Trolley Types of Boston

1955 shot of a Type 5 streetcar on the 29/Mattapan-Egleston line in Mattapan Square entering the Mattapan terminal. Type 5s served Boston's streetcar operations for over thirty years, a testament to their notable reliability. Image copyright Frank Pfuhler.

From the start of electric trolley service in Boston in 1887, a variety of trolley types have come and gone. From streetcars to trackless trolleys to the modern light rail vehicle (LRV), a waiting Boston transit rider could have been picked up by a diverse roster of trolleys over the years! And as a testament to the reliability of electric vehicles, many trolleys of varying ages have operated, and continue to operate, simultaneously—in the late 1940s, BERy used seven different models of trolleys! While this number has fallen over the years, it remains high today; as of 2013, five different models of trolleys remain in revenue operation across the MBTA's system. This article is dedicated to examining the evolution of Boston's trolley cars over time-what cars have been used over the years, how cars have changed over the years and what needs prompted the addition of additional features to the cars.

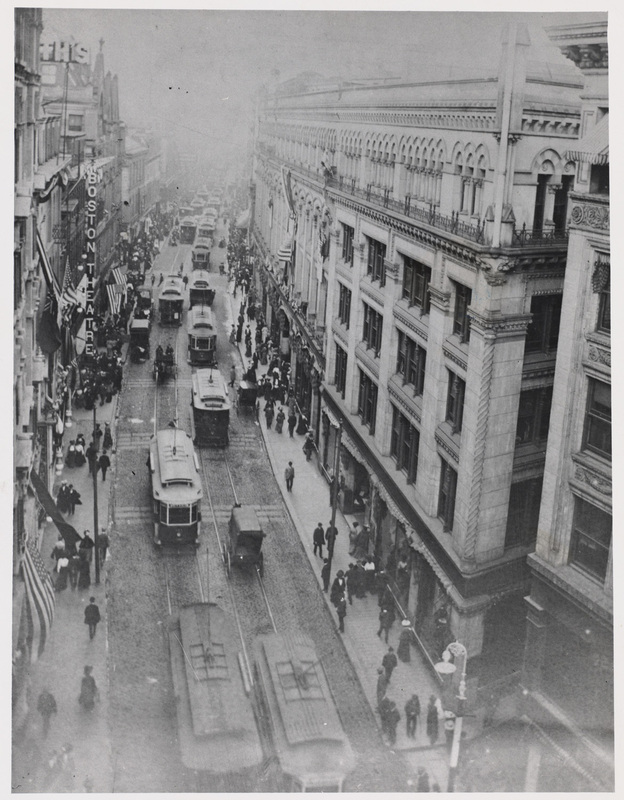

Converted Horsecars

Several converted horsecars running along Washington Street as electric streetcars around the turn of the century.

The first streetcars to hit the streets of Boston were the same horsecars that had served the city previously, only with electric trolley poles on top. Much of the horsecar inventory around 1890, when the first electric streetcar lines began operating in Boston, was still robust and had years of usable life remaining; therefore, the West End Street Railway, the precursor of BERy, simply took its existing horsecars and outfitted them with equipment to draw power from electric overhead wires. Suspension, wheels and brakes also had to be replaced with stronger, heavier equipment to better handle the streetcars' new electric motors and additional equipment. The streetcars also gained lighting and heating systems, making night service much more practical as passengers could see and would stay warm during Boston's often freezing cold winter nights!

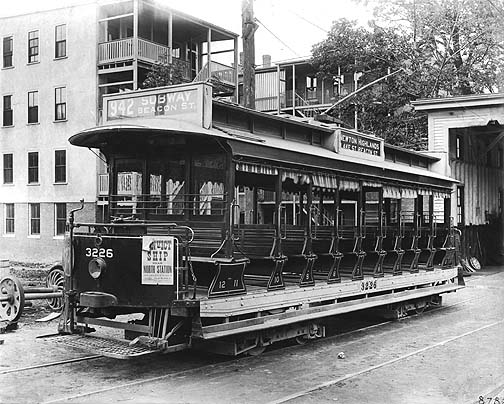

Some dedicated streetcars were purchased during the early 1890s, though the majority of Boston's streetcars remained converted horsecars well into the early 1900s (by 1907, Boston had much more modern Type 1, 2 and 3 cars running along its streets, marking the end of the horsecar era). A converted horsecar could be told apart from a dedicated electric streetcar because the horsecars retained their horse-harnessing mechanism, which was retained in case the cars would need to be used in the future with horses once more:

Some dedicated streetcars were purchased during the early 1890s, though the majority of Boston's streetcars remained converted horsecars well into the early 1900s (by 1907, Boston had much more modern Type 1, 2 and 3 cars running along its streets, marking the end of the horsecar era). A converted horsecar could be told apart from a dedicated electric streetcar because the horsecars retained their horse-harnessing mechanism, which was retained in case the cars would need to be used in the future with horses once more:

Converted horsecar at the old Reservoir Carhouse in Brookline around the turn of the century. The car still retains the harnessing mechanism at the front that would have been used to connect a horse to it. To see how the horse was connected to the horsecar, see the photograph below:

Hoersecar in Dorchester, most likely in the 1880s-1890s. Look at how the horses were attached to the horsecar, then look at the previous photograph again and you will see that the converted horsecars retained their horse-harnessing mechanism. Also note that the converted horsecars have stronger wheels and have gained electric equipment such as front headlights.

Dedicated streetcar in Coolidge Corner in Brookline around the turn of the century. As you can see, there is no horse-hitching equipment at the front of the car, and there is an enclosed vestibule at the front for passengers to board and the operator to sit. Over the years, the converted horsecars began to receive enclosed vestibules as well to shield the operator and riders from the elements. Now that streetcars could be electrically heated, it was best to insulate the streetcar as well as possible. Image courtesy Brookline Historical Society.

One could still find converted horsecars operating in Boston in the mid-1910s; by the 1920s, Type 4 and 5 cars had arrived and the only converted horsecars remaining in the BERy system were work cars. (Note: for a most interesting 1910s adaptation of the converted horsecar (and in some cases dedicated 1890s streetcars as well), the "snake-car," see the following page: http://www.virtualrailroader.com/CEBoston2B.html

Types One, Two and Three

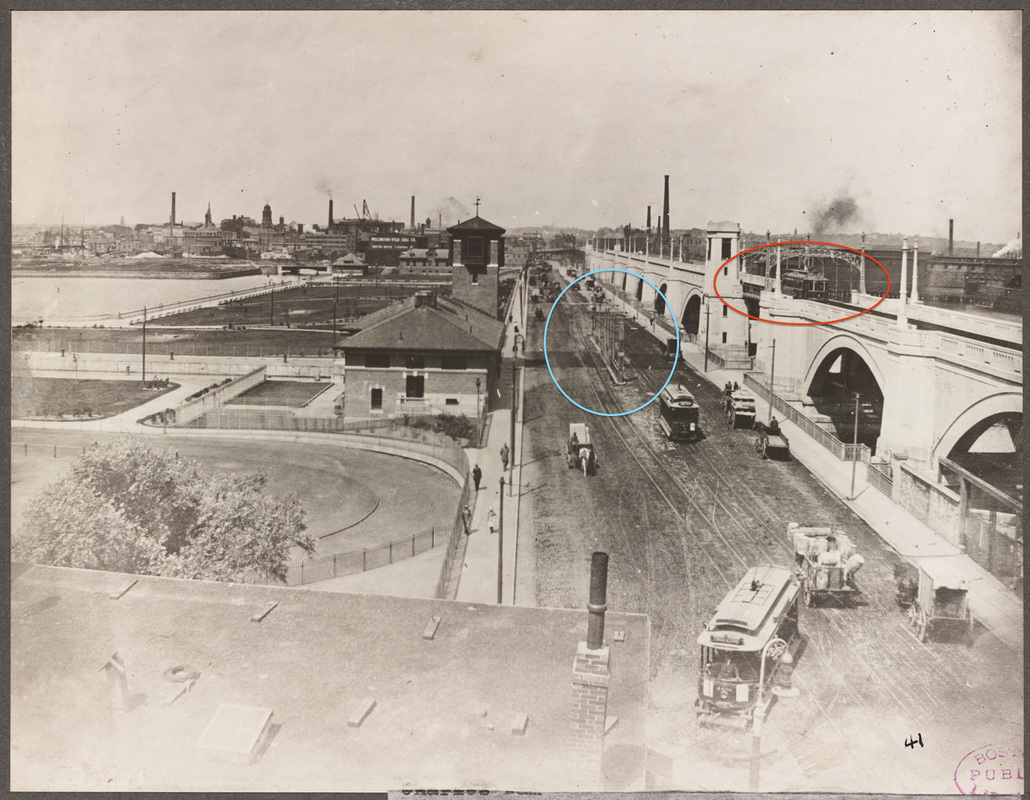

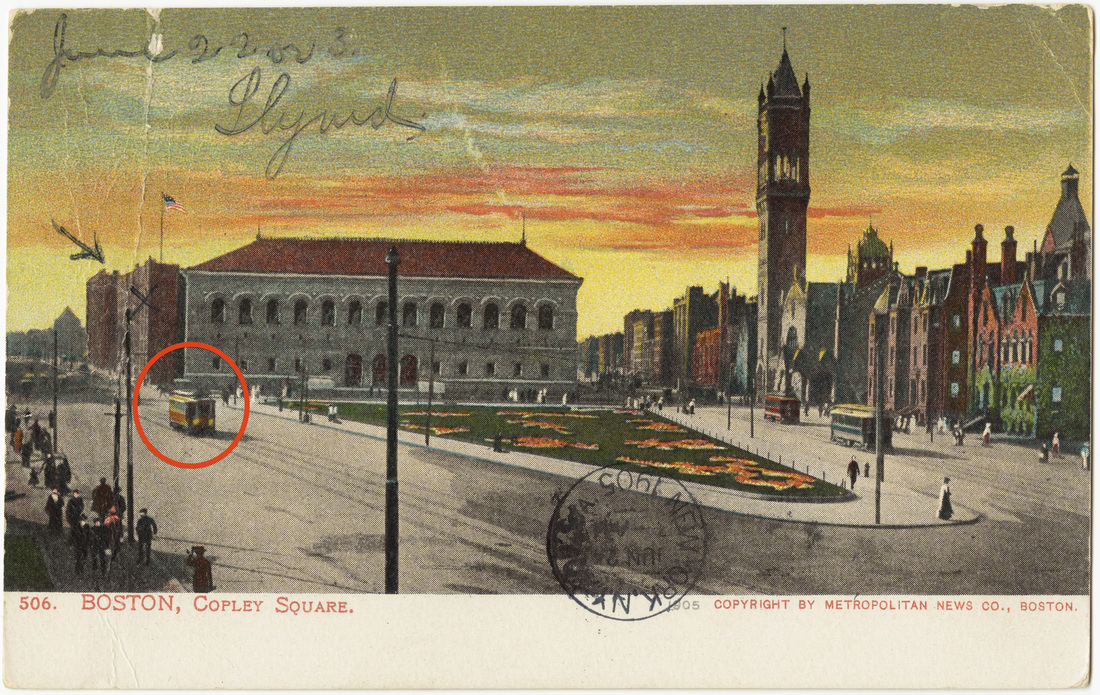

Lechmere Viaduct in the mid-1910s. Circled in red is a Type One, Two or Three streetcar—the cars all looked exactly the same and were numbered based upon their introduction to the BERy system.

By the mid-1900s, converted horsecars, which had been serving Boston since long before their conversion to streetcars in the late 1880s-early 1890s, were beginning to show their age, necessitating the Boston Elevated Railway's procurement of new, more modern streetcars. Those cars were the Type One, Type Two and Type Three streetcars. All three of these streetcar types were acquired within one year from one another (Type Ones in 1905 (numbered 5001-5040), Type Twos in 1906 (numbered 5041-5090), Type Threes in 1907 (5091-5190)) and were remarkably similar to one another mechanically and physically. The only difference was that Types One and Two were built by Brill, and Type Threes are built by the St. Louis Car Company.

Unlike earlier converted horsecars, the new streetcars were closed and did not have open windows, making the cars much better suited for frigid New England winters. The cars were also the first to have folding doors, controlled by air pressure release (more on how streetcars work in "How A Streetcar Works").

Unlike earlier converted horsecars, the new streetcars were closed and did not have open windows, making the cars much better suited for frigid New England winters. The cars were also the first to have folding doors, controlled by air pressure release (more on how streetcars work in "How A Streetcar Works").

Type One, Two and Three cars remained in service for over twenty years—all three were retired around 1930. Many Type Ones, Twos and Threes saw continued lives as work cars throughout the BERy system—snowplows, compressor cars, etc.

Since the postcard of Copley Square above is dated 1905, it can be assumed that the covered streetcar circled in red is a Type one, as that is the only one of the three that would have been in service then. The other two streetcars on the right appear to be converted horsecars.

Type Two #5060 in service in an unidentified location.

Same Type Two #5060 at the Seashore Trolley Museum today, beautifully restored to its original BERy pre-cream and orange green, white and red paint scheme. Image copyright Seashore Trolley Museum.

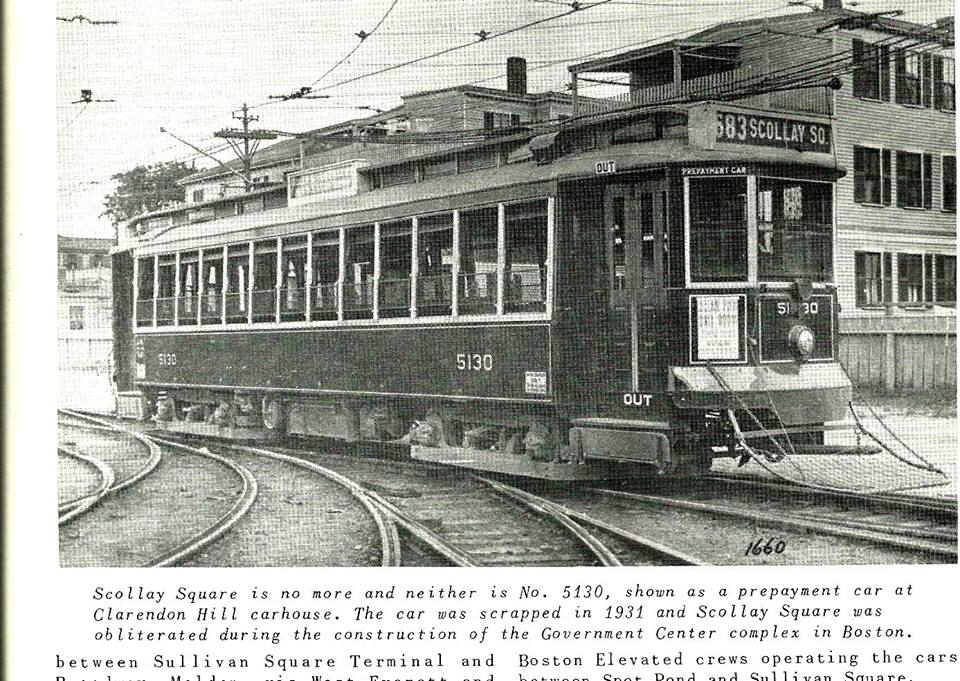

Type Three #5130 pictured at Clarendon Hill Carhouse in Somerville. Compare the car to the Type One and Two pictured above, and you will see that the three streetcars had almost exactly the same chassis.

Type Three making its way down the Columbia Road streetcar reservation in 1940 as a converted snowplow immediately following that year's Valentine's Day Blizzard. Many Type One, Two and Three streetcars, as well as converted horsecars earlier on, later saw continued usage as snowplows, compressor cars and other work cars following their retrial around 1930. Image courtesy Boston City Archives.

Note: The last active Type Three streetcar in the Boston system was #5164, a snowplow that served the system until 2006, at which time it was used on the Mattapan Line. The car is currently housed at the Seashore Trolley Museum after serving Boston for 99 years! The car is pictured below:

#5164 in Mattapan Yard in the 2000s. Image copyright Dorchester Reporter.

Center-Entrance

Center-entrance cars were the Type Eight streetcars of the first half of the twentieth century. Known for high capacity, center-entrance cars were extremely reliable (arguably weakening their comparison to Type Eights) and were frequently used during peak hours of service on BERy (and later MTA) streetcar lines. Center-entrance cars were even somewhat accessible; with center stairs that were less than ten inches high and a very wide doorway, they were much easier to board than the typical Type Four or Five, making center-entrance cars extremely useful with large crowds. Accordingly, Type Eights were designed to have low floors so as to ensure that every train on the Green Line will be accessible.

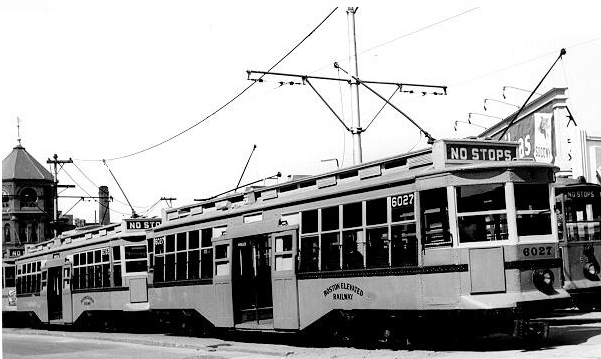

Center-entrance train on the old Huntington Avenue streetcar median; at left is the old Mechanics Building (see "E Branch" and "Copley Square" for more information). Judging by the additional streetcars on the westbound side of the median and the "No Stops" sign on all of the cars, these cars are all being stored for a special occasion, such as the annual Schoolboys Parade; the Huntington Avenue median, as it was separate from traffic, was frequently used to store cars when extra space was necessary. As you can see, the cars' center-entrance was very wide, and the step to get onto the cars was very low, allowing for very easy pedestrian access. Image copyright Bill Volkmer.

Center-entrance cars waiting for a game to end at Braves Field, the former home of the Boston Braves (see "B Branch" for more information), a frequent destination for center-entrance cars which, with their large capacity, could quickly swallow the large gametime crowd. This view provides an additional look and the significantly low step to enter the cars. Image copyright Joe Testagrose.

There were two types of center-entrance cars: self-propelled and trailers. Self-propelled center-entrance cars were your typical double-ended streetcar that could be driven from either end. Trailers were, as their name indicates, streetcars that could only be operated when another streetcar up ahead was pulling them forward. Center-entrance trailers were used almost exclusively with Type Four streetcars (see below) pulling them (note: the second photo in the Type Four piece shows this combination beautifully).

Single self-propelled center-entrance car in Watertown Square. Like any other self-propelled streetcar, the car above has trolley poles above and a light up front. Image copyright Bill Volkmer.

Center-entrance trailer in Boston. Note the streetcar on the left, a Type Four that will pull the trailer. Note that the Type Four is signed Braves Field. Also note that the car has couplers like the self-propelled center-entrance car above, yet it lacks trolley poles, as it cannot propel itself, and a light, as it will always be the rear car and will never have an operator who will need to see ahead. Image copyright Bill Volkmer

By the late 1930s, center-entrance cars, which had entered service in 1915, were nearing the end of their lifespan and were beginning to be scrapped. Luckily, BERy kept most of the cars in storage at Everett Carhouse and other storage facilities; in due course, the cars became necessary to continue service on BERy streetcar lines. With the breakout of World War Two in 1942, the BERy system was forced to operate at peak capacity (see "Type Fours," the next piece in this article, for more on World War Two). As you can imagine, center-entrance cars' high capacity came in extremely handy when trying to handle the significantly increased ridership.

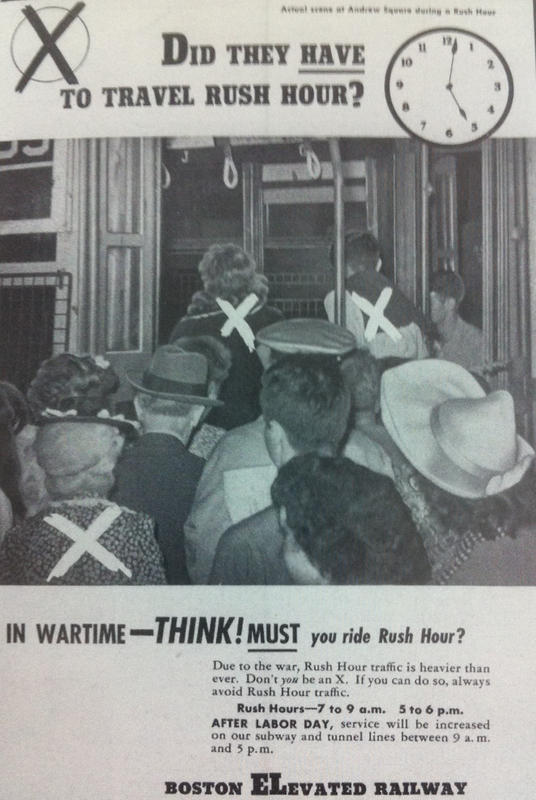

BERy ad run during Wartime telling riders to ride streetcars less if they can because ridership is becoming too hard to handle!

Center-entrance cars saw service on the BERy system until 1953 on a much-extended service span stemming from wartime ridership and a subsequent need for good, reliable streetcars following the war, when most Type Fours were ready for the scrap yard and PCCs were just beginning to arrive in Boston.

Type Four

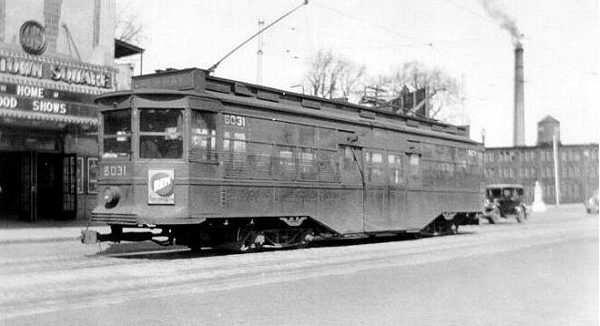

Type Four streetcar in Mattapan Square on the Blue Hill Avenue center reservation, most likely in the early 1920s.

Type Four cars, first delivered to the Boston Elevated Railway in 1911, were a mainstay of the BERy (and later MTA) fleet until their retirement in 1950, serving Boston for almost forty years. The BERy fleet included 285 Type Fours, which ran all around Boston on streetcar lines from Mattapan to East Boston and everywhere in between. Type Fours notably ran in combinations with center-entrance trailers, much like Type Seven streetcars run in combinations with Type 8 streetcars on the Green Line today.

Type Four pulling a center-entrance trailer along a snowy Mattapan High-Speed Line. Nowadays, the Type Eight streetcars, while they can propel themselves, serve a similar purpose, as they are as a default run in trains with Type Seven streetcars so as to increase the train's passenger capacity and ensure that there is at least one car accessible to people with disabilities per train. Image courtesy Railroad.net User 3rdrail.

Type Seven (left) and Type Eight (right) combination on the Green Line today. Photo taken on Huntington Avenue (E Branch) right by Forsyth Way from an office at Northeastern University. Image copyright Me (Gil Propp).

By the early 1940s, after thirty years of service without significant restoration work, Type Four streetcars were beginning to fall apart. Type Fours would most likely have been scrapped at this time, as Center-Entrance cars were beginning to be, if it were not for the United States' entry into World War Two. Now, with soldiers off at war and the taxis and cars they would have driven taken for metal to support the war effort, BERy was faced with higher ridership that it had experienced in years. Suddenly, it was necessary to pull any equipment that could possibly be procured into revenue service immediately. Center-Entrance cars were pulled off the scrap lot, and throughout the war years BERy operated to the limits of its capacity.

By the end of the War, BERy's streetcar infrastructure was in terrible shape. Not only had there been high ridership, but those workers who would have maintained the streetcars and the track infrastructure had been off at war, resulting in significant deterioration. At this point, BERy chose to convert many streetcar lines to buses rather than invest in necessary repairs. Those lines that remained in service were served by cars that were in dire need of repairs or replacements.

By the end of the War, BERy's streetcar infrastructure was in terrible shape. Not only had there been high ridership, but those workers who would have maintained the streetcars and the track infrastructure had been off at war, resulting in significant deterioration. At this point, BERy chose to convert many streetcar lines to buses rather than invest in necessary repairs. Those lines that remained in service were served by cars that were in dire need of repairs or replacements.

1940s photograph of a beat-up Type Four streetcar alongside a shiny new diesel bus, both operating in East Boston most likely.

Starting after the War in 1944, many Type Four and Type Five (see below) cars were replaced by PCC streetcars (see below); by 1951, there were 321 PCCs in service in Boston, up from 21 prior to the War! The Type Four and Type Five streetcars that remained in service only continued to fall apart. The major issue with Type Four cars in particular was not their rusty exterior or chipped interior—Type Fours were especially notable for brake failures. The War took an especial toll upon these aged cars; as a result of their heavy usage at their age, many Type Fours had slack brakes following the War. Two significant accidents occurred with Type Four streetcars during the late 1940s—firstly, the Egleston Square Tragedy in 1948, in which the operator of a Type Four on the 29/Mattapan-Egleston line lost control of the car's braking system, causing it to crash into Egleston Station at the end of the line and resulting in loss of lives and significant injuries and property damage.

Type Four streetcar crashed into Egleston Station in 1948. Following the crash, Type Four streetcars were immediately removed from the 29/Mattapan-Egleston line, which from then on was served by Type Five streetcars until its bustitution in 1955. Image courtesy Boston Public Library.

Next was a strange accident that occurred in 1950, which was the last straw for Type Fours in Boston. A Type Four that had been parked at Heath Street Loop on Mission Hill in Roxbury, about to serve the 57/Heath Street Loop-Subway line (predecessor to the modern abbreviated E Line), suddenly slid out of the loop, down South Huntington Avenue and onto Huntington Avenue, derailing soon afterwards. Damage was minimal as nobody had been on board the streetcar at the time of the brakes' release; it is believed that the accident may have been caused by a child reaching into the streetcar and releasing the brakes. Even so, given past brake failures on Type Fours, Type Fours were fully dismissed from service soon afterwards.

Type Four accident on Huntington Avenue in Mission Hill/Roxbury in 1950. Luckily, there were no passengers or streetcar operators on board when the streetcar was let loose, and only a telephone pole sustained damage upon the Type Four's derailment!

Type Fours were removed from the MTA's operating roster in 1950, after thirty-nine years of service. To date, they served Boston's streetcar operations for longer than any non-PCC streetcar to ever run in the city.

Type Five

Type Five car # 5738 on Blue Hill Avenue in Dorchester by the Mattapan line, operating north on the 29/Mattapan-Egleston line, by the intersection of Blue Hill Avenue and Ansel Road, just north of Morton Street, on May 29th, 1955, a little over three months before the 29 line's bustitution.

Image copyright Frank Pfuhler.

Image copyright Frank Pfuhler.

Type Five streetcars were known for their reliability and durability; accordingly, they served Boston's streetcar operations for thirty-six years. Some Type Fours lasted for fourteen additional years after the end of the War, until 1959! Only three years shy of the Type Fours, and longer than any other non-PCC streetcar, other than the Type Fours, that ever ran in Boston to date. The fact that the Type Fives entered service twelve years after the Type Fours made a big difference as to their readiness to serve the heavily-increased wartime ridership; accordingly, while no Type Fours remain in any shape or form today, five Type Fives survive today in Trolley Museums across the East Coast.

Type Five #5645, featured in Streetcar Tracks, at the Connecticut Trolley Muesum. Image copyright Me (Gil Propp).

If you have ridden a Type Five at a trolley museum, as I have at the Connecticut Trolley Museum while filming Streetcar Tracks, you may have noticed that the streetcar was significantly noisier than any modern streetcar. This is because of the Type Five's antiquated air compressor, which converts electricity from overhead wires into energy to propel the streetcar. When Type Fives would run through the Subway, they would make a very loud racket, as all of the noise would reverberate off of the sides of the tunnels.

YouTube clip of Type Five #5645, featured in Streetcar Tracks, operating at the Connecticut Trolley Museum. Listen closely, and you will hear the characteristic whine of the streetcar's air compressor. Imagine a noise that loud and high reverberating off of the tunnels of the subway! Particularly at a time when streetcars' windows could be opened and closed by riders, the noise would have been deafening!

Nowadays, air compressors are much quieter; ride a PCC on the Mattapan High-Speed Line, and you will see that already in 1945, streetcars were built with much more modern technology that made much less noise. Accordingly, once enough PCCs were acquired to provide service on subway lines, Type Fives were restricted solely to surface lines for the remainder of their usable lives, leaving the subway to be served by modern, quiet PCCs.

Pullman & Brill Trackless Trolleys

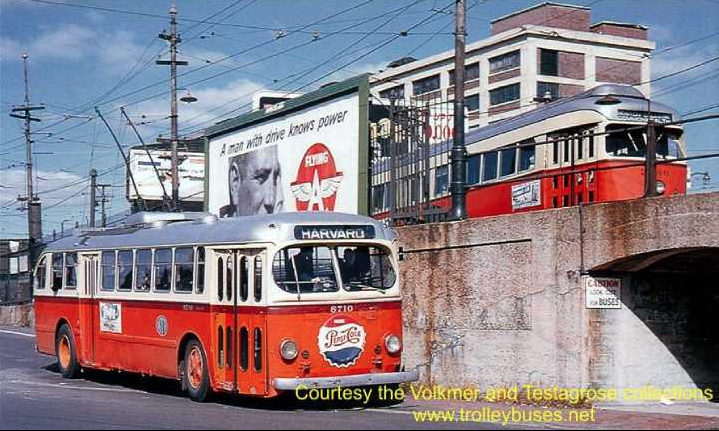

Pullman trackless trolley exiting the Harvard Bus (formerly streetcar) Tunnel onto Mount Auburn Street/Eliot Square in 1967, nine years after the last streetcars stopped in Harvard Square. The trackless is running on the 71/Watertown-Harvard line, which was served by streetcars until 1958—along with the 73/Waverley-Harvard line, the 71 was the last streetcar line to serve Harvard Square; both are still served by trackless trolleys today.. Note the streetcar tracks still embedded in the pavement. A mall sits over this location today, with buses and trackless tolleys passing under it to enter the tunnel.

Image copyright Bob Coolidge.

Image copyright Bob Coolidge.

Note: to learn more about the history of trackless trolleys in Boston, visit "Trackless Trolleys"

As the car grew in popularity, streetcars, which are bound to tracks and cannot switch lanes or pull to the side of the road to stop, began to be seen as antiquated nuisances in need of modernization. Before diesel buses, which have limited ranges in comparison to trolleys, which have an unlimited supply of power from overhead wires, were refined enough to serve trunk (high-traffic, long-distance) routes through Boston, BERy (and later the MTA) brought in trackless trolleys to ease traffic flow on busy Boston streets, which were beginning to grow congested with car traffic.

Newton Corner back in 1961, when it boasted a streetcar (the A Line, then the 69/Watertown-Subway streetcar). As you can see, the streetcar ran in the center of the street, in the left lane, along with traffic. When the streetcar stopped, all cars in both lanes would have to stop so that passengers could disembark As you can imagine, many Bostonians were annoyed that they had to stop so ofter since the streetcar could not pull to the side of the road, a feeling that ultimately led to the demise of streetcars in Boston.

Trackless trolleys were seen to be, and in some cases were, better-suited to serve Boston's streetcar lines mainly because of their side-to-side maneuverability. Because they had rubber tires and were not confined to tracks, trackless trolleys could switch between lanes on a street and pull to the side of the road to let passengers disembark, easing traffic flow. Add to that trackless trolleys being quieter than many of the streetcars that ran in Boston at the time, as well as their being more narrow, and therefore more easily maneuverable and less space-hogging, than streetcars (also a disadvantage as that meant that the trackless trolley could carry less people than a streetcar), and it is clear why trackless trolley gained approval in Boston upon their introduction in the late 1930s.

The first trackless trolley conversion in Boston occurred in 1936, when the 77/Harvard-Lechmere streetcar, now the 69/Harvard-Lechmere bus, was converted from streetcars to trackless trolleys. Performing the conversion was relatively easy; all that had to be done was add a second overhead wire to electrically ground the trolley as it was no longer grounded through its metal wheels (more on how a trackless trolley works in "How A Streetcar Works").

Late 1930s BERy trackless trolley, made by Pullman and signed for Lechmere. Note the double trolley poles above and the rubber tires belo.

One of four 1937 Twin Coach trackless trolleys acquired by BERy operating on Route 72 (Huron Avenue) near Fresh Pond in Cambridge.

The first trackless trolleys to enter service in Boston were built by Pullman. Between 1936 and 1950, BERy (and later the MTA) acquired 610 trackless trolleys, virtually all built by Pullman (except for four acquired from Twin Coach in 1937), of varying body styles as more and more lines were converted and demand for trackless trolleys increased. There were two basic body styles—the older one pictured above and the later one pictured below. Some trolleys had left hand doors (those used in the Harvard Streetcar (now Bus) Tunnel), and others did not. Later trolleys tended to be longer and had a higher passenger capacity.

Pullman trackless trolleys in Harvard Square in the 1940s.

In 1950, the MTA acquired 25 trackless trolleys from ACF/Brill. These would be the last trackless trolleys the MTA would acquire until 1976—ten years later, almost every trackless trolley route in Boston would be bustituted, and many of Boston's trackless trolleys would be scrapped.

Brill trackless as viewed from the rear. Note that the back is shaped slightly differently from the Pullman trackless pictured in the last photo.

Brill trackless as viewed from the front. Compare to the Pullman trackless pictured two photos ago, and you will see that, other than a slightly more rounded windshield on the Brill, the two tracklesses looked remarkably similar. The Brill pictured here is just by Lechmere Station, most likely on the 69/Harvard-Lechmere line (first trackless conversion in Boston) given its roll sign—note the PCC about to cross the Lechmere Viaduct on its way to Commonwealth Avenue in Brighton as indicated by its roll sign.

Note: for a great chart showing the dates at which different batches of trackless trolleys arrived in Boston and their numbering scheme, visit http://www.trolleybuses.net/bos/bos.htm

PCC

"All-Electric" PCC #3219, with characteristic picture windows along its roofline, turning south onto Washington Street in Jamaica Plain under the Washington Street Elevated towards Arborway Station out of Arborway Yard. At left are the oil tanks formerly owned by Boston Consolidated Oil Company; further left is the railroad right-of-way formerly occupied by a NY NH & H RR embankment and today occupied by the Southwest Corridor.

(Thanks Samuel Martland for helping identify the location!)

(Thanks Samuel Martland for helping identify the location!)

By the early 1930s, Boston's streetcars were beginning to appear and feel antiquated in comparison to sleek new buses and trackless trolleys. Around the United States, many cities were beginning to or had already replaced most, if not all, of their streetcar lines with buses or trackless trolleys; even Boston had already swapped some. Yet practically speaking, it did not make sense to completely do away with streetcars right away; the tracks and wires were there, the vehicles just had to be modernized. Therefore, representatives of leading transit agencies from cities around the United States gathered in the early 1930s to design together a new standard streetcar that would successfully transition streetcar lines into modern times.

The result was the PCC streetcar, a sleek, quiet, modern-looking new streetcar that was quickly adopted by a variety of transit associations and were built by the St. Louis Car Company and Pullman-Standard. The first PCCs went to Brooklyn, NY in 1935; shortly afterwards, in 1937, Boston took delivery of its very first PCC. Built by the St. Louis Car Company, later to prove to be the only non-Pullman Boston PCC, PCC #3001, dubbed the "Queen Mary," lacked a left-hand door and as a result rarely ran in the Subway and only saw service on surface street-running lines without center platforms of configurations that would require a left-hand door.

The result was the PCC streetcar, a sleek, quiet, modern-looking new streetcar that was quickly adopted by a variety of transit associations and were built by the St. Louis Car Company and Pullman-Standard. The first PCCs went to Brooklyn, NY in 1935; shortly afterwards, in 1937, Boston took delivery of its very first PCC. Built by the St. Louis Car Company, later to prove to be the only non-Pullman Boston PCC, PCC #3001, dubbed the "Queen Mary," lacked a left-hand door and as a result rarely ran in the Subway and only saw service on surface street-running lines without center platforms of configurations that would require a left-hand door.

Boston PCC #3001, the "Queen Mary." Note the car's lack of a left hand door, as well as Tomlinson Couplers—upon its arrival in Boston and for years thereafter, #3001 was truly one-of-a-kind and could not couple with any other car. All later Boston PCCs were equipped with Tomlinson Couplers.

Given the roll sign, the track and wire infrastructure and the house in the background, the car is most likely pictured in Arborway Yard in Jamaica Plain, though it is also possible that the car is pictured at Charles River Loop in West Roxbury.

Given the roll sign, the track and wire infrastructure and the house in the background, the car is most likely pictured in Arborway Yard in Jamaica Plain, though it is also possible that the car is pictured at Charles River Loop in West Roxbury.

After the delivery of the "Queen Mary," no more PCCs were delivered to Boston until 1941, when PCCs #3002-3021 were delivered. These PCCs came to be known as "Pre-War" PCCs, as in 1941, the United States joined World War Two, significantly delaying PCC deliveries as no workers were at hand to build the cars.

PCC #3003, a "Pre-War" PCC, operating in Boston. Judging by the architecture in the background and the roll sign displaying "Subway," this picture was most likely taken on Tremont Street in the South End along the 43/Subway-Egleston via Tremont Street streetcar line. Route 43 was served by streetcars until 1961, albeit cut back from Egleston Square in Roxbury to Lenox Street Loop in the South End, and was the last non-MBTA streetcar line in Boston and the last line to enter the Subway via the Pleasant Street Portal. "Pre-War" PCCs were a common sight on Route 43, and accordingly these PCCs won the nickname "Tremont" PCCs as they quickly became synonymous with Tremont Street in the South End. Image courtesy Connecticut Trolley Museum

Boston desperately needed new streetcars, as even before the War the existing fleet was beginning to show its age. All the more so after the war, as explained earlier on this page.. Accordingly, following the War, a plethora of "Post-War" PCCs began to be delivered to the city.

Brand-new "All-Electric" PCC #3210 being delivered to Boston via the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad (NY NH & H RR)'s Providence Division, the predecessor to the Southwest Corridor (see "Copley Square" for more information on the NY NH & H RR).

Image courtesy Walker Transportation Collection.

Image courtesy Walker Transportation Collection.

By 1946, there were 250 "Post-War" PCCs, numbered 3022-3271, operating in Boston, allowing BERy (and starting in 1949 the MTA) to begin retiring older streetcars, many of which had long surpassed their practically usable life.

Two "Post-War" PCCs running in a train through Packard's Corner on the 62/B streetcar line along Commonwealth Avenue in Allston, near Braves Field and Boston University. The PCC at the head of the train in passing over the switch used for 69/A streetcars to continue onto the Commonwealth Avenue streetcar median and to the Subway from Brighton Avenue, the street up ahead on the right.

25 of the "Post-War" PCCs running in Boston by 1946, 3197-3221 to be exact, were different from the rest in that they were built according to the new "All-Electric" standard. Unlike the rest of Boston's "Air-Electric" PCCs, which used air pressure for braking and opening and closing doors and required the operator to manually crank the trolley's roll sign, "All-Electric" PCCs handled all of these functions electrically. "All-Electric" PCCs are distinguishable from the rest by their "picture-windows" along their roofline.

"All-Electric" streetcar #3220, one of the 25 original "All-Electric" PCCs delivered to Boston, on Route 71 along Mount Auburn Street in Watertown about to enter Watertown Square. The photograph above was taken on September 3rd, 1957; a year later, this line will be converted to trackless trolleys. Route 71 remains a trackless trolley route to this day, one of four remaining trackless trolley routes in Boston.

Since the "All-Electric" PCCs' functions were controlled electrically, they were not mechanically compatible with the MTA's "Air-Electric" PCCs, meaning they could not be towed by one another in trains. Originally, the "All-Electric" PCCs could only run as single cars, but around 1960 couplers were added to them, allowing them to run in trains with one another (though still not with "Air-Electric" PCCs).

"All-Electric" #3221 with a coupler at its front, allowing it to couple with other "All-Electrics" (though not with "Air-Electrics").

Since the MTA had a primarily "Air-Electric" fleet, it was impractical to continue acquiring "All-Electric" PCCs that would not be compatible with the rest of the fleet. Therefore, when the MTA purchased fifty more PCCs in 1951, numbered 3272-3321, those PCCs were styled in the more up-to-date styling of the earlier "All-Electrics" with picture windows along their rooflines, yet they were built to "Air-Electric" mechanical specifications so as to make them mechanically compatible with the rest of the MTA's fleet. Hence, the new PCCs earned the name "Picture-Window" PCCs. After the delivery of the "Picture-Window" PCCs to the MTA in 1951, the total number of PCCs in Boston was 321., allowing the MTA to completely retire its decrepit Type Fours, which had been pulled out of service in 1950.

"Picture-Window" PCC pulling a "Post-War" PCC through Cleveland Circle in Brookline along the present-day C Branch of the Green Line.

PCC #3314, a "Picture-Window" PCC delivered in 1951, pulling another "Picture-Window" in the 1980s along the E-Arborway Line; the similarly-styled "All-Electric" PCCs had already been scrapped in the mid-1970s. Note the green coat of paint—when the MBTA assigned colors to its transit lines in 1967 and the remaining streetcar lines (that ran through the Subway) became the Green Line, virtually every Boston PCC was repainted green. Also note the line of cars behind the train—the Arborway Line ran with traffic along single-lane streets, requiring cars to stop every time the streetcars stopped at stations—a key factor in the line's subsequent bustitution (see "What Happened to the Arborway Line?" for more on the Arborway Line).

By the mid-1950s, the MTA was once again in need of new streetcars with the remaining Type Fives reaching the end of their usable lives. Looking to save money, the MTA turned to the used streetcar market and gained word that Dallas, Texas was ending streetcar service. Accordingly, in 1958, the MTA purchased 25 retired PCCs, numbered 3322-3346, from Dallas, resulting in the complete end of Type Five service in 1959.

Dallas PCCs painted green stopped at Mattapan Station in the 1970s. While the Mattapan Line is considered part of the of the Red Line (likely the reason for the red poles in the station), these Dallas PCCs served on the Green Line beforehand and accordingly were painted green. Dallas PCCs were originally painted in MTA Orange, and they will soon be painted red for the remainder of their time on the Mattapan Line. Image copyright Joe Testagrose.

The Dallas PCCs were significantly different from the rest of Boston's PCCs in that they were double-ended. Previously, Boston had only ordered its PCCs single-ended as the remaining streetcar infrastructure by the 1940s was almost completely equipped with loops. The Dallas PCCs double-ended capability would come in handy later on, particularly now that the Type Fives, the last remaining double-ended cars in Boston, were retired, as many of Boston's streetcar lines, particularly the E Branch, have cutback switches along the way that can be used by early-truncating runs on the line.

Dallas PCC entering the Huntington Avenue Subway; picture taken from eastern end of Northeastern University/Opera Place Station. As you can see, the back of the double-ended Dallas PCC is capable of propelling the PCC as well as the front; an operator could stop the trolley, switch the poles, move to the back and begin to move the trolley back towards Northeastern. Note the "Northeastern University" rollsign on the Dallas PCC; the car was likely operated from what is now the back end from the subway to Northeastern, then switched ends by the operator at the station's track switch to be operated back into the subway from the opposite end. Image copyright Frank Florianz.

PCCs continued to run on the MBTA's Green Line until 1985. By 1978, all of the Dallas PCCs had been retired, and by the 1980s, PCCs were confined almost exclusively to the E Branch of the Green Line, as the new Boeing LRVs could not handle the curves and street-running tracks of the E Branch past Brigham Circle without high risk of derailing due to their articulation.

As can be expected after years of soldiering on and reliably serving a transit agency, the MBTA's PCCs were beginning to show their age by the 1970s. In addition to shabby paint, some sported significant rust on their bodies and were not entirely mechanically sound and, to say the least, were in dire need of restoration.

Green Line PCCs on the A/Watertown Line in 1972, three years after the end of service on the Line, on one of many non-revenue moves to Watertown Carhouse over the years following the Line's suspension from service (see "What Happened to the A Line?" for more information). These particular PCCs have been freshly painted with in new green paint following the MBTA's assumption of the MTA's network in 1964 and the assignment of colors to the MBTA's lines in 1967, yet even a new coat of paint cannot completely hide the rust the is beginning to show on these "Post-War" PCCs following almost thirty years of service.

Starting in the late 1970s through the early 1980s, the MBTA embarked upon an ambitious PCC overhaul campaign to usher its remaining PCCs into the 1980s. By 1980, many PCCs had received new coats of paint and necessary mechanical rehabilitation to keep them running for many more years.

Arborway Carhouse in the Early 1980s was tightly packed with PCCs, particularly "Post-War" "Air-Electric" models. As seen in the photograph above, the cars were freshly painted following their rehabilitation and were ready to take on the remaining five years of their operation on the Green Line (or, in the case of at least 3265 pictured above if not more car behind, service until today in Mattapan).

By 1985, the last year of service on the Arborway Line, those PCCs that remained in service in Boston were in deplorable condition. Many PCCs continued to be stored at Arborway Yard into the 1990s to serve in case the Arborway Line was restored and fell into disrepair after being significant vandalized while sitting unattended in the Yard for upwards of five years. Accordingly, the MBTA began scrapping most of its remaining PCCs in the mid 1990s, selling those that were in better condition off to trolley museums across the country.

Former Green Line "All-Electric" PCCs idle in Arborway Yard in 1991, six years after the end of PCC service on the Green Line. As you can see, the cars were stored haphazardly, basically inviting vandals to come and strip the cars of any valuable materials. Accordingly, the photograph above shows the cars in terrible condition—if they were to have been put back into service, the PCCs still at Arborway in the 1990s would have required extensive restorations that would have been possible, yet would have cost the MBTA millions of dollars. Image copyright Plate Dog.

Yet in the meantime, PCCs continued to run in Boston far from the scene of the Green Line, on an oft-overlooked section of the Red Line subway branch, the Mattapan High-Speed Line. Easily mistaken for a continuation of Red Line subway service by the typical peruser of an MBTA map, the Mattapan Line is a trolley line that provides service from the end of the Cambridge-Dorchester subway line, today known as the Red Line, at Ashmont to Mattapan Square (see "Mattapan High-Speed Line" for more information).

Converted to streetcar service from steam trains in 1928, the Mattapan Line has operated continuously since with a variety of streetcar types. Served by PCCs since 1955, the Mattapan Line was served almost exclusively by Dallas PCCs (and a few all-electrics) from 1960 until the retrial of all Dallas PCCs in the late 1970s. Most of the Dallas PCCs that served the Mattapan Line had previously served on the Green Line and accordingly were painted green, but once it became clear they would stay in Mattapan many Dallas PCCs were painted red to represent the Mattapan Line's association with the Red Line.

Converted to streetcar service from steam trains in 1928, the Mattapan Line has operated continuously since with a variety of streetcar types. Served by PCCs since 1955, the Mattapan Line was served almost exclusively by Dallas PCCs (and a few all-electrics) from 1960 until the retrial of all Dallas PCCs in the late 1970s. Most of the Dallas PCCs that served the Mattapan Line had previously served on the Green Line and accordingly were painted green, but once it became clear they would stay in Mattapan many Dallas PCCs were painted red to represent the Mattapan Line's association with the Red Line.

Red-painted Dallas PCC in Mattapan Yard in the 1970s. Note that there is only one trolley pole on the car, which is double-ended—the MBTA converted a number of Dallas PCCs that were assigned to the Mattapan Line to single-ended operation as they would always be able to loop there and having more parts (e.g. trolley poles) would just increase the risk of equipment failure. Image copyright Joe Testagrose.

To this day, PCCs continue to operate on the Mattapan Line, making the Line the longest continuous PCC operation in the country at almost 60 years! All of the PCCs that operate in Mattapan today are "Post-War" PCCs that have been beautifully repainted to match their appearance back when they were run by the MTA along a variety of streetcar lines all over Boston.

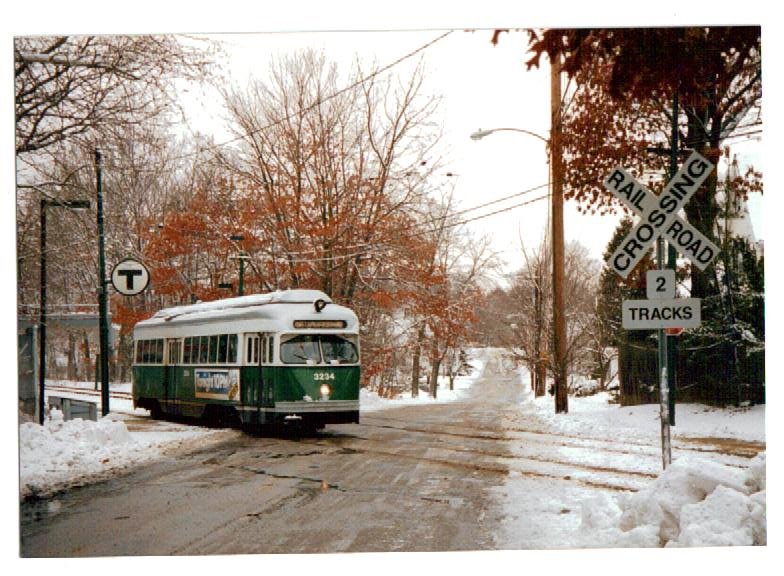

The appearance of Mattapan PCCs prior to their restoration, pictured above by Capen Street Station on the Mattapan Line. The cars were still painted green for years, a remnant of their service on the Green Line. #3234, pictured above, is in especially good shape exterior-wise; many of the other Mattapan PCCs were very rusty and in dire need of a new coat of paint prior to their restoration. Image copyright Panoramio User htabor.

Mattapan PCC #3262 pictured following extensive restoration that was performed on all Mattapan PCCs starting in 1999 and finishing in the mid-2000s. The restoration brought #3262, as well as the entire Mattapan PCC fleet, back to its original 1940s/1950s appearance as a member of the MTA (not BERy, as you will see below) streetcar fleet.

The map logo printed on the side of every Mattapan PCC. The logo is meant to evoke the MTA's map logo, printed on the side of many of its trolleys, and shows the paths of all of Boston's trolley and subway lines around the region.

For contrast, take a look at "All-Electric" #3299 above painted in MTA garb with the map logo on its side.

Image copyright Brooklyn Historic Railway Association.

Image copyright Brooklyn Historic Railway Association.

It is a testament to PCCs proven reliability and pleasurable riding experience that PCCs continue to run in Mattapan today. So many other trolley types, from the over-used and deteriorated Type Fours to the extremely reliable Type Fives to the deplorably unreliable Boeing LRVs, have come and gone in Boston over the past seventy years, yet only one, the PCC, has soldiered on. Having ridden the Mattapan PCCs, I can say firsthand that they are extremely quiet, even more so than the modern day Type Seven and Type Eight cars that run on the Green Line, and that they appear extremely solidly constructed. Perhaps my impression is due to their expertly performed recent restoration, yet the fact alone that trolleys built in the mid-1940s are still running so reliably seventy years later in Boston and along revenue trolley lines across the country is a clear indicator that PCC streetcars were built to last.

Here's to seventy more years of reliable PCC operation in Mattapan and beyond!

Note: to see some photographs of mine of the F-Market Line in San Francisco, a recently restored streetcar line that runs PCCs painted in the schemes of former PCC operations across the country as a tribute to the PCC streetcar's reliability and well-deserved notoriety, read "How A Streetcar Works."

Here's to seventy more years of reliable PCC operation in Mattapan and beyond!

Note: to see some photographs of mine of the F-Market Line in San Francisco, a recently restored streetcar line that runs PCCs painted in the schemes of former PCC operations across the country as a tribute to the PCC streetcar's reliability and well-deserved notoriety, read "How A Streetcar Works."

Type 6 (Mockup)

By the mid-1960s, much of Boston's PCC fleet, the newest of which (All-Electrics) had been built in the early 1950s and most of which dated back to the mid-to-late 1940s, had provided many years of loyal service and was beginning to show its age. It was clear that a replacement for many of the cars would have to be procured sooner than later. The MBTA began its search for a new streetcar by designing its own prototype streetcar that it could potentially produce. In 1968, MBTA engineers at Everett Shops created a mockup for a new streetcar, the "Type 6":

Front view of the Type 6 mockup.

Painted in the gray-and-yellow late-60s MBTA paint scheme and made from wood, the Type 6 resembled a PCC very closely and featured a roomy, well-configured interior with ample space to sit and stand:

Interior of the Type 6 Mockup. Image copyright hopetunnel.org.

The MBTA authorities approved of their engineers' work and were ready to produce the Type 6, but unfortunately the price to mass-produce the mockup proved to be too high. Therefore, the MBTA was left to pursue rolling stock from outside manufacturers.

Walk-around clip of the Type 6 Mockup, which is on store and display to this day at the Seashore Trolley Museum.

Boeing LRV

Boeing LRV on the C Branch of the Green Line in 2000.

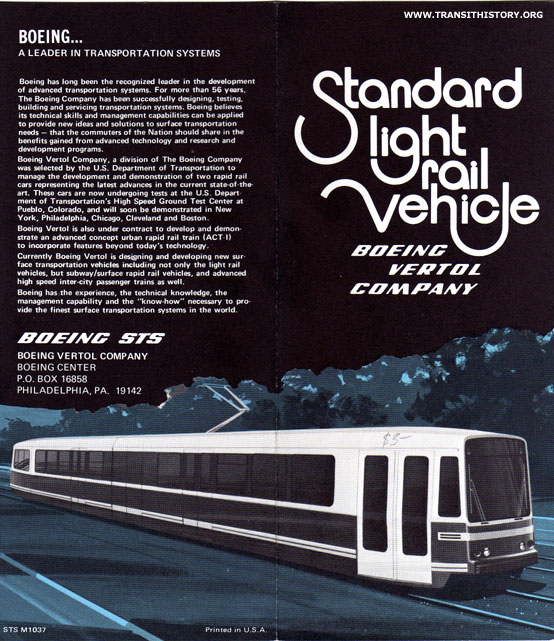

Since producing the Type 6 would be too expensive, the MBTA began searching for a streetcar design that would suit Boston's needs that could be produced and procured at a low cost. At the same time, San Francisco's MUNI was also in the market for a new streetcar. Therefore, the MBTA and MUNI teamed up to design a new streetcar, the U.S. Standard LRV. The design for the streetcar was developed, and in 1973 the contract to build the new cars was awarded to Boeing-Vetrol:

Mid-1970s brochure announcing the design of the new LRV. Note the pantograph on top of the LRV—the Boeing LRVs will be the first streetcars in Boston to use pantographs (more on pantographs vs. trolley poles in "How A Streetcar Works").

LRVs began to be delivered to Boston in 1976. The new cars were considered state-of-the-art in Boston, with sleek, modern styling and first-of-their-kind features such as pantographs. However, the LRVs soon proved to be plagued with problems—among them derailments, unreliable articulation, corrosion and plug doors that had trouble opening and closing. It quickly became clear that the LRVs, at least in their delivered form, were not a good fit for Boston—in addition to their unreliability, having been designed jointly with San Francisco the LRVs included some features, such as plug doors (doors that quickly slide open and shut rather that fold), that were better suited for San Francisco's raised-platform subways than Boston's streetcar infrastructure.

Boeing LRV in 1979 at Reservoir Yard in Brighton—note plug doors and absence of rooftop air conditioning units. For comparison, see snow Boeing LRV photo two photos ago. Image copyright Mike Szilagyi.

As soon as the late 1970s, the LRVs were falling apart—the MBTA was constantly scrambling to keep at least some of the cars in service and had to resort to taking parts from disabled LRVs just to keep some of them running! The LRV turned into a political debacle—major news stories were run in Boston newspapers showing pictures of dozens of disabled, unusable LRVs around the MBTA's system. It quickly became clear that the LRVs would not serve as the long-term PCC replacement they were intended to be.

San Francisco MUNI Boeing LRV—note that the car is identical to the Boston LRVs minus paint scheme.

MUNI LRV at a station in San Francisco—note the raised platforms along MUNI's light rail network, for which plug doors make more sense than folding doors, which fold outward onto the platform.

The MBTA was able to make up for some of its financial losses by successfully suing Boeing-Vetrol in 1979 and earning financial compensation and the termination of its contract with Boeing-Vetrol. Accordingly, some 40 LRVs that were supposed to have been sent to Boston did not make it and ended up being purchased by San Francisco to supplement the LRV fleet there.

New LRVs under construction at Boeing-Vetrol's plant.

Now, Boston was stuck with 135 unreliable LRVs which the MBTA would have to decide what to do with. Many cars were scrapped, as they did not work and were simply a waste of space. Some were sold to San Francisco. Others were repaired using parts from scrapped cars and subsequently pushed into service. By 1983, the MBTA had about 110 active LRVs, including about ten more that it ended up purchasing from Boeing-Vetrol despite the contract termination to provide additional inventory. Many PCCs were also restored at the time, as the MBTA needed additional streetcars and was not yet ready to retire the PCCs, particularly when they were more reliable and better built than the LRVs—by 1987, LRVs were still proving to be problematic, and accordingly the MBTA subsequently began to scrap many of them.

Boeing LRVs stopped at Coolidge Corner Station on the Green Line's C Branch in their last years of service. Note heavy metal corrosion on the chassis; also note the folding doors up ahead that fold outward onto the platform, installed instead of the plug doors in the mid-90s. Compare the folding doors to the plug doors on San Francisco's raised platforms—which folding doors were better suited for Boston, plug doors were better for San Francisco, where folding doors would have likely not been able to open onto the raised platform!

Following extensive restoration, LRVs ended up serving Boston until 2007, by which time they were 31 years old. During the mid-1990s, those LRVs that had not yet been scrapped underwent an extensive overhaul during which significant improvements were made, such as rooftop air conditioning units to replace the undercarriage-mounted units that constantly collected dirt and folding doors to replace the plug doors—now that the MBTA was no longer under contract with Boeing-Vetrol, it was free to modify the LRVs as it wanted to. While most were scrapped by the mid-1990s, a good number of LRVs were restored by the MBTA well enough to continue serving well into the new millennium. To this day, three LRVs remain on MBTA property as work cars, proof that trolleys, while some are made better than others, can last forever if properly maintained.

Photos of the MBTA's three LRV work cars:

New Flyer Trackless

New Flyer trackless trolleys on Mount Auburn Street in Cambridge operating on Routes 71 and 73. Note that the trolley poles of the 73 trackless, which is about to bear right onto Belmont Street, have swiveled to the left to maintain contact with the overhead wires—trackless trolleys' constant lane-weaving is why trackless trolleys cannot use pantographs, as covered in "How A Streetcar Works." Image copyright hopetunnel.org.

By the 1970s, Boston's Pullman and Brill trackless trolleys were beginning to show their age. Many were heavily corroded after +-30 years of service, and it was time to procure a replacement.

Pullman trackless trolley around 1970. Note corrosion of chassis as well as left-side door—Boston trackless trolleys require left-hand doors so they can stop at the Harvard Bus Tunnel's left-side platform. Also note maroon BERy number strip and cream-and-orange paint scheme—this trackless has been through three transit agencies, serving Boston since the 1940s!

In 1976, the MBTA accepted an order of fifty trackless trolleys from New Flyer, allowing the Pullmans and Brills to be retired. Now that there were only four trackless trolley lines remaining in Boston, the MBTA required many fewer trackless trolleys to maintain service! The new trolleys featured left-hand doors and served Boston until 2008, for 32 years. These trolleys proved to be very reliable and would have lasted longer had it not been necessary for the MBTA to procure new low-floor trackless trolleys to meet new ADA federal accessibility requirements.

Note: In 1950, the MTA's trackless trolley inventory stood at 725 trolleys! [Source for Number: http://www.trolleybuses.net/bos/bos.htm] More on the history of Boston's trackless trolley operations at "Trackless Trolleys.")

New Flyer trackless trolley #4037 at North Cambridge Carhouse shortly before retrial. #4037 still exists today at the Shore Line Trolley Museum in Connecticut! Image copyright Flickr User bradlee9119.

Type Seven & 7.5

Type 7.5 at Science Park Station on the Lechmere Viaduct, the last elevated train structure remaining in Boston since the demolition of the Causeway Street Elevated in 2004, in 2006, when the Northpoint residential development in East Cambridge (construction up ahead) was still under construction and Science Park Station was just about to undergo significant renovations. Note the black rollsign on the streetcar—when I took this picture, the MBTA was just beginning to convert all Type 7 and Type 7.5 streetcars to be compatible with the then-new Type 8 streetcars. Today, all Type 7s and Type 7.5s have been outfitted with digital LED destination signs like those on the Type 8s and run in trains with them regularly. Image copyright Me (Gil Propp).

By the early 1980s, with the Boeing LRVs proving to be very unreliable and the PCCs still in service in dire need of restoration, the MBTA was in dire need of new, reliable streetcars. After its less-than-ideal experience with the Boeing LRVs, the MBTA decided that with its next streetcar, it would start from scratch and design a streetcar that would best serve the its needs and not repeat the problems found with the Boeing LRVs.

Boeing LRVs by Eliot Station on the Riverside Line in Newton in 1977, a year after their arrival in Boston. The LRV train pictured above is retrofitted with the plug doors that were notoriously unreliable and caused a significant nuisance for the MBTA, just one of many reliability issues with the Boeing LRVs.

The MBTA came up with a design and commissioned Japanese engineering firm Kinki-Sharyo to build a new LRV for Boston. A total of 100 new cars, numbered 3600-3699, were ordered from Kinki, beginning in 1986 and ending in 1987. The new design quickly won favor in Boston, as it was wide and roomy not to mention that its design evoked the PCCs, which by now had reliably served Boston for +- forty years.

Pair of Type 7 LRVs at Packard's Corner in Allston on the B Branch of the Green Line, painted in their original green-and-white paint scheme. Note that the front end closely resembles a PCC; also note accordion articulation at the center of the cars. Image copyright Peter Kingman.

Like Boston's PCCs, the Type 7s have since proven to be very reliable assets for Boston. The cars are very dependable and are much better built than Boeing's LRVs—the cars shown above were pictured in 2003, 16 years after their delivery to Boston, and still appear strong and solidly constructed without having received any major rebuild. In particular, the cars' articulation is much better built than that of the Boeing LRVs, and accordingly Type 7s have had almost no major derailments (not caused by operator error), allowing them to be used on lines, such as the E Branch of the Green Line, with sharp, street-running curves. Accordingly, the MBTA has been very pleased with Kinki's work on the Type 7s, opting to order 20 more in 1997 (Type 7.5s) despite the design being ten years old. Likewise, in the late 2000s, when the cars were reaching their twentieth year in service, the MBTA opted to install digital display signs, electronic stop announcements, new couplers and new wheels in all Type 7s to make Type 7s mechanically compatible with the MBTA's new Type 8 streetcars.

Green Line trolleys at Heath Street Loop. Trolley in foreground in #3709, a Type 7.5. Up ahead is a Type 7 repainted in the new Green Line paint scheme. Connected to #3709 is a Type 8; all Type 7s and Type 7.5s have been made mechanically compatible with Type 8s.

Type 7 Kinki LRV #3611, exterior and interior. As you can see, #3611, originally painted in the original dark green and white scheme shown earlier, has been repainted into the more recent light green and steel scheme. Circled in red is the new digital destination sign, and circled in blue is the new digital stop announcement sign. Circled in red is the where a manual destination sign was once inserted on Type 7s—note that the sign now holds a digital destination sign visible from the outside. Image copyright Kinki-Sharyo.

Type Eight

Type Eight streetcar #3894 leaving Brookline Hills Station for Riverside during the legendary Blizzard of 2013. Image copyright Me (Gil Propp).

With the Boeing LRVs clearly not a long-term solution and a planned future Green Line Extension to Somerville and Medford, the MBTA still had to procure some additional new streetcars. Also, with Type 7 trolleys requiring outside ramps for people with disabilities to board, it was clear that more-easily accessible streetcars would have to be bought. Therefore, the MBTA turned to Italian engineering firm AnsaldoBreda to design and build new accessible trolleys, the Type 8s. The first Type 8s began arriving in Boston in 1998, a year after the Type 7.5s:

Initial Type 8 prototype, #3800, upon delivery to Boston. Image courtesy Flickr User mbernero.

Initially, the Type 8s were plagued with problems. From brake problems to derailments, the Bredas were proving to be similar to the Boeings in reliability—the MBTA was constantly reassigning Bredas to different branches of the Green Line after it was proven that the Type 8s could not operate on different branches due to their wheels being unfit for existing trackage. Accordingly, in 2004 the MBTA declared it was halting its contract with Breda after receiving only 47 Type 8s. The MBTA proceeded to modify the Type 8s it had received so that they could operate on the MBTA's tracks and succeeded, reinstating its contract with Breda a year later and proceeding to receive a total of 95 Type 8s. The MBTA has since made significant modifications to Green Line trackage to accommodate the Type 8s and swapped wheels on all Type 7s to bring them in line with the Type 8s, ensuring that Type 8s will serve the Green Line for years to come.

Type 8 #3855 with a modified Type 7 behind it at Reservoir Yard in Brighton. Type 8s are now run regularly with Type 7s pulling or trailing them, ensuring there is one accessible streetcar per Green Line train.

Neoplan Trackless

Neoplan tracklesses in Waverley Square in Belmont along Route 73. Image copyright Me (Gil Propp).

By the late 1990s, the MBTA's New Flyer trackless trolleys were beginning to show their age. Chassises were corroded, not to mention that the trolleys, which had been running since the 1970s, were beginning to look faded and out-of-date in comparison to new RTS buses. Therefore, the MBTA sought to procure 28 new trackless trolleys to replace the New Flyers. Neoplan, then a leading bus manufacturer, was chosen to build the new tracklesses. The new tracklesses would be ADA-compliant and would, like the Flyers before them, feature a left-hand door to use in the Harvard Bus Tunnel and along Aberdeen Avenue on Route 72.

Neoplan trackless #4106 operating in the Harvard Bus Tunnel on Route 73. As you can see, the platform is on the left side of the tunnel, dating back to when the tunnel was used by streetcars. Therefore, trackless trolleys that are to be used in the tunnel require a left-hand door.

Image copyright Flickr User ck4049.

Image copyright Flickr User ck4049.

Aberdeen Avenue in Cambridge, along Route 72, one of four trackless trolley routes remaining in Boston (71, 72, 73 and 77A). As you can see by the bus stop sign on the median, bus stops on Aberdeen Avenue are located in the center of the street as they have been since Route 72 was a streetcar line, requiring a left-land door to serve the route. Also note that the double trackless trolley wires here are mounted in the center of the street, a unique feature dating back to streetcars.

When Neoplan's initial mockup, #4101, arrived in Boston, it was noted that Neoplan had forgotten to include a left-hand door. This caused a commotion—after inquiry by the MBTA, Neoplan claimed that it would be impossible to include a left-hand door on the new trolleys without spending a significant chunk of money. At the same time, the MBTA had also ordered 32 Dual-Mode trackless trolleys from Neoplan for use on the then-new Silver Line, which were proving to be very hard to engineer and were also a point of contention between the MBTA and Neoplan at the time. The MBTA continued to press Neoplan for a left-hand door and for dual-mode tracklesses and ultimately won, sending Neoplan to bankruptcy in the process. Ultimately, Boston got 28 solidly-constructed new trackless trolleys with left-hand doors and 32 additional trolleys for the Silver Line.

#4107 at North Cambridge Carhouse, complete with a left-hand door. Image copyright Flickr User ck4049.

Silver Line dual-mode trackless #1129 along the Silver Line's South Boston Transitway. As indicated by their name, these tracklesses can run on electricity or diesel—electricity is used in the underground Transitway, and diesel is used on the street-level section of the Silver Line in South Boston and when traveling to Logan Airport. Image copyright Malcolm McCrow.

Silver Line dual-mode trackless #1115 in the South Boston Transitway. Note that the dual-modes do not have left-hand doors.

Image courtesy Flickr User Utahbeach.

Image courtesy Flickr User Utahbeach.

While the dual-mode tracklesses, which arrived in Boston in 2006, were being built, the MBTA used 12 of its trackless trolleys procured for the Cambridge lines, which arrived in 2004, in the South Boston Transitway as show above. The tracklesses were wrapped in Silver Line colors and operated along the transitway until the dual-modes arrived, keeping New Flyers in service in Cambridge a few years longer than they likely would have been kept otherwise. Image copyright Jonathan Wiggs.

Type Nine

Rendering sketch of possible Type 9 Green Line streetcar. Image copyright MassDOT.

Now that the MBTA is extending the Green Line northward past Lechmere to Somerville and Medford, additional Green Line streetcars will need to be procured to accommodate the increase in service. Accordingly, the MBTA is currently seeking to design and procure 24 new Green Line streetcars. The new cars will be fully ADA-compliant and will be mechanically compatible with Type 7s and Type 8s. At the moment, there are many possible designs for the cars, which can be found at http://greenlineextension.eot.state.ma.us/documents/about/Topics/GrnLnType9Veh_ConceptDrawings.pdf. As work on the Green Line Extension progresses, it is likely that Type 9s will arrive in Boston in due course.