B, C and E lines on the street and in the subway all the more practical. So in short, the streetcars we have were kept to this day because they served their areas well, particularly the tunnels that keep transit operations completely separate from traffic flow.

Next to go were street-running lines that fed into tunnels. By 1958, all of the Cambridge lines had been eliminated and replaced with more-maneuverable trackless trolleys. The Lenox Street Line was the next to go in 1961; it ran along Tremont Street in street-running form before feeding into the Pleasant Street Portal and entering the subway. Finally, lines such as the Watertown and Arborway Lines, which were only street-running for part of their ways, were eliminated. After 1985, the only street-running line that would last was the E Line to Heath Street, and that was only because it served a significant purpose—shuttling patients to and from the VA Hospital.

Today, we are left with five lines. If they had not run along their own right-of-ways, they would undoubtedly been gone too. There is no way that the B and C would have lasted until today if they still ran through Kenmore Square on street-running tracks. The C Line in particular would have been eliminated in the early 1960s, when the Mass Pike was constructed and the Beacon Street Overpass was constructed to carry traffic across the new highway. The bus that would have "temporarily" replaced the streetcar would have seemed like the simpler long-term transit solution for the corridor. Likewise, the E Line would have been quickly eliminated if it still ran through busy Copley Square on street-running tracks. The Boylston Street Portal through which the line once ran might very well have been sealed and paved over to widen Boylston Street.

That leaves the D and Mattapan Lines. The D Line might never have been constructed in 1959 if the subway under Kenmore Square did not exist for it to feed into and run through to downtown Boston. At most, the D Line would have run to Fenway Station and cut back there, which would have worked well as the line runs along a private right-of-way that does not disrupt traffic flow and runs through an area that can use a commuter train. But even so, if it wasn't for the Kenmore Square and Huntington Avenue subways, we probably would not have streetcars in Boston at all.

We may very well have had the Mattapan Line, though. The line runs along its own right-of-way where it does not disrupt car traffic, and the grade through which the Line passes is said to be too light to accommodate Red Line trains that could have passed through there, making PCCs, which are especially light cars, a great solution.

But in general, the only reason why we have streetcars in Boston today is because they serve their areas well without disrupting traffic flow. Either the street they run on is wide enough to accommodate their right-of way, they run in subways without having any impact on traffic flow or they serve a specific purpose for which they are needed. Subways practically require streetcars; while surface right-of-ways could have easily become busways, diesel and CNG buses like Boston uses emit fumes that make them too harmful to put them in a subway. Also, as the Silver Line' s South Boston Transit Way goes to show, even trackless trolleys are harder to maneuver in a narrow tunnel than a streetcar that will follow its preset track, making it easier to run streetcars along a tunnel.

By keeping the street-level right-of-ways served by streetcars, riders are provided with a quick one-seat-ride from the subway downtown rather than making them transfer to a bus. That, coupled with their specific right-of ways accommodation of traffic flow, makes running the B, C and E lines on the street and in the subway all the more practical. So in short, the streetcars we have were kept to this day because they served their areas well, particularly the tunnels that keep transit operations completely separate from traffic flow.